Portrait of John Stuart, 19th c. copy of an alleged original.

(Source: base de données Joconde).

One peculiar aspect of the "auld alliance" between France and Scotland (founded on the common enmity with England) was the existence of French titles held by Scots nobles. These notes discuss three known cases: the earls of Douglas, the Stuarts of Darnley and the earl of Arran. They also discuss the case of another Scottish family which was granted a quarter of France in their arms, namely and Kennedy. Finally, the case of Montgomerie is discussed because their arms, by coincidence, were identical with those of France.

See also The Great Hall of the Clans for more information on Scots clans and heraldry.

1415 had been a bad year for France: the army of Henry V of England defeated the French at Agincourt (Azincourt in French) and the French nobility was decimated. English troops occupied Northern France, and the treaty of Troyes (1420) was imposed on the mad king Charles VI and his divided court. The treaty provided for the marriage of Henry V with Charles VI's daughter, and the accession of Henry V to the French throne upon the death of Charles VI, passing over the Dauphin Charles, son of Charles VI.

Earlier, in June 1419, the Dauphin had escaped Paris and taken refuge in Bourges. There, he summoned the Scots to his help, and a contingent of soldiers arrived from Scotland, led by the duke of Albany, the earl of Douglas and Sir John Stuart, lord of Darnley. For the next 5 years, these Scottish soldiers provided crucial support to the Dauphin, who assumed the name of Charles VII on the death of his father in 1422. They allowed the party of Charles VII to resist the English, until fortune changed sides with the counter-offensive led by Joan of Arc in 1429-31. In particular, a stunning victory was achieved at Baugé in 1421, during which the duke of Clarence, brother of the English king, was killed. The Scottish troops were badly defeated at Verneuil in 1424, and again trying to relieve the besieged town of Orléans in 1429. Orléans was relieved by Joan of Arc, and Paris and Normandy were retaken in 1436. The remnants of this Scottish force remained in the service of the king of France, were reorganized as the Gardes Écossaises when a permanent French army was formed in 1475, and remained the premier corps of the King's Household Troops until the Revolution. The captainship of these troops remained hereditary in the Stuart of Darnley family until the 17th c.

One of the leaders of the Scottish expeditionary force was Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas (called Archambault Douglas in French texts). Obviously, Charles VII had little money with which to reward his supporters, although his supporters were few. One way to express his gratitude was to bestow honors; and giving fiefs was a way to help them support the costs of war far from home.

The earl of Douglas was made Constable of France in 1421. By Letters Patent of April 19, 1424, he was given the duchy of Touraine to hold in peerage by him and his heirs male of the body (Père Anselme 3:231), and gave homage the same day. The earl was killed at the battle of Verneuil on August 17, 1424. His only son Archibald, who had been made count of Longueville, succeeded as 5th earl of Douglas; he had left France for Scotland in 1423, and at the time of his father's death a rumor reached France that he had died without children; the king assumed the title extinct and gave the duchy to Louis d'Anjou on Nov. 21, 1424. When the news were disproved, the 5th earl was allowed to retain the title of duke of Touraine (Dictionary of National Biography, s.v. Archibald Douglas, Père Anselme, 3:231). He died in 1439. His only two sons, William and David, were executed for treason in 1440 in Edinburgh and the descent of the 4th earl was extinct.

The 4th earl of Douglas used two arms on his seals: one was Quarterly Douglas and Galloway, en surtout Murray of Rothwell (Stevenson and Wood), another was Quarterly Douglas, Galloway, Murray and Annandale (Catalogue of Seals, 16054). One seal, attributed to him, shows a modified version: Quarterly France, Douglas, Annandale, Galloway with the title of duke of Touraine, earl of Douglas and of Longueville in the legend. However, both Laing (suppl. 282) and the catalogue of the British Museum (16055) date it to 1421, which is impossible; moreover, the title of count of Longueville was given to the 4th earl's son. I suspect that the latter seal belonged to Archibald, 5th earl. In any event, the 4th earl did use those arms with a French quarter, since a seal of his widow Margret, daughter of Robert III king of Scots, shows Quarterly France, Douglas, Annandale, Galloway impaling Scotland, and the title of duchess of Touraine (on a document dated 1425; Laing).

Both the 5th and 6th earls used the same shield with a quarter of France and the title of duke of Touraine (Stevenson and Wood). No other earl of Douglas did so.

It is not clear where the escutcheon comes from. This was the first time that a French king conferred a peerage on someone who was not of royal blood. Hitherto, the differenced arms of France became associated with the peerage, so that the arms of Touraine, Burgundy modern, Anjou, Berry, Alençon, as provinces, are all differenced versions of the arms of France. In other words, there were no arms of Touraine proper to be borne by a non-royal.

Although there is no evidence to that effect, I suspect that the reason for the escutcheon is the same as that for the escutcheon of the Stuarts of Darnley, which is well documented, and for the quarter of the Kennedy of Bargany. Thus, the escutcheon of France is not a mark of peerage, and does not represent the duchy of Touraine (or the seigneurie of Aubigny in the case of the Darnley), but a special augmentation conferred by the king independently of any fief.

Another Scottish officer was Sir John Stuart, lord of Darnley (See Cust for a full account of the Stuarts of Aubigny). member of a junior branch of the house of Stuart, which had since become royal, was born ca. 1365. After the battle of /Baugé, he was given the lordship of Concressault in Berry (30 mi north of Bourges), and later, on 26 March 1424, the nearby lordship of Aubigny-sur-Nère to him and his heirs male of the body (Père Anselme 5:921; other sources such as the court rulings of 1839 discussed below give the year as 1422). Aubigny, given by its lords in 1080 to the chapter of Saint-Martin of Tours, was bought by the king of France in 1180, and given in apanage twice before; it had returned to the crown in 1416 on the death of the duc de Berry). As was customary with grants of royal estates, Aubigny was to return to the crown upon extinction of the male line of the grantee. Then, by Letters Patent of January 1428, he received the county of Évreux. The text of the letters patent do not indicate that it was given in peerage (Père Anselme 3:98). Furthermore, a deed of March 15, 1427, signed by Darnley, gives the king the option to buy back the county for 50,000 crowns in gold (Cust).

In February 1428, letters patent gave to Sir John Stuart of Darnley, count of Évreux, the right to "bear forever in his arms, escutcheons of France, that is to say, in the first and last quarter thereof in each 3 flowers de lys of gold in a field azure, so and in such form as the same is here portrayed, depicted and blazoned. Willing and granting that this our present gift, grace and grant may by him and his descendants who ought to bear his said arms be enjoyed and used from time to time forever." (Cust).

John Stuart of Darnley was killed in battle on Feb 9, 1429, trying to relieve Orléans. His eldest son Alan inherited the lands in Scotland, and his second son John inherited Aubigny and Concressault (it is not clear when Évreux was returned to the king, but none of his descendants ever used the title; in any event, Évreux was still in the hands of the English at the time). John gave homage for Concressaut in 1461, but in 1487 we then find that lordship in the hands of Alexander of Menypeny, to whom it had probably been sold.

The descendants of Alan, who became earls of Lennox, remained in close contact with the Aubigny branch, which included: John († 1482), his son Bérault († 1508) who gave homage for Aubigny in 1483, and Bérault's daughter Anne who married her cousin Robert Stuart, grandson of Alan († 1543): Anne and Robert gave homage for Aubigny in 1508. Aubigny then went to another younger son of the elder branch, John Stuart († 1567), who gave homage in 1560, whose son Esme († 1583) was made earl of Lennox in 1580 and 1st duke of Lennox in 1581. The successive lords of Aubigny dutifully swore liege homage to the king of France (in 1600 by Esme, son of the 1st duke of Lennox, in 1636 by George Stuart, in 1656 by Ludovic Stuart, in 1670 by Charles Stuart).

Meanwhile, the elder branch had ended with Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, husband of Mary Queen of Scots, and father of James VI (I of England); thus, when the 6th duke of Lennox and 11th seigneur d'Aubigny died in 1672, the heir to Aubigny was the king of England and Scotland, Charles II. Louis XIV, however, was reticent to have a foreign sovereign own fiefs in France, and refused to acknowledge the inheritance, and an arrêt du conseil of 20 Jan 1673 pronounced the reversion of Aubigny to the crown. But he accepted to give the fief of Aubigny to Charles II's mistress Louise-Renée-Renée de Kéroualle, duchess of Portsmouth, with reversion to an illegitimate son of hers, of Charles II's choosing, and his heirs males (Dec 1673). By Letters Patent of Jan 1684, the fief of Aubigny was created a duchy-peerage, with the same terms. But the letters patent were not registered until in the parliament of Paris (Père Anselme, 5:929). The fact that the Parliament had not registered the letters is apparent in the liege homage given to the king of France by Louise de Kéroualle in 1684 and her grandson Charles in 1734: the gave homage for the "seigneurie" or "terre et châtellenie d'Aubigny", not for the duchy. The lordship was sequestered during the War of Spanish Succession but returned to its owner pursuant to the treaty of Utrecht in 1713. On the duchess of Portsmouth's death in 1734 the lordship passed to her grandson the second duke of Lennox and Richmond. The peerage became extinct with her death, since the letters patent were not registereed within the customary one year delay. On June 29, 1777, Louis XVI issued "lettres de surannation" which in effect gave force again to the original letters patent; the Parlement registered on July 1, 1777, and the peerage was restored and made hereditary (Christophe Levantal, Ducs et Pairs..., p. 267).

An interesting legal case developped around Aubigny in the 19th c. (see reports in Recueil Dalloz 1840, p. 245; Recueil Sirey, 1839, I:577, 1840, I:266). In 1792, the estate was again sequestered, and later returned to its owner, the 3d duke, after the peace of Amiens in 1803. Sequestered once more when war broke out again, it was confiscated as property of a British subject by the decree of 21 November 1806. The same year, the 3d duke died, leaving three sisters and a nephew, the 4th duke.

Article 4 of the additional clauses of the treaty of Paris of 30 May 1814 called for the return of all sequestered property; a separate, secret and unpublished clause, specified that "the sequester on the duchy of Aubigny and its appurtenances shall be removed, and the duke of Richmond shall be given possession of these estates in their present state." A royal ordonnance of July 8, 1814 and an arrêt of the prefect of the Cher department of August 3 ordered this to be done. On 30 Nov 1814, the 4th duke recovered his property. He was even given an indemnity for the portions of the estates that had been sold and for the foregone income. He died in 1819, and his son the 5th duke inherited Aubigny alone.

The duke of Richmond faced one difficulty. A law of 14 ventôse 7 (1799) had decided that owners of property subject to a reversion clause to the crown had to pay 1/4 of the value of their property in order to retain full ownership. The duke claimed to be exempt of that law, but the courts ruled against him (court of Sancerre, 1836; appeals court of Bourges, 1837; Court of Cassation, 1840).

In 1834, however, the sisters of the 3d duke sued: under post-Revolutionary French law, the estate should have been shared at the death of the 3d duke between all heirs equally. The sisters demanded 4/5 of the estate. The duke argued that the clause of the treaty of 1814 created an exception to that law in his favor, and that the courts were incompetent to interpret or alter an international treaty. He lost in the court of Sancerre in 1834, but won on appeal to the court of Bourges in 1835. The Court of Cassation overturned on 24 June 1839, saying that there was no reason to suppose that the said clause was intended to create such an exception to general French law.

The Stuarts of Darnley took advantage of the honor bestowed upon their ancestor. John Stuart of Darnley used to bear Or, on a fess chequy argent and azure a bend sable. There is no evidence on the arms he bore after the grants were made to him, but his son Alan bore Quarterly Stuart and France. Bérault Stuart of Aubigny bore Quarterly France on a bordure gules 8 buckles or, and Stuart, while the first four earls of Lennox (from 1470 to 1571) used Quarterly: France, and Stuart on a bordure gules 8 (sometimes 10 or 12) buckles or, en surtout Lennox (argent a saltire between four roses gules). The heir and grandson of the 4th earl being James VI of Scotland, the title went to a younger son of the 4th earl, and then a younger brother. With this 6th earl, the bordure with buckles is now in the French quarter and replaced by a bordure engrailed gules in the Stuart quarter (Stuart-Darnley). The 7th earl of Lennox becomes duke of Lennox in 1581, and the 1st, 2d and 5th dukes use the same arms. Also, starting in 1579, the saltire of Lennox is engrailed. But the 2d, 4th and 6th dukes place the bordure engrailed on the French or the Stuart quarter (Stevenson and Wood, Catalogue of Seals).

The dukes of Aubigny place an escutcheon bearing Gules three buckles or to stand in for Aubigny, although the buckles in fact come from John Stuart of Bonkyl († 1298), ancestor of the Stuarts of Darnley.

In Heraldic Marylandiana (1968) , Harry Wright Newman tells the story of Alexander Stuart, son of Sir Alexander Stuart, born in 1718; a Jacobite, he went to France where he was given on June 10, 1738 the barony of "Stuart d'Aubigny", on account of his being descended from Alexander, son of the earl of Lennox. He later moved to Annapolis, MD where he settled. The title was supposedly confirmed in 1885 by the French government, and the current holder is Donald Franklin Stewart, of Baltimore, MD.

Perhaps the descent is from Alexander († before 1508), 3d son of John Stuart of Darnley, 1st earl of Lennox. In any event, I find the story rather dubious, but here it is.

This last case is rather interesting, because the heraldic consequences last to this day (see Cockaygne vol.1 appendix B, and Stodart for a near-full account).

James Hamilton, 2nd earl of Arran, was regent of Scotland during the minority of Mary Queen of Scots (he was in fact heir presumptive, being her second cousin through his grandmother, and next in line for the throne). Immediately, here were two main contenders for her hand: Henry VIII's eldest son the prince of Wales, and Henri II's eldest son François Dauphin of France. The earl, as regent, was the kingpin: he was finally persuaded by the French to sign a treaty with them for the marriage of François and Mary. The earl even went so far as to convert to Catholicism. His price was spelled out in the treaty of Châtillon (27 Jan 1548), which promised "to confer the title of duke, with a duchy in the kingdom of France of 12,000 livres of revenue, for him and his heirs." The deed was made by letters patent of 8 Feb 1549 (Père Anselme 5:586), which gave the duchy of Châtellerault with all its revenues and fees, "which we guarantee to the amount of 12,000 livres per year of revenue". In other words, the main point was a title and a guaranteed income, which the king of France promised to top off if it fell short of the promised amount. Note that the duchy was not held in peerage, but that the remainder included all heirs (unless specified otherwise, that meant male as well as female). The letters were registered on 2 Apr 1549. (A vidimus of 13 May 1556 exists in the Archives Départementales, Poitiers, France; it was recently exhibited at the Musée de l'Histoire de France (Oct. 1995 - Jan 1996), Sterling castle, Scotland (Feb - Jun 1996) and the townhall of Aubigny-sur-Nère (Jun - Sep. 1996).) The earl of Arran also received lettres de naturalitß in July 1548, registered in the Chambre des Comptes on 25 April 1549 (Catalogue des Actes de Henri II, 2:319).

In 1559 the duke of Châtellerault returned to Protestantism and turned against his Queen; as a result, his French lands and estates were confiscated for treason in July 1559 (Calendar of State Papers, 3:393). The treaty of Edinburgh between Scotland and England (7 Jul 1560) included a promise that the duke of Châtellerault would be returned to the possession and enjoyment of all the lands he possessed before that date. It seems, however, that things did not follow through. As it turned out, the young François II, king at the death of his father in 1559, died in December 1560, Mary returned to Scotland and no one was much in a hurry to make good on the promise. The duchy was given in 1563 to Diane (d. 1619), legitimated daughter of Henri II, duchess of Montmorency, who exchanged it back in 1582 (Anselme 1:136, 5:602). It was then given to the duc de Montpensier, royal prince of the Bourbon line (26 Nov 1583). The earl of Arran spent a lot of time trying to regain the revenues of his duchy, but his efforts were rebuked: once, during an interview with the king of France, his attempt to bring up the topic of the duchy was abruptly cut short. All he obtained from the king of France was a pension of 4,000 F "in recompense for the duchy" in 1565 (Calendar of State Papers, 8:295, 319).

The 2nd earl of Arran used the title of duke of Châtellerault on his seals, as did his wife (Laing, Catalogue of the British Museum), but it is noteworthy that he did not modify his arms on that occasion. He bore Quarterly Arran and Hamilton in 1549, but Quarterly Hamilton and Arran after 1552. A seal on a document of that year shows these arms with the French ducal coronet and the collar of the French order of Saint-Michel, and the title "dux castri hiraldis" in the legend.

The 2nd earl died in 1575. None of his male descendants ever used the title of duke of Châtellerault on their seals, and they all used Quarterly Hamilton and Arran: the 3d earl, the 1st and 2d marquesses of Hamilton, the 1st duke and the duchess of Hamilton after whom the name and arms passed to the family of Douglas (Stevenson and Wood). But the successors remained interested in the revenue which had been promised in 1548, and pressed the case repeatedly, as he had done himself. Finally, a "brevet" of 4 Oct 1616 from Louis XIII of France granted an annual sum of 12,000 livres to them as compensation for the duchy. It seems, however, that the marquis of Hamilton was harbouring hopes of restoring his ducal title, judging by a letter of Sir Richard Browne, English ambassador to France, dated Jan 13-23, 1643: "I have seen letters lately written from a person of great quality in Sctoland, bearing the Earl of Laudian's speedy coming over hither with his Majesty's leave to treat the renewing of the ancient alliances between the crowns of Scotland and France; upon which treaty many particular interests depend, as, the reestablishing the marquis Hamilton in the duchy of Chatellerault, or the marquis Douglas in that of Touraine" (cited in John Evelyn: Diary, 1854: vol. 4, p. 337).

James (1606-1649), 1st duke of Hamilton and great-grandson of the 2nd earl of Arran, was succeeded by his brother William (1636-51), who left a daughter Ann (1634-1716), heir of the line, duchess in her own right. She had married William Douglas, and Letters Patent of 1643 extended the title of duke of Hamilton to their heirs (and made him duke of Hamilton for life). About that time, the payment of the pension was discontinued, probably on account of uncertainties over the succession. Her son James, 4th duke of Hamilton, pressed again his claims, and a provision of the 1713 treaty of Utrecht (art. 22) contained a promise by the king of France to "satisfy the claims of the family of Hamilton concerning the duchy of Châtellerault". This was done in 1714, by way of giving the duke 500,000 livres in 4% bonds. Unfortunately for the duke, these bonds were reimbursed in 1719 along with the whole French public debt in the form of banknotes which soon depreciated. During the liquidation of 1722, the banknotes were made exchangeable against new bonds, at a drastically reduced face value. The duke refused to agree to the exchange, and matters rested there.

What had happened to the duchy itself? From 1584, it was in the house of Montpensier: the only daughter of the grantee married Gaston d'Orléans and died in 1627 when giving birth to her only daughter, the Grande Mademoiselle, Anne-Marie d'Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier, who also inherited Châtellerault. She died without heirs in 1695, and left her estates to her cousin Philippe d'Orléans, who thus inherited the duchy (though not the peerage or the title). He sold it in the 1720s to Frédéric-Guillaume de La Tremoïlle, whose son Anne-Frédéric was created duke of Châtellerault in 1730; the same died in 1759 without surviving children and the title became extinct again, while the estate went to the heirs, another branch of the La Tremoïlle family.

When Douglas, 8th duke of Hamilton, died in 1799, he left a sister Elizabeth countess of Derby, heir to the line, and his uncle Archibald became 9th duke of Hamilton. It appears that the dukes of Hamilton made their claim to the title of duke of Châtellerault as of the early 19th c., although they were neither heirs general nor heirs male. The earliest evidence for this claim that I have found is in the 1812 edition of Collins' Peerage and the 1814 edition of Debrett's Peerage, which both cite the title of duke of Châtellerault in their entry on Hamilton. The 1844 edition of the Annuaire de la Noblesse de France mentions that the duke of Hamilton was received at the court of Charles X "under the title of duc de Châtellerault" (in 1826, according to the memorandum in support of the Hamilton claims). Burke's General Armory of 1844 blazons the arms of Hamilton with an inescutcheon bearing France in point of honor.

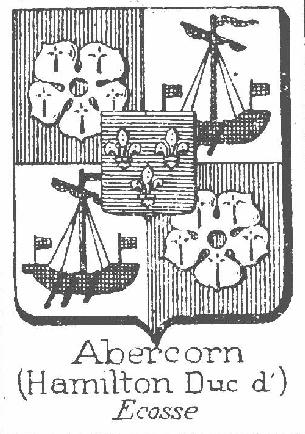

About that time, another character comes into the picture, namely James, 3d marquess of Abercorn (1811-85), descended from Claude Hamilton, lord Paisley, 5th son of the earl of Arran. Claude's son James became the first earl of Abercorn in 1606. His arms were those of Hamilton-Arran differenced with a label or, although the label was dropped when the senior male line of Hamilton died out in 1651. His arms were so entered in the Lords' Entries in 1737. His direct descendant the marquess of Abercorn was heir to the male line of Hamilton, descended from the earl of Arran. As such, he was the first to assert his right to the duchy of Châtellerault: the earliest mention of Abercorn's claim to the title that I have found is in the 1844 edition of the Annuaire de la Noblesse de France. As of 1861, he had not yet used the title (Burke's Peerage, 1861). But on 13 Jan 1862, according to Burke's Peerage, the 2d marquess of Abercorn (who became duke in 1868) upon his request "was served heir male of the body of the first duke of Châtellerault by the Sheriff of Chancery in Scotland, and, as heir male of the first duke, asserted his hereditary right to the original title of duke of Châtellerault of 1549. By Edict of Louis XIV, may 1711, the descent of French dukedoms was declared to be to heirs descendus de mâle en mâle."

This last statement from Burke is incorrect: the edict of May 1711 did not apply retroactively, so that the succession of 1651 could not be undone.

The 12th duke of Hamilton happened to be third cousin of the French emperor Napoleon III through his mother, Mary-Caroline of Baden. While he was a minor, she made a request for confirmation of the title in favor of her son on March 12, 1864; the request, supported by a lengthy memorandum written by the France's head archivist, was considered by the "conseil des sceaux" and approved by the Emperor by decree of April 20, 1864 (published on Aug. 25): "The duke of Hamilton has been maintained and confirmed by decree of Apr 20, 1864 in the hereditary title of duc de Châtellerault created by the king of France Henri II in 1548 (old style) in favor of James Hamilton, earl of Arran." Note that the text is rather strange: it is not a creation, but a confirmation of an existing title (the Almanach de Gotha calls it a new creation by way of confirmation!), in spite of the fact that the original title was hereditary through males and females, and that the duke of Hamilton was not heir to the general line, and could not be confirmed in a title he could not claim.

The marquess of Abercorn, heir to the male line, appealed the decree before the French Conseil d'État, initially asking it to recognize his right to the title and annul the decree, and later admitting that the Conseil d'État could not adjudicate the dispute, but could suspend the decree until civil courts had decided the matter (consultation of 1865, first brief and second brief filed with the Conseil d'État). The Conseil d'État rejected the request on 11 Aug 1866. Civil courts were competent only when the matter at hand was merely a question of applying a decree of creation or confirmation. More substantial disputes belonged to the Conseil des sceaux and the Sovereign. In this instance, there was clear doubt as to the existence and transmission of the title. The advocate for the government recalled the confiscation of 1559 and the transfer of the title to the Montpensier family, and the fact that the French sovereigns never accepted the Hamilton family's requests for the title and never returned it. Civil courts would have sent the case to the Conseil des sceaux, but the decree of April 20, 1864 represented exactly the conseil's decision. The marquess of Abercorn claimed that the decree of 1864 confirmed the title for the whole family of Hamilton, and separately bestowed it to the duke of Hamilton, and disputed the latter but accepted the former. The advocate rejected that interpretation: He then explained: "We do not know what is the recognition and maintainance of a title in abstracto, separated from the individual to whom it is granted. the title had to be maintained and confirmed because there was a possible doubt on its existence, and I have recalled the serious reasons which could have led to doubt the transmission of this title to the heirs of the earl of Arran. The Emperor, in the exercise of his sovereign power, has found it appropriate to return it to the Hamilton family and to erase the traces of the confiscation made three centuries ago. We do not have to determine whether he granted this favor to the one who would have received the title of his ancestors had the transmission taken place in a regular fashion. It appears evident to us that the Emperor has decided within the limits of the power he has by virtue of special law on nobiliary titles" (11 August 1866).

Nevertheless, the marquess of Abercorn (who became duke in 1868) assumed an inescutcheon bearing France and crowned with a French ducal crown on his arms.

The 12th duke of Hamilton died in 1895, leaving only a daughter (married to the duke of Montrose, whence issue). He was succeeded by a distant cousin Alfred, descended from the 4th duke, who claimed the title of Châtellerault, as have his successors since. Whether the 1864 decree was a creation or a confirmation to a specific individual, then one must wonder what the terms of succession were: either succession was to males only (as was the case for the vast majority of 18th and 19th century French titles) in which case the title was extinct in 1895, or else it was to males and females as the 1548 title had been, in which case the duke of Montrose was the heir. In either case, neither Abercorn nor Hamilton could claim the title. Moreover, the Conseil d'État accepted the argument that the title was not recreated in abstracto in the Hamilton family, and it cannot be argued that the 1864 decree implied remainders to the heirs of the 1st duke of Hamilton or to the heirs of the 2nd earl of Arran. Transmission to anyone but the heirs of the 12th duke is very doubtful, in the absence of another decision of the conseil des sceaux. Indeed, Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon, in his Scots Peerage, mentions the confirmation of 1864 for the 12th duke, but adds that the 13th duke "claims the dukedom of Chatellerault", expressing strong doubts on the validity of the claim.

To this day, both dukes of Hamilton and Abercorn continue to claim the title of duc de Châtellerault.

The arguments put forward by the duke of Hamilton in 1863, the decision by the Conseil du sceau, the arguments of the marquess of Abercorn, and the final decision, can be found here (in French).

What about heraldry? As we saw, the duchy of Châtellerault occasioned no change in the arms of the 2nd earl of Arran or any of his male heirs. In particular, he bore the title and placed a French ducal coronet over his arms, but did not include any quarter or escutcheon for his new title. His heirs used the paternal arms but not the title or coronet. In the 19th century, as the duke of Hamilton and the marquess of Abercorn make their claims, they take it upon themselves to change their arms. Burke's General Armory (1844 ed.), Lodge's Peerage (1849 ed.), Burke's Peerage of 1861 show an escutcheon born by the duke of Hamilton en surtout, bearing France and a French ducal coronet (this is prior to the decree of Napoleon III).

Interestingly, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is a room where the interior decoration of a room of the Hamilton castle in Scotland has been reconstituted: it is noteworthy for the elegant wood panelling, and dates to the late 17th c. Above the chimney is a late 19th c. addition, a large panel featuring a coat of arms: the quarterly Hamilton and Arran with the inescutcheon of France en surtout.

The situation is very perplexing. Obviously, both dukes cannot be right at the same time: there can only be one duke of Châtellerault. The title, created by the French sovereign, ultimately depends on French laws and decisions of the French sovereign. By granting title and duchy to others after 1560, the French kings clearly indicated that they did not think that the title belonged to any descendant of James Hamilton. Nor did his heirs think that it did, since none seemed to claim the title, but rather worried about the 12,000 livres rent. That rent was taken care of, and although the 1720 bankruptcy must have been a blow, it was a blow endured by all creditors of the French state alike. No one among the Hamiltons seems to have worried about the title itself until the late 18th c.

On that basis, of course, Napoleon III was free to create the title again and bestow it on whomever it pleased him, but that is not what he did, since he claimed to have simply confirmed an existing title. If one follows the interpretation of the Conseil d'État, he recreated the title for the 12th duke, under unspecified terms of succession: but neither the duke of Abercorn nor the duke of Hamilton are descendants of the 12th duke of Hamilton. Even if one takes the view that Napoleon III somehow recreated the title created by the Letters Patent of 1548, following the terms of the remainder in those very Letters, the heir to the title is the earl of Derby, heir to the general line, and neither Hamilton nor Abercorn.

Be that as it may, it is the case that the present duke of Abercorn has no plausible claim to the title, whether or not one takes into account the 1864 decree.

Furthermore, the escutcheon which both Hamilton and Abercorn claim comes from nowhere. The only individual to have unquestionably held the title in question, that is, the grantee, apparently never used such an escutcheon, even as he used the title and coronet over his complete achievement. Furthermore, it would seem highly unusual for anyone to use a quarter or escutcheon with the arms of the king of France, unless by special grant or permission. Such a grant exists for the Stuarts of Darnley, and one can surmise that there was one for Archibald Douglas, but in both cases the grant was a quarter, not an escutcheon, and was completely independent of the title, whether a peerage or not. Thus, it cannot be said that the escutcheon of France with a ducal coronet (which no one has ever born in France) is somehow "the mark of a peerage" or the escutcheon of Châtellerault (in any event, the city of Châtellerault has its arms, namely Argent a lion gules within a bordure sable entoyré or). And, of course, under the interpretation of the 1864 decree as a new creation, one is hard put to understand why an escutcheon of the kings of France would be used to recall a title conferred by the Emperor of the French (whose arms were different).

Of course, even if one decided that the escutcheon in question, in Scots heraldry, represented the duchy of Châtellerault, it would remain that only one duke could bear the escutcheon, since only one duke can hold the title. Therefore the other, whoever that might be, would be assuming illegal arms.

The remaining question is: how are the arms of the dukes of Hamilton and Abercorn registered with Lord Lyon? The answer is given in Innes of Learney's Scots Heraldry, p.33. The achievement of the duke of Hamilton is shown, Quarterly 1 and 4, quarterly Hamilton and Arran, 2 and 3 Douglas, without inescutcheon, and the source is given as "1903, Lyon Register." Sir James Balfour Paul confirms that the arms registered for Hamilton are without inescutcheon. Hamilton's inescutcheon, then, is plainly in violation of the law of arms of Scotland.

As for Abercorn, according to James Paul, "no arms were never registered for the earls of Abercorn, but the following [Hamilton-Arran with inescutcheon of France] were recorded in Ulster's office, Ireland, in the 'Register of Knights', 20 July 1866, on the occasion of the duke being sworn as Lord-Lieutenant." I doubt that this constitutes a legal registration of those arms.

Innes of Learney discusses the use of inescutcheons: "In Scotland, the inescutcheon is often reserved for a Royal augmentation, or some highly important feudal fief or heritable office, or in other cases for the paternal arms when the shield itself is occupied with quarterings of fiefs and heiresses. […] The Scottish practice is therefore very much that of the Continent, where in the case of family arms its use often indicates the chief of the family. When, however, the inescutcheon bears the arms of a fief, the use of this marshalling indicates cadency (footnote: The duke of Abercorn, heir-male but cadet in the Hamilton family, bears an inescutcheon of “his” dukedom of Châtelherault. In Scotland his predecessors bore a label.), unless such inescutcheon is coroneted." (p.139) Another passage on marks of cadency states: "The label is the charge appropriate to be borne by the heir-male who is not the heir-of-line of his house when the principal (i.e. undifferenced) arms have gone to the heir-of-line" and a footnote says: "The Abercorn line of Hamiltons did use such a mark prior to their differencing by the inescutcheon of Chatelherault" (p. 119).

These passages are puzzling: they appear to describe the inescutcheon of Abercorn as a mark of cadency, the heir to the name and arms of Hamilton being the duke of Hamilton. That mark used to be a label, the mark of cadency for the heir-male when he is not the heir of name and arms, and this label was later replaced by the inescutcheon of a fief of the Abercorn line.

There are many problems with this theory: the inescutcheon used by the Abercorns is coroneted, which rules out this interpretation from the start, according to Innes of Learney's own remark; the inescutcheon in question is not that of the claimed fief; the claimed fief does not belong to the Abercorn line (note how Innes of Learney raises doubts on this point with the quotes around “his”); the Abercorn were using the label before they were heirs-male to the line (Claude, Lord Paisley and his son the 1st earl used a label, Stevenson and Wood); the Abercorns dropped the label sometime in the 17th c., used the arms without label and without inescutcheon in the 18th c., and do not appear to have used the inescutcheon until the mid-19th c., and therefore for close to 200 years did not use any mark of cadency whatsoever (cf. Debrett's Peerage, 1814, where Abercorn bears Hamilton and Arran).

Such an interpretation, therefore, although apparently that of Lord Lyon, is extremely dubious. It is clear that the duke of Hamilton is violating the law of arms of Scotland, and probable that the duke of Abercorn is doing the same, possibly with the ambiguous endorsement of the Lord Lyon.

John Kennedy of Dunure, who lived around 1358, had Gilbert who lived until around 1400. Gilbert in turn several sons among whom Hugh Kennedy of Ardstynchar. Sir Hugh Kennedy went to France during the Hundred Years War on the side of the French, and his valor at the battles of Baugé (1421) and Verneuil (1424) was distinguished by the king of France Charles VII, who granted him the right to quarter his arms with those of France (Burke's History of the Landed Gentry, Paul's Scots Peerage, 2:450). He died unmarried, and his estates and arms went to his younger brother Thomas Kennedy of Bargany. From Thomas are descended the Kennedy of Bargany, Bennan, Kirkhill and Bandrochat. In 1549, Sir David Lindsay blazoned their arms as quarterly France and Kennedy (which is Argent a chevron gules between three crosses crosslets fitchee sable, all within a double trssure flory-counterflory of the second). The line was represented in the mid-19th century by Hew-Fergussone Kennedy of Bonnane, born in 1801, thought to be the head of the line. His descendant Charles Fergusson Kennedy, 10th of Bonnane, sold the estate in the 1920s and moved to Australia, where his address was Blackman's River, Dunally, Tasmania (Burke's Landed Gentry). This line was still using the coat of France in its arms.

Allegedly descended from the house of Montgomery in Normandy through a companion of the Conqueror, the Scottish house of Montgomerie is traced to Robert of Montgomerie, who obtained Eaglesham from Walter the First Stewart of Scotland, and died in 1177. Alexander Montgomerie of Eaglesham, son-in-law of the first earl of Douglas, died in 1380 and was succeeded by Sir John Montgomerie, who married the heiress of Lord Eglinton, died in 1398. All descendants of his eldest son John Montgomerie of Ardrossan († 1428) share a quarter of France in their arms. This includes the main line from the second John's eldest son Alexander, created baron of Montgomerie ca. 1445 († 1470), from whom are descended the earls of Eglinton and the (extinct) earls of Mount-Alexander, as well as the Montgomeries of Skermorlie. A grandson of Alexander, Robert, went to France in the early 16th c., and became seigneur des Lorges. His arms were quarterly, gules three escallop-shells or, and Azure three fleurs-de-lis or. His son Jacques bought the original land of Montgomery in Normandy in 1543, and eventually became captain of the King's elite Scottish Guards; Jacques' son Gabriel accidently killed the king of France Henri II in a tournament in 1559 and was executed in 1574 on officially unrelated charges of treason (he had converted to Protestantism and taken up arms against the king); his descent died in 1721.

The present earls of Eglinton bear a quarterly of Montgomery and Seton, with Montgomery itself being quarterly Montgomery (azure three fleurs-de-lis or) and Eglinton (gules three annulets or stoned azure) within a bordure or charged with a Royal Tressure of Scotland (double tressure flory-counterflory gules). The Montgomeries of Eglinton had born this quartered coat since Alexander, first baron of Montgomerie, on a seal dated 1457. Only two earlier seals are known. The oldest, from around 1170, belonged to John of Montgomery of Eglesham, and it shows a fleur-de-lis flory, but not within a shield. Sir John Montgomerie, his descendant, who married the heiress of Lord Eglinton, bore on his seal of 1392 an annulet stoned between three fleurs-de-lis, no doubt a form of marshalling (both seals are in Macdonald, the second one is also in the Catalogue of Seals in the British Museum). It appears, then, that the arms of Montgomery probably precede the adoption of the three fleurs-de-lis by France ca. 1376 (which hitherto bore a semy).

Montgomery

County, in Maryland, bears Quarterly per fess embattled azure a

fleur-de-lys or and gules an annulet or stoned azure. The mantling

is azure and or, the crest, out of a mural coronet an arm in armor argent

holding a broken lance or, between two banners the dexter or and the sinister

sable. The motto is "Gardez bien". The county is named for Richard

Montgomery (1736-75), a major-general killed in the American assault on

Quebec City. He was born in Dublin, and belonged to the Montgomery of Beaulieu

(Burke's Landed Gentry, 1866).

Montgomery

County, in Maryland, bears Quarterly per fess embattled azure a

fleur-de-lys or and gules an annulet or stoned azure. The mantling

is azure and or, the crest, out of a mural coronet an arm in armor argent

holding a broken lance or, between two banners the dexter or and the sinister

sable. The motto is "Gardez bien". The county is named for Richard

Montgomery (1736-75), a major-general killed in the American assault on

Quebec City. He was born in Dublin, and belonged to the Montgomery of Beaulieu

(Burke's Landed Gentry, 1866).