Nobility and Titles in France

See also several articles on this topic on Caltrap's

Corner.

Contents

Current Status in French law

Online Resources

Bibliography

History of Nobility

The Nature of Nobility

The French concept of nobility was very different from the English one.

Whereas, in England, only a peerage bestows nobility on the holder, in

France, nobility was a quality, a legal characteristic of the individual,

which was held or acquired in specified ways, and which conferred specified

rights and privileges. The manners of acquiring nobility being specific,

French nobility isn't the same as the English

gentry either, which has no legal definition or status.

Nobility was usually a hereditary characteristic, but some forms of

nobility could not be transmitted. When it was hereditary, nobility usually

came from the father, but sometimes a higher percentage of noble blood

might be required (counted in number of "quartiers") or that the family

be noble for a certain number of generations. A nobleman marrying a commoner

did not lose his nobility, but a noblewoman who married a commoner lost

it, as long as she was married to the commoner.

Nobility was an important legal concept, in particular because of the

privileges attached to it. Taxes were originally levied to help the sovereign

in times of war; and since nobles were expected to provide help in kind,

by fighting for their sovereign, they were usually exempted from taxes.

This privilege lost its rationale after the end of feudalism and nobility

had nothing to do with military activity, but it survived for the older

forms of taxation until 1789 (more recent taxes, levied in the 17th and

18th centuries, allowed for weaker or no exemption for nobles).

A number of offices and positions in civil and military administrations

were reserved for nobles, notably all commissions as officers in the army.

This privilege created a significant obstacle to social mobility and to

the emergence of new talents in the French state. It remained very real

until 1789.

Acquisition of Nobility

But one could also acquire nobility, and that was a numerically significant

mode since the 16th c.

There were three main ways one could be noble:

-

by birth: usually, but not always, from the father, and the mother

could be a commoner. Some regions in Eastern France allowed for transmission

of nobility by the mother, notable Champagne at least until the 16th century,

and Bar until 1789 (subject to the prince's approval), but otherwise an

edict of 1370 restricted transmission to the father. Bastards of nobles

became noble when legitimated by letters of the sovereign, until 1600 when

a separate act of ennoblement was required (royal bastards were always

noble, even without legitimation).

-

by office: depending on the office, the holder of the office became

noble eirher immediately or after a number of years, nobility was personal

or hereditary, hereditary for 2, 3 or more generations, etc. There were

about 4000 offices conferring nobility of some kind in the 18th century.

Nobility thus attained was called "noblesse de robe" (for judicial offices;

"noblesse de cloche" for municipal offices). Offices were usually bought,

and oftentimes they were sold once ennoblement had occurred. The types

of offices were varied:

-

municipal offices (in sixteen French towns: Angers, Angoulême, Arras,

Bourges, Cognac, Issoudun, La Rochelle, Le Mans, Lyon, Nantes, Niort, Paris,

Poitiers, Saint-Jean d'Angély, Toulouse, Tours). The offices were

usually those of aldermen or members of the city council, but after 1667

the ennobling privilege was restricted to the office of mayor, except for

Lyon (comtes de Lyon) and Toulouse (capitouls). The registered burghers

of Perpignan were considered noble, an Aragonese privilege confirmed after

French annexion.

-

judicial offices: members of the courts or Parlements were ennobled after

20 years or death in office for two consecutive generations (some courts,

such as Paris, ennobled "in the first degree", that is, at the first generation);

a variety of other judicial offices carried similar privilege. These offices

were bought and sold freely.

-

fiscal offices: members of the tax courts and state auditors, senior tax

collectors and the like; also bought and sold.

-

administrative offices: various positions in the king's household, and

the several hundred offices of secrétaires du Roi, which ennobled

in the first degree, and were bought and sold.

-

military commissions: in the Middle ages, the owner of a noble fief could

be ennobled if he wasn't so, but after 1275 a condition that three consecutive

generations hold the fief ("tierce foi") was added, and the privilege was

abolished in 1579. The Edict of

November 1750, when some military commissions were opened

to non-nobles, it was decided that officers reaching the rank of general

would automatically receive hereditary nobility. Officers of lesser rank

who received the Order of Saint-Louis and fulfilled certain requirements

were exempt from the taille (a tax on non-nobles); the third

generation meeting the requirements received hereditary nobility.

-

by "letters": that is, by royal grant. The king could always

ennoble anyone he wished. The earliest examples date from the last third

of the 13th century. In times of financial distress, the king sold such

letters of nobility, sending them blank to his provincial administrators.

Note that one could lose nobility, by failing at one's feudal duties ("déchéance")

or practising forbidden occupations ("dérogeance"): commerce, manual

crafts were cause to lose nobility. Medicine, glass-blowing, exploitation

of mines, maritime commerce, and wholesale commerce were exempted. Tilling

one's land was acceptable, but farming someone else's (except the King's)

was not.

A nobleman son and grandson of nobles was called a noble de race

or gentilhomme (although the term of gentilhomme is often used for

any noble by birth). If all 4 of his grandparents were noble he was a gentilhomme

des 4 lignes (nobility of all lines, and not just the paternal line,

was usually of little importance in France, though a prestigious lineage

in female line could be a source of pride; the emphasis on nobility in

all lines may be due to the particular requirements for admission into

the Order of Malta from the 16th century). If his pedigree went further

and no commoners could be found in the male lign, he was deemed a gentilhomme

de nom et d'armes. These definitions vary from author to author, and

are not very important. In general, the status depends primarily on the

length of the pedigree, and everyone agrees that a gentilhomme is a born

noble: not even the king can make a man into a gentilhomme. Adoption did

not transmit nobility.

Numbers

In 1789, there were 17,000 to 25,000 noble families, and estimates of numbers

of individuals range from 80,000 (many contemporary estimates) to 350,000.

Chaussinand-Nogaret finds 110,000 to 120,000 nobles, for 1/4 of which nobility

had been acquired during the 18th c.(25,000 families, of which 6,500 ennobled,

about 1,000 by letters and the rest by office). I would tend to believe

him, rather than the 300,000 figure. The population of France was 28 millions,

so that's 0.4% of the population. Nowadays, there are about 3500 families

of noble origin, of which about 3000 from before 1789. Not that the Revolution

itself is to blame for the losses: only 1200 nobles were tried and executed

during the Terror, and maybe 30,000 to 40,000 emigrated, almost all of

whom returned eventually.

Number of noble families in France:

| 1789 |

25,000 |

Chaussinand-Nogaret (17,000 d'Expilly) |

| 1900 |

5,033 |

Séréville and Saint-Simon |

| 1927 |

5,151 |

Woëlmont de Brumagne |

| 1947 |

4,528 |

Jougla de Morenas |

| 1975 |

4,057 |

Séréville and Saint-Simon |

| 1977 |

3,508 |

Valette |

The discrepancies are due in part to the difficulty in determining nobility

in a number of cases.

The decomposition of today's noble families in terms of origin is as

follows (Séréville and Saint-Simon):

1) pre-1789

nobility of knightly origin (14th c.) 365

nobility of ancient origin (15th c.) 434

nobility of origin (16th c.) 801

ennobled by Letters Patent 640

ennobled by office 1010

annexed territories, foreign nobility 244

Total nobility of pre-1789 origin 3494

2) 19th century

First Empire (1808-15) 239

Restoration (1815-30) 267

July Monarchy (1830-48) 21

Second Empire (1852-70) 36

Total 19th century 563

The first three categories are collectively called "noblesse d'extraction",

families for which there is no trace of ennoblement (equivalent to the

German Uradel). The three categories are defined depending on how

far back a proven line of descent can be traced. The first category also

requires that the first traceable ancestor be a knight. Further refinements

can of course be made: feudal nobility is made of families whose existence

is known in feudal times (12th c. or earlier) and whose line of descent

goes back to 1250 at least (there are about 50). About 160 existing families

can prove that one of theirs was a Crusader (11th-13th c.).

Titles of Nobility

The status of nobility was thus a personal quality, inherited or acquired.

Titles of nobility were a rank attached to certain pieces of land.

The two (nobility and titles) are therefore separate, although nobility

was a pre-condition for bearing a title of nobility. This explains,

in particular, why so many noble families were untitled (see below).

Historically, titles went through three phases.

-

They were originally (6th-12th c.) offices or functions which became (a)

hereditary and (b) attached to the ownership of specific pieces of land;

-

later (13th.-18th c.), they were a special status attached by the king

to specific pieces of land, inheritable along with the land subject to

certain rules;

-

finally (19th c.-20th c.), titles became simply hereditary appendages of

the family name.

We now look at these three phases in turn.

1. Titles as offices (6th-12th c.)

The origin of modern titles like duke, marquis, count lie in public offices

held under Merovingian kings (6th-8th c.).

-

A duke (Latin dux, literally "leader") was the governor of a province,

usually a military leader.

-

A count (Latin comes, literally "companion") was an appointee of

the king governing a city and its immediate surroundings, or else a high-ranking

official in the king's immediate entourage (the latter called "palace counts"

or "counts Palatine").

-

A marquis was a count who was also the governor of a "march", a region

at the boundaries of the kingdom that needed particular protection against

foreign incursions (margrave in German).

-

A viscount was the lieutenant of a count, either when the count was too

busy to stay at home, or when the county was held by the king himself

-

A baron (a later title) was originally a direct vassal of the king, or

of a major feudal lord like a duke or a count

-

A castellan (châtelain) was the commander in charge of a castle.

A few castellanies survived with the title of "sire".

These offices became hereditary and attached to land over the course of

time. The connection to land came both from the fact that these offices

corresponded to regional units of administration, but also because kings,

rather than pay their officers' salary in cash, paid them by giving them

pieces of land, whose income was to represent the officer's wages.

Although appointments were initially for life at the longest, both the

land endowment (the "benefice") and the office itself became hereditary.

In the later part of this period (9th-12th c.), the feudal system

emerged, which brought a coherent system by establishing contractual relationships

between all members of society, from the king down to the peasant.

The holders of offices were naturally integrated in these chains of relationships,

being vassals of the king or another great lord (who owed them protection

and to whom they owed loyalty and support). They, in turn, were able

to create their own vassals, by "infeoffing" land in their jurisdiction

to others who became their vassals. Hence the origin of baronies

and lordships.

The French kings were successful in reuniting the country and asserting

their central authority to the detriment of the great dukes and counts.

As a result, the governmental powers which had been lost to them over time

were brought back again in the hands of the king. It became accepted

that such powers as titled nobles did hold came ultimately from the king

himself. Over time, by a combination of marriages, purchases and

confiscations, the king of France managed to unite with the crown virtually

all the ancient titles of duke, marquis and count. This process was

pretty much complete by the 16th c., so that, with a handful of exceptions,

titles of duke, marquis, count, or viscounts in existence after 1600 are

created rather than feudal in origin.

A few feudal titles of viscount, baron and vidame made it down past

1500. Here are a few examples, with the names of the families that

owned them:

-

counties:

-

Nevers (with Rethel and the baronny of Donzy): passed to Courtenay

1192, Bourgogne 1266, Flanders 1280, raised to a peerage 1347, 1459, 1464,

1515; Bourgogne 1385, Clèves 1491, raised to a duchy-peerage

1539; passed to Gonzague 1601; sold to Mazarin 1659; raised to a duchy-peerage

1660

-

Tonnerre (Bourgogne): to Bourgogne, to Châlon 1346, to Husson

1453, to Clermont 1540, raised to a duchy-peerage 1572, sold 1684 to Louvois

-

Saint-Pol (Artois): to Châtillon 1219, to Luxembourg 1371,

to Bourbon 1495, to Longueville 1601, sold to Elisabeth de Lorraine-Lillebonne,

princess of Epinoy; passed on the death of her son in 1724 to his sister,

princesse de Soubise

-

Vendôme: to Bourbon 1412, not united to the crown when Henri

IV acceded but given by him to his mistress Gabrielle d'Estrées

and her issue, extinct 1712, at which time it went to the crown

-

Armagnac: to Alençon 1497, to Albret 1549, united to the

crown 1589 on the accession of Henri IV

-

Blois and Châteaudun/Dunois: sold to Louis d'Orléans

1397, united to the crown 1498 on the accession of Louis XII

-

Foix, Comminges: passed to Albret, then united to crown 1589

-

viscountcies were common in particular areas like Limousin, Poitou

and Gascogne.

-

Limoges (Limousin): to the Comborn family in the 12th c., the dukes

of Brittany in 1301, to Châtillon-Blois family in 1384, to Albret

in 1481, united to the crown in 1589

-

Turenne (Limousin): to Comborn in 10th c., to Comminges in 1335,

sold in 1350 to Beaufort, to La Tour in 1490, sold to the crown in 1738

-

Comborn (Limousin): in the family of that name, to Pompadour in

the 16th c., family extinct early 18th c.

-

Ventadour (Limousin): raised to a county 1350, to a duchy 1578,

to a duchy-peerage 1589; passed to Rohan-Rohan in 1727.

-

Lavedan (Gascogne): late 15th c. to Charles, bastard of Bourbon;

to gontaut in 1610; to Philippe de Montault, raised to a duchy in 1650

-

Narbonne: to Lara in 1193, sold 1447 to Foix, exchanged with the

crown against Nemours in 1507

-

Thouars (Poitou): to Amboise, to La Trémoille 1446, raised

to a duchy 1563, duchy-peerage 1595

-

Rohan (Bretagne): in the Rohan family, 1648 to the Rohan-Chabot

family; raised to a duchy-peerage 1603, and again in 1648

-

numerous viscountcies in Gascogne:

-

Couserans (to Comminges, Foix, Mauléon, Modave, Polignac)

-

Fézansaguet (to Armagnac 1140)

-

Gabardan

-

Gimois

-

Labourd

-

Magnoac

-

Maremnes

-

Marsan

-

Nébouzan

-

Quatre-Vallées

-

Soule

-

Tursan

-

vidames: see special page

-

"sireries", which were lordships of high standing or castellanies:

-

Pons (Saintonge): to Albret de Miossans 16th c., to Lorraine afterwards

-

Mortagne (Saintonge): to Aulnay, Clermont, Montberon, Coetivy, Matignon,

Loménie

-

Coucy: divided in 1397, part to Orléans (united to the crown

1498), part to Luxembourg, then Bourbon (united to the crown 1589)

-

Beaujeu (with Dombes): ceded 1400 to the duc de Bourbon

-

Craon: to La Trémoille

-

Sully: to La Trémoille, sold 1602 to Maximilien de Béthune,

raised to a duchy-peerage 1606

2. Created titles (13th-18th c.)

From the 14th c. onwards, French kings began to create titles, initially

dukes and counts (at first mostly for members of the royal family), and

starting in 1505, marquis as well. Whereas the old titles had arisen

by custom centuries before and originally corresponded to an administrative

function, the new titles were a status attached to certain fiefs, which

(except in the case of apanages) conferred only

a small fraction of the powers and privileges that went with the old offices.

The new titles were created by a written act of the king, letters

patent, which specified the rights and duties of the new titled person,

and the mode of transmission of the title to his heirs. The

letters patent of creation might place particular restrictions on inheritance

or create specific remainders (see the examples of peerages).

The letters patent had to be registered by the court (parlement)

of the region where the fief was located, as well as by the Chambre

des Comptes, a fiscal auditing body, before they could be valid.

It is important to understand that a created title is nothing but a

fief (that is, a particular type of real estate in the feudal system),

to which the king has given a special status. The rules of transmission

remain that of a fief, except to the degree that the special status modifies

them. (In principle, fiefs that had been raised to be fiefs of dignity

were to return to the crown upon extinction of the heirs of the grantee;

but this was not enforced in practice). Fiefs to which the king had

added a rank were called royal fiefs (because the king became the

overlord of such fief, no matter who the previous overlord was) or fiefs

of dignity, because the attachment of a dignité was their

distinguishing characteristic. (The word dignité in

general designated other ranks or positions that had some official definition,

like clerical or judicial ranks).

An important difference with simple fiefs is that "fiefs of dignity"

were indivisible, because originally only one person could hold

the office (ordinary fiefs, on the other hand, could be shared).

French titles are thus born by one person at a time, because only

one person can own the property. The equivalent of Northern European and

German titles born by all members of a family or unattached to a land does

not exist (with rare exceptions in provinces annexed in the East). However,

a family might possess several titles, and the head of the family might

distribute them among his heirs, as he would share his inheritance between

his children. Indeed, titles were a form of property, and could be bought

and sold freely before the abolition of the feudal regime in 1789.

All titles, whether feudal or created, were attached to a specific

piece of real estate, governed by the rules of the feudal system.

The legal maxim was "pas de seigneur sans terre, pas de terre sans seigneur":

no lord without land, no land without lord. And a title-holder was

nothing but a particular type of lord. The owner of the land to which

the title was attached, if noble, had the exclusive right to bear the title.

If he lost or sold the land, he lost the title. The land, and with it the

title, followed special rules of inheritance of noble fiefs (usually by

male primogeniture with succession by females in default of males), but

the remainders could be modified, sometimes in very complicated ways, by

will of the owner. The inheritor or purchaser of a land could use the title

after payment of a tax and the (usually) automatic authorisation of the

sovereign, if he was noble. There was also a custom that, for commoners,

the 4th generation of possessors of a titled land could use the title.

But the ordonnance of Blois of 1578 made it impossible for a commoner who

purchased a titled fief (fief de dignité) to acquire the

title; however, it implicitly allowed that a noble purchaser could acquire

the title, although some jurists thought that the purchaser required the

assent of the king. A commoner owning a county could call himself

"lord of the county of X", and collect feudal dues and domanial rights,

but he was not "count of X".

As always, there are exceptions. Louis XIV was the

first to create "titres de pur honneur", that is, titles without fiefs:

marquis d'Auray in 1700, marquis Le Camus, marquis de Pillot les

Chantrons in 1780 (see other examples cited by Alain Texier, Qu'est-ce

que la noblesse?, p. 63). . There are also the "ducs à

brevet", which were life-time grants of the precedence of dukes to particular

individuals, oftentimes eldest sons of dukes. An edict of 1770

made it possible to obtain a brevet of duc, marquis, comte or baron upon

payment of a tax.

It might still be worthwhile for a commoner to buy a titled fief,

as an investment. The return came not only from the agricultural activities

on the land, but also from collecting various rents and dues, as well as

fees and fines. In 18th century newspapers, it was common to see fiefs

advertised for sale, as in the example below.

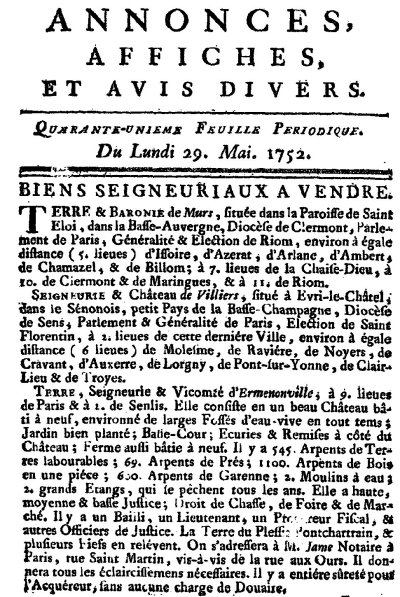

Lordships for sale from the bi-weekly Affiches, Annonces et Avis Divers,

29 May 1752. Notice that the third item for sale, Ermenonville, is a viscountcy, and

is the place where the philosopher and writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau was buried in 1778.

The advert describes the buildings (nice castle, recently built, with moat; stables,

farm building, etc); lists the areas of land (field, pasture, woods, etc; 1 arpent

= 1.25 acre). It carries with it the right to dispense justice, and several

judicial officers are listed (they would be employees of the lord). It mentions

by name one fief whose owner is a vassal of Ermenonville.

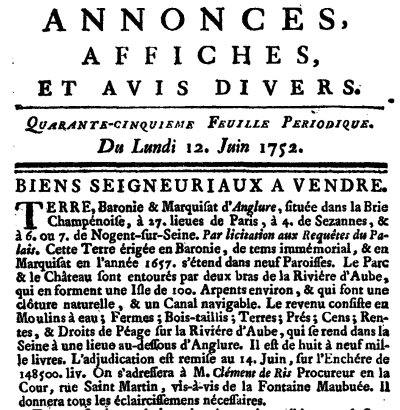

Advert from 12 June 1752. This is a is a marquisate, apparently auctioned

in order to divide an inheritance. It says the title of barony dates from

"time out of memory", and the title of marquis was created 1657. The lordship spreads

over 9 parishes. Revenue is given as 8 to 9000 F (about £300 at contemporary

exchange rates), the initial bid is 148500. Revenue comes not only from the lands

comprising the domain, but also the fees and rents collected (cens & rentes), and a

right to levy a toll on the

nearby river. Of course, the purchaser would have to receive the king's permission

in order to bear the title of marquis, but, if noble, he could call himself

baron d'Anglure. otherwise, he would just be "seigneur d'Anglure".

Created titles could not be transferred with the sale of the land, unless

allowed by the sovereign, so created titles usually become extinct with

the last descendant of the grantee. The letters patent of creation, to

be valid, had to be registered by the appropriate courts, and the appropriate

taxes paid. Oftentimes a land on which a pre-existing title existed (say,

count) was elevated to a higher title, such as duke; upon extinction of

the ducal title, the land reverted to being a county.

There existed a notional hierarchy of titles. An edict of 1575,

rarely enforced, established a minimum size and income for the land to

which the created title was attached, thus establishing a hierarchy which

was purely notional:

-

duc (duke)

-

marquis (marquis)

-

comte (earl)

-

vicomte (viscount)

-

baron (baron)

Another rare title, usually considered below baron, was vidame.

There were no creations of the title of vidame.

It should be emphasized that this hierarchy is notional, and implied

little in terms of privileges, precedence, etc. The only real differences

were between

-

dukes-peers (peerages had special privileges

attached to them),

-

other dukes,

-

all other titled noblemen,

-

untitled noblemen..

In everyone's eyes, the most important factors in determining a family's

prestige were:

-

how long had a given family been noble (l'ancienneté),

-

into what other families did it marry (les alliances),

-

what positions its members achieved and what offices they held (les

dignités),

-

what actions they performed (les illustrations).

Among nobles, one also distinguished between

chevalier and écuyer..

These were not titles, but ranks within the nobility (with

some exceptions; see further details).

Any nobleman, no matter how recent, was

an écuyer, and only noblemen could be styled as such.

Chevaliers (knights) were a subset of the nobility, which included all

titled nobility, members of the orders of knighthood of the king, but also

members of families of ancient nobility, even untitled. The legal

definition of a chevalier was very unclear, whether it was a matter of

ancestry or a matter of eminence. In legal documents, those whose nobility

traced to 1410 or earlier were called haut et puissant seigneur,

while those whose families were connected by marriage to the royal house

were très haut et très puissant seigneur. Foreign

princes and princes of the blood were entitled to similar variations on

the rank of prince.

It should be noted that "chevalier" was also used to refer to a member

of an order such as the Knights of Saint John (a.k.a. Order of Malta) as

well as members of royal orders: the use of the term makes it similar to

a title (the chevalier d'Ancenis) but it was not; it simply indicated membership

in such an order, a very common occupation for younger sons of the nobility.

Lord (seigneur) was not a title. The owner

of a lordship, even a commoner, was its lord. The term "lord" only

meant "the possessor of a certain kind of property" in the feudal system,

a mixture of actual real estate and rights over people (rents and fees

could be collected from them, certain obligations could be imposed on them,

etc). Someone who was only a seigneur was not titled.

All lordships disappeared when feudalism was abolished in 1789.

3. Titles as part of the name (19th c.-20th c.)

The Revolution abolished the feudal system on 4 Aug 1789. This completely

removed the legal foundation of titles. Titles of nobility were explicitly

abolished 19-23 June 1790.

When Napoleon brought back titles, starting with the great officers

of state in 1804 and the grand-fiefs of the Empire in 1806, and then the

whole hierarchy of dukes, counts and barons in 1808, he did not restore

feudalism. He did try to give titles a landed basis, by laying down

as rule that a title, to become hereditary, had to be formally attached

to a land endowment called a "majorat", whose contents had to be provided

by the title-holder, and whose inheritance followed special rules (to avoid

division at each generation). The Restoration regime extended the

system to the peerage it created in 1817, and to all other titles in 1824.

The requirement of a the majorat, however, was abolished in 1835, so titles

were completely divorced from any landed connection. Furthermore,

from 1814 to 1824 a large number of hereditary titles were created that

were not attached to any land. This was, in a way, completing an evolution

that had started with the multiplication of "titres de pur honneur" in

the 18th c.

French titles continued to exist, and many were created until 1870,

when France permanently became a Republic. The Republic did not abolish

titles, however, and, based on existing laws and earlier jurisprudence,

the courts have built up a legal system to deal with titles and their transmission.

This is discussed in greater detail below.

Titled and Untitled Nobility

One has to be noble to be titled, but one could be noble without being

titled.

The untitled nobility was always more numerous than the titled nobility.

The difference between titled and untitled may not be so much due to the

antiquity of the lineage as to the good fortune of some families on whom

the sovereign bestowed titles. Since the mid-19th century, however, usage

has become very lax, and little regard is paid to the authenticity of titles

which people use; though no one usurps ducal titles which are too rare,

there are many more people called marquis and comte than there should be.

Of the 4,000 or so noble families existing today, only about 1,000 have

authentic titles (1/3 of pre-1789 origin and 2/3 19th century), the rest

consisting of untitled nobility. There are 38 ducal titles still in existence,

of which 22 are pre-1789. Only one title of prince

created under Napoleon I is still in existence (see the page on peerages

for more information on ducal titles).

Usurpation of titles had become quite common in the 18th century already.

Even commoners adopted counts' and marquis' coronets in their arms. In

many cases, the usurpation was politely tolerated and, over the course

of a few generations, became accepted in legal documents, or even at the

Court, although such recognition was never equivalent to a formal grant

of title. Such titles are known as "titres de courtoisie". In the

19th and 20th centuries, such usurpation became commonplace, and many untitled

families call themselves count and marquis today.

During the Restoration period (1814-48), a House

of Peers was created on the British model. For peers, a "declension

of titles" was introduced as a form of courtesy title: whereas a British

peer is created wih an assortment of lower-ranking titles for use by his

heirs, in France the eldest son of the duke of X was called marquis of

X, his eldest son was called count of X, etc. Later, this practice was

informally extended to all titles, so that the children of a marquis call

themselves count.

In modern usage, it is common to distinguish between the actual holder

of a title: Pierre, comte de Sassafras and other members of the

family who will call themselves comte Jean de Sassafras. This usage

was unknown before the late 19th century.

The "Particule"

The "particule" (the word "de" between the given name and the family name)

is often taken to be a sign of nobility.

In fact, there are about 10,000 names in France that look noble (e.g.,

with the particle "de"), many more than are really noble.

Conversely, there are noble families

without the particle in their name: a large number of Napoleonic and 19th

c. titled names which have no "de" element; but also families of Old Regime

nobility which did not bother to add a particule to their name. There

are several examples among the old "noblesse de robe": Séguier,

ennobled in 1544, Talon ennobled in 16th c., Molé.

It is possible to change one's name in France, though it is an arduous

and costly process. Some families have changed their names and given it

a nobiliary appearance. It is also possible to re-use a name which has

become extinct (relever un nom): one needs to make sure that there

is no one still entitled to bear that name, and obtain a decree of the

Conseil d'Etat. This was the procedure followed by a M. Giscard, who legally

changed his name to Giscard d'Estaing (the family d'Estaing became

extinct with the execution of the admiral d'Estaing in 1794). such a procedure

does not make anyone noble, obviously. His grandson, president of the French

Republic (1974-81), ridiculed himself by asking for the seat of the admiral

in the Society of the Cincinnati (he was admitted on an honorary basis).

Nobility and Titles in France since 1790

Brief Legal History since 1790

Briefly put, the legal status of nobility was abolished in 1789 and never

recreated. Titles of nobility, as hereditary marks of honor,

were recreated in 1808, abolished in 1848, restored in 1852 and have remained

in existence ever since, to this day.

The Revolution broke in many ways with the Old Regime. The legal class

of nobility, as one of the fundamental remaining elements of feudalism,

was abolished along with the feudal regime on August 4, 1789, which established

legal equiality of all individuals regardless of birth. Furthermore, titles

of nobility were abolished by a decree of the National Assembly of June

19, 1790, signed by king Louis XVI.

On March 1, 1808, Napoleon, Emperor of the French, established a legal

system of titles, but the word "nobility" is

not used anywhere in legal texts, and no privileges were attached to it.

Nevertheless, in common parlance it is often called nobility ("noblesse

d'Empire"). Titles were created by Letters Patent of the Emperor, or, for

the most part, were automatic and came with certain positions. However,

the titles did not become hereditary until certain conditions were met

(in particular the constitution by the grantee of an endowment in land

to be attached to the title, the majorat), and a newly created Conseil

du Sceau des Titres was in charge of verifying compliance (see more

on Napoleonic titles).

After the fall of Napoleon's Empire, the Bourbon kings returned to France.

On June 6, 1814, Louis XVIII granted a Royal Charter (equivalent of a constitution)

whose article 71 specified:

The new nobility keeps its titles and the old nobility

regains its titles. The king creates nobles at will, but he grants them

only ranks and honors without any exemption from the burdens and duties

of society.

La noblesse ancienne reprend ses titres. La nouvelle

conserve les siens. Le roi fait des nobles a volonté, mais il ne

leur accorde que des rangs et des honneurs sans aucune exemption des charges

et des devoirs de la société.

The "charges" really mean taxes: nobility's exemption from a number

of taxes in Old Regime France had been one of the major grievances in 1789.

Louis XVIII established a House of hereditary Peers on the English model

(although peers became life-peers in 1830). The Conseil du Sceau des Titres

was replaced by a Commission du Sceau, presided by the minister of Justice

(Ordinance, July 15, 1814). It was abolished by an ordinance of Oct. 31,

1830 and all its functions transfered to the Conseil d'administration

of the Ministry of Justice.

When the monarchy was overthrown in 1848, nobility was again abolished

(Feb. 29, 1848), but the decree was rescinded on Jan. 24, 1852 after Napoleon

III restored the Empire. The Conseil du Sceau des Titres

was recreated by decree of Jan. 8, 1859. The Second Empire fell on Sep.

4, 1870, and a decree of Jan. 10, 1872 declared that the Conseil had ceased

to function since that date and transferred its activities, to the degree

that they did not conflict with existing legislation, to the Conseil d'administration

of the Ministry of Justice. The President of the Republic made a decision

on May 10, 1875 that he would cease to confer or confirm titles, and this

decision has never been reversed by any of his successors. The Conseil

expressed in 1876 the opinion that the President should not confirm foreign

titles either, but this has nevertheless happened twice (for a Papal title

of count in 1893 and for a Spanish ducal title in 1961).

Titles of nobility since 1808

Titles have been granted from 1808 to 1848 and from 1852 to 1870, when

the President of the Republic effectively relinquished the exercise of

any prerogative in the matter. The process was well-defined: letters patent

had to be issued and certain legal conditions had to be met for the title

to be valid and hereditary.

Napoleon's titles are discussed in greater detail elsewhere.

The titles granted by Louis XVIII (1814-24) and Charles X (1824-30) were

of two kinds:

-

peerages: part of the 1814 constitution was a House of Peers modelled on

the British House of Lords; titles ranging from baron-peer to duke-peer

were created (see a fuller discussion)

-

non-peerages: titles from baron to duc were created and,

although hereditary, they did not give any access to the House of Peers.

They were, however, subject to the requirement of the creation of a majorat.

The title of chavelier was also created under special

circumstances.

The title of duke was a hereditary peerage, but with some exceptions: letters

of 14 Oct 1826 created a life title of duchess (without peerage) for Joséphine

de Montault de Navailles, widow of Charles-Michel de Gontaut Biron, governess

of the children of France (d. 1862).

The Restoration also granted letters of ennoblement.

Current Status and Recent History

-

There is no such thing as nobility in France today. French courts

have held that the concept of nobility is incompatible with the equality

of all citizens before the law proclaimed in the Declaration

of the Rights of Man of 1789, which is legally part of the Constitution

of 1958.

-

However, there are titles, which are considered part of the legal

name, and entitled to the same protections in French civil and criminal

courts, even though they give no privilege or precedence (the way they

do in Great Britain). Regulation of titles is carried out by a bureau of

the Ministry of Justice.

This seeming paradox is disconcerting. It stems from several facts:

-

the abolition of feudalism and privileges in 1789, which did away with

the legal status of nobility,

-

the restoration of titles in 1808 by Napoleon, and their confirmation by

the successive monarchical regimes until 1870

-

the fact that the successive republican regimes have never passed any laws

on the subject of titles.

The Revolution did away with nobility and titles, titles were restored

(not nobility), and the Republic has not done anything about titles.

How to reconcile these facts? The kings and successive governments

did not resolve the problem with very explicit laws. The courts were

left to resolve it on their own, through a process of jurisprudence.

Thus, French nobiliary law is mostly based on court cases.

Current Status of Titles of Nobility in France

At present, titles have not been abolished. The final establishment of

a Republic in 1875 left them in a kind of limbo, and it took a succession

of court cases to define the jurisprudence, which is now well established.

The President has ceased to confer or confirm titles, but the French state

still verifies them, civil courts can protect them, criminal courts

can prosecute their abuse.

Titles as Part of the Name

Titles, to the degree that they exist in French law (that is, represent

enforceable rights and obligations), exist as part of the family name or

patronym, and get the same protection in civil courts as the latter.

"Les titres nobiliaires, dépouillés aujourd'hui

de tout privilège féodal et même de tout privilège

de rang, n'ont plus qu'un caractère personnel et honorofique et

ne peuvent même plus être considérés, du point

de vue juridique, que comme un complément du nom patronymique permettant

de mieux distinguer l'identité des personnes, tout en perpétuant

de grands souvenirs; si, en vertu de cette sorte de lien de subordination

entre le titre nobiliaire et le nom patronymique, il est dû la même

protection au titre qu'au nom, on ne lui doit pas une protection spéciale

et privilégiée." Paris, 2 Jan 1896. Dalloz 1896 2.328

Titles are not a full part of the family name, however, for a variety

of reasons: they are not inherited by all children equally, but rather

follow the rules of inheritance determined by the original grant or act

of creation. Also, no one can be forced to use his title. Titles are, however,

accessories

of the family name, complements which help to distinguish among members

of a family. As such, they are entitled to the same legal protection from

usurpation as the family name.

"Si le titre de comte comme tout autre titre quelconque

ne fait pas partie intégrante du nom patronymique puisque les titulaires

ne sont pas tenus de l'ajouter à leur nom en vertu de la maxime

"n'est titré qui ne veut", du moins ce titre se rattache au nom

comme un complément permettant de mieux distinguer l'identité

des personnes. Par suite, ce titre doit bénéficier

de la même protection légale que le nom lui-même, ceux

qui en sont investis ayant intérêt tout à la fois à

en défendre la propriété et à prévenir

des confusions préjudiciables"; Tribunal de Paris, 18 juillet 1893;

Dalloz 1893, 2.7

"...à la vérité, le titre ne se

confond pas avec le nom et ne forme pas avec lui un tout indivisible; des

règles particulières président à la transmission

du nom qui passe avec le sang à tous les descendants indéfiniment,

sans distinction du sexe, tandis que le titre ne se transmet qu'aux descendants

mâles, par ordre de primogéniture, suivant la loi de son origine"

Paris, 2 Jan 1896. Dalloz 1896 2.328

"Doivent être respectées pour un titre les

conditions de transmissibilité qui lui sont imposées par

l'acte de création." Trib. Civil Seine, 25 Jan 1928.

"Si les titres nobiliaires n'entraînent plus de

privilèges d'aucune sorte, ils n'en doivent pas moins être

maintenus dans le caractère qui leur a été donné

à l'origine, en tant qu'il est compatible avec l'ordre social, et

dans les conditions de transmissibilité qui leur ont été

imposées par l'acte de création." Cour de Cassation

25 Oct 1898. Dalloz 1899 1.168

Although some pre-1789 titles could be inherited in female line, the

courts have decided that this cannot take place anymore.

"La transmission des titres ne se fait plus, dans le

droit moderne, que de mâle à mâle." Trib. Civ.

Falaise, 21 Fév 1959.

Under the pre-1789 regime, it was not uncommon for a M. X, owner of

a lordship called Y, to have himself called "M. X de Y" (whether or not

he was noble). It is still possible today for a French family to

have such an addition to its family name, but only on the basis of ancient,

public and continuous usage prior to the French Revolution (Angers 29 juin

1896, Dalloz 1898, 2.217).

"L'usage établi avant 1789 d'ajouter aux noms

de famille des noms de terres nobles ou de fiefs ne peut créer un

droit que s'il est estayé d'une possession ancienne publique, acceptée

par tous et régulièrement constatée. Il est

nécessaire d'ailleurs que le nom de famille précède

le nom noble. Une personne ne doit pas être admise, pour établir

son droit d'ajouter à son nom patronymique, à se prévaloir

d'une possession accidentelle et intermittente de ce nom que ses auteurs

n'ont jamais considéré que comme un titre ou une dénomination

honorifique qu'ils n'entendaient ni substituer ni incorporer à leur

nom d'origine." Angers, 12 août 1901.

The only way to acquire a title is to inherit it according to its original

rules of transmission. In particular, it cannot be acquired prescriptively

by usage.

"si le titre nobiliaire suit, en général,

les règles du nom patronymique, il ne s'acquiert pas, comme lui,

par

le simple usage, même prolongé; il lui faut, à l'origine,

une investiture émanant de l'autorité souveraine" Civ. 11

mai 1948, Dalloz 1948 335.

Verification of Titles: the "Conseil du Sceau

des Titres"

Establishing the right to a title can only be done by a branch of

the executive. The courts cannot establish the right to a title (but

they can protect it).

"L'autorité judiciaire est incompétente

pour reconnaître ou dénier à une personne le droit

de porter un titre nobiliaire." Angers, 28 juin 1896. Dalloz 1898,

2.217

The basic principle behind all this is the French version of the separation

of powers. Titles of nobility essentially arise from the exercise of the

sovereign's prerogative; and, in that respect, the executive branch (as

represented by the ministry of Justice) is the heir of sovereigns past.

So questions arising over the meaning and intent of these sovereign acts

should be resolved by the sovereign or his modern equivalent. There

is appeal from such decisions to the administrative courts only to ensure

that the executive branch has acted coherently and in conformity with its

own rules, but the ordinary courts have nothing to say because this is

not a matter of justice, but a matter of grace, so to speak.

The agency in charge of this was originally the Conseil du Sceau

des Titres, created by Napoleon in 1808. At the time, its purpose

was to advise the sovereign on requests to create a majorat, the landed endowment

to which Napoleon's hereditary titles were attached, and to supervise their

administration. In particular,

it delivered all letters patent related to nobiliary titles.

(See the article on Napoleonic nobility and

on majorats). When the monarchy was restored

in 1814, it replaced the conseil du Sceau des titres with a commission

du sceau at the ministry of Justice,staffed by high-ranking civil servants

and chaired by the Minister of Justice as Keeper of the Seals (ord. 15

July 1814). Later, this commission was abolished, its offices formed

the division du sceau in the ministry of justice, and its decision-making

powers transferred to the conseil d'administration of the ministry (ord.

31 Oct 1830). The conseil du sceau as a separate entity

was recreated by Napoleon III (decree 8 Jan 1859). At that time,

however, majorats had been abolished (in 1835), so the functions could

not be the same. Instead, the decree

of 1859 therefore made changes to its purpose. It gave the conseil

two functions:

-

to advise the sovereign on requests for grants, confirmations or recognition

of titles (demandes en collation, confirmation et reconnaissance de

titres), final decision resting with the sovereign;

-

to "verify" any title upon request by any citizen.

Finally, the conseil was again and finally abolished on Jan 10, 1872, and

its offices and functions transferred to the ministry of Justice as in

1830. This is the current situation.

Since an administrative decision taken in 1875 by the president of the

Republic to cease grants, confirmations and recognitions, the first activity

set out in the decree of 1859 is not exercised. The second activity,

however, remains.

To verify claim to a title, one must therefore contact the Conseil

d'administration du ministère de la Justice, and present evidence

relating to the creation of the title in full accordance with the laws

in force at the time of creation (before 1789: the king, by letters patent;

1808-1815: by Imperial decree; 1815-1848: by Royal letters patent; 1852-1870:

by Imperial decree; 1871-77: by presidential decree) and proof that he

is the individual designated by the applicable rules of transmission to

bear the title at present. The office in charge was until 1947 the

"bureau du sceau de France"; since then, the office has changed within

the ministry of justice. At present, the "bureau du droit civil général",

an office in the sous-direction

de la législation civile, de la nationalité et de la procédure

carries out the duties (direction des affaires civiles et du sceau - Sceau

de France; 13 Place Vendôme 75 042 Paris, France).

It prepares a report to the conseil, which then transmits its

opinion to the Minister of Justice, who may then issue an arrêt

authorizing

the inscription of the individual on the Registre du Sceau (at a

cost of 2000F). The individual can then use this document to obtain insertion

of his title on any legal document, including birth certificate, identity

card, passport, etc. The procedure must be repeated at every generation,

because the arrêt

is valid ad personam.

This procedure is necessary in order to establish a claim beyond doubt.

It does not mean that the right to a title does not exist until such time.

Nor does it mean that the legal consequences of a right to a title cannot

be sought in ordinary courts or from certain government officials.

In fact, there is ample jurisprudence

to show that one can obtain the insertion of a title in the registry of

the Etat civil or defend a title against usurpation based on a court decision

alone, without verification by the conseil (see the cases cited

in the note Pr. André Ponsard, Répertoire Dalloz 1958

283). Since an administrative memorandum of the interior ministry

of 1966, however, officers of the Etat civil are instructed to refuse insertion

of titles in birth, marriage and death registrations without a verification.

There is no legal basis for that decision.

All confirmations of titles can be found:

-

from 1830 to 1908

-

Révérend, Albert, vicomte: Titres et confirmations de

titres: monarchie de juillet, seconde République, Second Empire,

Troisième République. Paris, 1908 (2 vol.; reprint Paris,

1974, 1 vol.).

-

from 1908 to 1958

-

Descheemaeker, Jacques: Les titres de noblesse en France et dans les

pays Étrangers; Paris, 1958, Les Cahiers Nobles.

-

from 1958 to 1987

-

Texier, Alain: Qu'est-ce que la noblesse?; Paris, 1987, pp. 407-10.

From 1872 to 1992, 407 arrêts

were issued (190 since 1908).

From 1958 to 1987 there have been 53, roughly twice a year on average.

If one counts about a thousand titles in existence and an average of 35

years between generations, then this means that only about 6% of those

who could ask for a confirmation of title do so. This is small, but

not negligible.

Disputes over Titles in Civil Courts

Two separate jurisdictions exist, civil courts and administrative courts.

The jurisprudence has established that civil courts can only draw the legal

consequences of a title recognized by the Conseil and uncontested.

"Les tribunaux de l'ordre judiciaire sont incompétents

pour connaître de contestations entre particuliers sur l'existence

et la sincérité de titres nobiliaires; ils ne sont compétents

que pour tirer les conséquences juridiques des titres nobiliaires

dûment reconnus par les autorités compétentes ou non

contestés." Cour de Cassation, 17 Nov 1891. Sirey 1893, 1.25.

For example, it can require inclusion of the title on a birth certificate

(in 1910, the duc de Rivoli got the courts to allow the inclusion of the

title "comte de Rivoli" on the birth certificate of his son). It can protect

the title from usurpation (in 1898, a duc de Montebello sued a partnership

formed by his uncles for use of his name and arms on wine labels; in 1936,

the duc de Noailles sued his nephew to prevent him from using the title

of marquis de Noailles). However, if the dispute is over the title itself:

the validity, the meaning or the applicability of the acts which created

or confirmed the title, then the administrative authority (the Conseil

d'administration) has full authority, with appeal to the administrative

court of Paris and then to the Conseil d'État, which is the

administrative supreme court. Thus, the Conseil d'État has the final

word on titles.

Disputes over titles were not uncommon in the late 19th century, but

are now rather rare. Recent examples include the complex case of baron

d'Huart in 1983 (Conseil d'Etat, Feb. 25, 1983) and the famous case

of the title of duc d'Anjou (Paris court of appeals, Nov. 22, 1989).

Usurpation of Titles and Criminal Law

Usurping a title exposes one to civil suits by the injured parties.

But it also is a breach of criminal law, which can result in a suit in

criminal courts, either brought by the public prosecutor, or more commonly

by an aggrieved private party (partie civile dans une action publique).

The case is then usually brought before a criminal court.

The 1810 edition of the Penal Code included article 259 which stated:

"Toute personne qui aura publiquement porté un costume, un uniforme

ou une décoration qui ne lui appartiendrait pas, ou qui se sera

attribué sans droit un titre impérial qui ne lui aurait pas

été légalement conféré, sera punie d'un

emprisonnement de six mois à deux ans et d'une amende de 500 à

5000F." The article was dropped in 1832. It took a law of 28

May 1858 to revive it and it remained in the Penal Code until 1993,

in the following form:

"Art. 259.§3. Sera puni d'une amende de 1800F à

60000F, quiconque, sans droit et en vue de s'attribuer une distinction

honorifique, aura publiquement pris un titre, changé, altéré

ou modifié le nom que lui assignent les actes de l'état civil."

According to the jurisprudence, this article did not only punish those

who usurp a nobiliary title but also those who, by modifying their family

name, try to give it an honorific appearance. The use of a "particule"

and of a famous name necessarily fall into that category.

"les prévenus avaient pour but, par ostentation,

de s'attribuer, à la faveur d'une équivoque, l'apparence

de la noblesse [...] l'article 259 du code pénal ne punissant pas

seulement ceux qui prennent sans droit un titre proprement dit, mais aussi

ceux qui, par une altération ou une modification de leur nom patronymique,

entendent lui imprimer une apparence honorifique." (Cour de Cassation,

ch. criminelles, 14 janv. 1959; Gazette du Palais 1959 1.220)

"l'adjonction, sans droit, d'une particule et d'un nom

illustre caractérise nécessairement le but d'acquérir

une distinction honorifique" (Cour de Cassation, ch. criminelles, 14 févr.

1957; Gazette du Palais 1957 1.353)

The usurpation had to be public: this publicity could result from the use

of the usurped title in all social and commercial intercourse. The

usurpation had to be intentional: the intention could be evidenced by the refusal

to desist when warned.

"[... les prévenus] n'ont cessé depuis

lors de l'utiliser [le nom] dans tous les actes de leur vie sociale, commerciale

et mondaine [...] il s'ensuit de là que la publicité de l'usurpation

a été constatée [...]

la persistance des prévenus à faire usage

de ce nom, malgré les invitations, et en dépit même

d'une mise en demeure notifiée le …, établit qu'ils n'étaient

pas de bonne foi" (Cour de Cassation, ch. criminelles, 14 janv. 1959; Gazette

du Palais 1959 1.220)

There was in fact a fair amount of precedent in the matter: case of a

man who called himself d'Aigueperce; case of a man who added the name of

his wife to his own, misspelling it so as to add a particule; case of a

man who had added the particule to his name on his doorplate and in the

marriage contract of his daughter; case of a man who had added a particule

to his name while registering a company (see Répertoire général,

code pénal).

In 1936, a certain Philippe Dissandes de la Villatte claimed to be "duc

de Saint-Simon" (a title he claimed to be Montenegrin), wore a number of

decorations (including St. George of Burgundy) and went around in public

in a uniform of Italian general. He received a suspended sentence

of 8 days of jail and a fine of 500F (Trib. correct. de la Seine, 9 déc.

1936; Recueil Sirey 1937, 2.133).

The present form of the law in the Penal Code (since 1993, except for the conversion

of francs to euros) is as follows:

"Article 433-17. L'usage, sans droit, d'un titre attaché à une

profession réglementée par l'autorité publique ou d'un diplôme

officiel ou d'une qualité dont les conditions d'attribution sont fixées

par l'autorité publique est puni d'un an d'emprisonnement et de 15000 euros d'amende.

Article 433-19. Est puni de six mois d'emprisonnement et de 7500 euros

d'amende le fait, dans un acte public ou authentique ou dans un document administratif

destiné à l'autorité publique et hors les cas où la réglementation en

vigueur autorise à souscrire ces actes ou documents sous un état civil d'emprunt :

- De prendre un nom ou un accessoire du nom autre que celui assigné par l'état civil ;

- De changer, altérer ou modifier le nom ou l'accessoire du nom assigné par l'état civil.

"

Legal Standing

A civil or criminal suit can be brought by the rightful bearer of the title,

whether or not his title has been verified by the conseil du sceau

or its equivalent. It can also be brought by his widow, and by all

the bearers of the name corresponding to the title, or generally anyone

in whose "familial patrimony" the name falls (see references in the note

to Cour d'Appel de Paris, 5 Dec 1962 Dalloz 1963 168).

Can titles be bought today?

No. See more details here.

Recognition of Nobility

As should be clear by now, there is no nobility in France, therefore there

is no way to authenticate one's noble status.

However, there exists a prestigious private institution that can certify

one's descent from noble ancestors by virtue of the original rules of transmission

of nobility (ascendance noble). The Association de la Noblesse

Française (ANF) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1932

and "reconnue d'utilité publique" in 1967. Its current president

is the marquis de Vogüé. It has about 2,000 families on its

roster, about two thirds of the eligible number of families. Its committee

on proofs applies criteria very strictly. The only eligible members are

those who would be noble under the rules of the Old Regime or the regimes

that followed and recognized nobility.

A.N.F.

9, rue Richepanse

75008 Paris

France

Ph: +33 1 42 60 15 06

Fax: +33 1 40 20 07 20

- The French National Archives have an online database that includes:

- appointments to offices from 1730 to 1790

- titles, ennoblements, grants of arms from Nov 1830 to May 1853

- files on members of the Legion of Honor deceased before 1954

Bibliography

See also John DuLong's excellent Bibliography

for Tracing French Noble Families.

For a good contemporary treatise on nobility, see:

There are several modern works on the subject, among which:

-

Puy de Clinchamps, Philippe du: La Noblesse. (Que Sais-je 830).

Paris: PUF, 1960. Succinct, but good introduction.

-

Texier, Alian: Qu'est-ce que la noblesse? Éditions Tallandier:

Paris, 1988. 601 p. with bibliographies, lexicon, index. Extremely detailed

study of French nobility, both historical and present, from the legal point

of view. Complete listing of relevant laws and court cases since 1789.

Highly

recommended.

There are several armories and dictionaries of contemporary French nobility.

A private institution, the Association d'Entraide de la Noblesse Française

(ANF),

was created in 1932 to keep tabs on who is of noble origin and who isn't.

It is a private, non-profit organization. Its statutes include specific

requirements to be a member, namely to be descended (in male line) from

an individual who was noble under the applicable laws when there was such

a thing as nobility in France (i.e. being a descendant of confirmed noble

or ennobled by a sovereign etc...). The ANF publishes an Annuaire or directory.

Séréville and Saint-Simon, which uses ANF data, is an excellent

dictionary, with arms, dates and some discussion of family history when

warranted. Valette lists only names, arms and numbers of male members.

Woëlmont de Brumagne is a solid, thorough work. Jougla de Morenas

is a major comprehensive armory, the best to date for France, and contains

many genealogical notices on families; furthermore, it lists sources, and

is therefore a necessary starting point. D'Izarny-Gargas, Lartigue and

Vaulchier is a recent work that I have not seen myself, but appears to

be extremely solid and thoroughly researched.

Furthermore, a large number of regional armories have been published

in the 19th and 20th c., of varying quality. See the annotated

bibliography.

-

D'Izarny-Gargas, Jean-Jacques Lartigue and Jean de Vaulchier: Le Nouveau

Nobiliaire De France. Éditions Mémoires et Documents:

Versailles, 1997. (Vol. 1: A-D, Vol. 2: E-L). A thorough listing of individuals

whose nobility (grant or confirmation) is documented, with references to

the original sources.

-

Séréville, E. de and F. de Saint-Simon :Dictionnaire de

la noblesse française. Paris, 1976; Société française

au XXe siècle, diffusion exclusive, S.E.C. (1214 pp., in-16). Supplement

published in in 1977 (Editions Contrepoint, 1977, 666pp.). The best resource

on current French nobility.

-

Valette, Régis: Catalogue de la noblesse française contemporaine.

Paris, Les Cahiers Nobles, 1959. New edition, Paris, 1977; Laffont. Revised

edition 1994. A catalogue, more summary than Séréville and

Saint-Simon, but provides a count of male members for each family, as well

as a listing by province and a listing of the nobility of each province

as of 1789.

-

Recueil des personnes ayant fait leurs preuves de noblesse devant les

assemblées générales de l'Association d'entraide de

la noblesse française.

-

Du Puy de Clinchamps, Philippe: L'Ancienne Noblesse en 1955. Paris,

1955.

-

Woëlmont, Henri de: La noblesse française subsistante :

recherches en vue d'un nobilaire moderne. Paris : H. Champion, 1928-

-

Jougla de Morenas, Henri: Grand Armorial de France. Paris: Les Éditions

Héraldiques, 1934-49.

-

Bachelin, Antoine Bachelin-Deflorenne: État présent de

la noblesse française, contenant le dictionnaire de la noblesse

contemporaine. Paris, 1873.

Not finding a name in the ANF Annuaire, Séréville & Saint-Simon

or Valette does not mean that the family is not of noble origin: they are

not complete works. If you suspect a family is claiming noble ancestry

without good reason, check:

-

Dioudonnat, Pierre-Marie: Encyclopédie de la fausse noblesse

et de la noblesse d'apparence. Paris, Sedopols, 1976-79 (2 vols.).

Reprinted in 1, 1982.

To research genealogies up to the 18th century, besides Jougla de Morenas,

the best references are the following:

-

La Chesnaye-Desbois, François-Alexandre-Aubert de: Dictionnaire

de la noblesse. Paris, 1863-76; Schlesinger. Reprint: Paris 1980, Berger-Levrault.[original

edition 1767]

-

Anselme, Père: Histoire généalogique et chronologique

de la Maison de France. Paris, 1967; Éditions du Palais-Royal.[original

edition 1726-33; reprinted 1868-90 and continued for the 19th century by

Pol Potier de Courcy].

-

Courcelles, Jean Baptiste Pierre Jullien de: Histoire généalogique

et héraldique des pairs de France, des grands dignitaires de la

couronne, des principales familles nobles du royaume, et des maisons princières

de l'Europe, précédée de la généalogie

de la maison de France. Paris, L'auteur, 1822-33.

-

Chaix d'Est-Ange, Gustave: Dictionnaire des familles françaises:

anciennes ou notables à la fin du XIXe siecle. Paris : Editions

Vendôme, 1983. [original 1903].

The Almanach de Gotha until 1938 kept track of French ducal families,

whether of Old Regime, Napoleonic or Restoration origin. For an update

since 1940, see:

-

Cuny, Hubert and Nicole Dreneau: Le Gotha français : état

présent des familles ducales et princières depuis 1940.

Paris, 1989; l'interm,édiaire des curieux.

A very useful book for French genealogy in general is the following:

-

Arnaud, Étienne: Répertoire de généalogies

françaises imprimées. Paris, 1986; Berger-Levraut.

It lists all known genealogies in print, whether monographs or as part

of collections or dictionaries. There is also a newsgroup devoted to French

genealogy, soc.genealogy.french.

Dominique Labarre de Raillicourt has published a number of monographs

that look at specific questions of contemporary French nobility: the titles

of dukes and princes, marquis, counts, viscounts, barons, regular titles

and courtesy titles, French members of the papal nobility, families whose

members were admitted to military schools before the Revolution, families

in which three consecutive members were awarded the Legion of Honor (and

thereby gained nobility under Napoleonic law). All his books are published

by himself.

-

Princes et ducs français contemporains et étrangers possesseurs

de titres français princiers et ducaux et princes et ducs étrangers

habitués en France : listes-notices-armorial. Paris, 1962.

-

Armorial des marquis français contemporains. Paris, 1965.

-

Les Comtes français contemporains; titres réguliers.

Paris, 1963.

-

Les Titres de Cour au XVIIIe siecle. Les Comtes, essai. Paris, 1968-9.

-

Armorial des vicomtes français contemporains. Paris, 1964.

-

Titres réguliers des barons français contemporains.

Paris, 1964-67.

-

La noblesse française titrée. Paris, 1970.

-

La noblesse française titrée par l'usage. Paris, 1974.

-

Les Comtes du Pape en France, XVIe-XXe siècles. Paris, 1965-67.

-

Armorial des gentilshommes des Écoles royales militaires.

Paris, 1967.

-

Légion d'honneur, anciens honneurs héréditaires

... essai de répertoire. Paris, 1966.

For 19th century titles and armory (Napoleonic and Restoration), the exhaustive

reference is Révérend:

-

Révérend, Albert: Armorial du Premier Empire : titres,

majorats et armoiries concédés par Napoleon Ier. Paris

: H. Champion, 1974.

-

Révérend, Albert: Titres, anoblissements et pairies de

la Restauration, 1814-1830 Paris : H. Champion, 1974.

-

Révérend, Albert, vicomte: Titres et confirmations de

titres: monarchie de juillet, seconde République, Second Empire,

Troisième République. Paris, 1908.

-

All three titles reprinted in 1974 in 6 volumes as Familles titrées

et anoblies du 19e siècle.

-

See also the more recent Tulard, Jean: Napoléon et la noblesse

d'Empire : avec la liste complète des membres de la noblesse impériale,

1808-1815. Paris, J. Tallandier, 1989. (Tulard is a historian, specialist

of the Napoleonic period.)