Like other Tuscan cities, Florence was part of the marquessate of Tuscany, and thus under the jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Emperor. After Mathilde left her estates to the Pope in 1115, the line of local imperial representatives was broken, and the cities of Tuscany increasingly asserted their independence, although they were racked by internal strife between partisans of the Emperor (the Ghibellines) and those of the Papacy (the Guelfs). The death of Frederic II in 1250, and the destruction of his lineage in the following years, with the establishment of the French Anjou line on the throne of Sicily, ended all Ghibelline hopes in Tuscany. Florence, until then behind Lucca (11th c.) and Pisa (12th c.) in importance, rose to prominence.

The city, or Comune, was governed in republican fashion by elected officials and a legislative body, the maggior consiglio. The executive was known as the Signioria. There were continuing tensions between the upper classes of the Arte maggiori or major guilds, and the lower classes (who briefly took over in 1378-82). In the early 15th c., the struggle between aristocratic and populist factions was won by the latter, led by Cosimo de' Medici. The rule of the Medici (1434-94, 1513-27, and from 1530) was interrupted by popular revolts and restored by external force: in 1512 by the Santa Lega (Milan, Pope, Venice) and in 1530 by the Emperor.

The last expulsion of the Medici followed the sack of Rome in May 1527, when the representatives of the Medici pope Clement VII were expelled. After the reconciliation of the Emperor and the Pope, the former besieged the city in October 1529, promising to restore the Medici. The city capitulated on 12 Aug 1530 and, under the terms of the capitulation, relinquished to the Emperor the right to determine its form of government. Accordingly, in 1531, Alessandro di Medici was made "duke of the Florentine Republic". The title "dux" was used here in a sense similar to that of "dux" in Genoa or Venice, thus meaning chief executive, and not implying the existence of a duchy. After Alessandro's murder in 1536, his distant cousin Cosimo di Medici succeeded him, with the style of Illustrissimo. Siena was annexed in 1557. By papal bull of Aug. 27, 1569 the title of "Granduca nella Provincia di Toscana" was conferred on Cosimo I, who was formally crowned by the Pope in Rome on March 7, 1570 (Laetare sunday). In spite of an official protest by the Holy Roman Emperor, Florence was henceforth known as the grand-duchy of Tuscany (1569-1859).

The arms of Florence were Argent a fleur-de-lys flory gules (first mentioned in 1251, with reversed tinctures). The Commune had per pale argent and gules, the Popolo's banner was Argent a cross gules, the Reppublica was Gules a cross argent, in dexter chief an escutcheon per pale argent and gules and another argent a cross gules.

The Florentine fleur-de-lys has a peculiar shape, which is usually indicated as "flory", but not easily described. Here is a classic rendition in inlaid marble, in the typical medieval Italian shield.

The arms of the Medici were or five tortaux 2, 2 and 1 and in chief a roundel azure thereon three fleurs-de-lys or. Their arms were originally Or six tortaux 1, 2, 2 and 1, the tortaux (palli in Italian) perhaps canting arms, representing medicinal pills. The actual number of tortaux varies quite a bit, it is often 8. The tortaux in chief was changed by augmentation of honor of Louis XI of France in May 1465 (Isambert: Recueil général des anciennes lois françaises, 10:509). Interestingly, in depictions of the 16th c. and later, the tortaux are clearly shown as 3-dimensional balls, allowing in some cases for spectacular decoration. Since the 15th c., the Medici imprese included a swan with the motto semper (always), or a ring with three ostrich feathers (see for example the decoration of the chapel in the palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence).

The grand-ducal crown, which appears immediately on coins, was peculiar: it consisted of outwardly curved spikes, with a Florentine fleur-de-lys in the middle, and it was open. The grand-dukes were, in succession: Cosimo I (1569-74), Francesco I (1574-87), Ferdinando I (1587-1609), Cosimo II (1609-21), Ferdinando II (1621-70), Cosimo III (1670-1723), Gian Gastone (1723-37). Cosimo III was the first to style himself "by the grace of God" on his accession, and to use a closed form of the Tuscan crown starting in 1706.

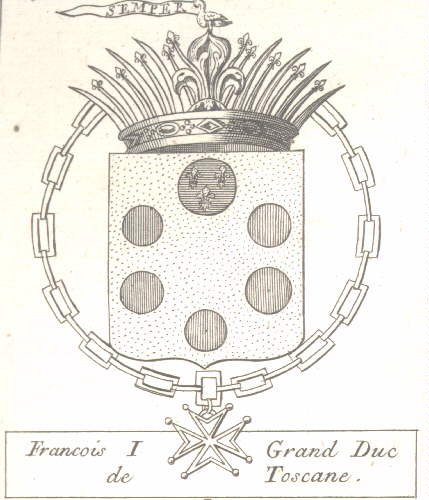

Arms of the grand-duke of Tuscany, from the Encyclopédie plates on Heraldry. Note the collar of S. Stefano, the grand-ducal crown and the motto "Semper".

It was clear in the early 18th century that the house of Medici was verging on extinction. Since it had been installed by imperial decision, and the succession was a matter of European politics, the question was settled by international treaty, and Tuscans had no say. The treaty of London, in 1718, decided that Carlos, son of Felipe V of Spain and his second wife Elizabeth Farnese, would succeed the last male heir of the Medici and receive Tuscany in fief from the Emperor. These arrangements were changed in the Treaty of Vienna of Nov 19, 1735, which recognized to Carlos the kingdom of Sicily but allocated Tuscany as compensation to François de Lorraine, husband of Maria-Teresa, who gave up his duchy to the dispossessed king of Poland Stanislas Leszcynski (father-in-law of the king of France, to whom Lorraine would return on his death in 1766).

The amazing game of musical chairs was played out as planned. Accordingly, when the last Medici died without heirs on July 9, 1737, the Emperor Charles VI conferred the grand-duchy of Tuscany on his son-in-law and his heirs male in perpetuity. As grand-duke, Francesco I used as arms Quarterly 1: Hungary and Anjou-Naples, 2: Jerusalem and Aragon, 3: Anjou and Guelders, 4: Jülich and Bar, over-all Lorraine and Tuscany. The arms are surrounded by collar of the Golden Fleece and surmounted by a standard closed royal crown (instead of the Medici crown). He was styled: Francois III by the grace of God duke of Lorraine, Bar and grand duke of Tuscany, king of Jerusalem.

On September 13, 1745 he was elected Emperor. The same shield was used, with the closed crown, but set on the breast of the Imperial double-headed eagle holding sword and scepter and surmounted with the imperial crown. The style became: "François by the grace of God Emperor of the Romans Forever August, king of Germany and Jerusalem, duke of Lorraine and Bar, Grand Duke of Tuscany."

The duchy went on his death in 1765 to his second son, Peter Leopold I (1747-92), archduke of Austria, and his male heirs, according to the terms of a Motu-Proprio of 1763. His style was: Peter Leopold, by the grace of God prince of the kingdom of Hungary and Bohemia, Archduke of Austria, Grand-Duke of Tuscany". The arms changed to Quarterly 1: Hungary ancient and modern, 2: Bohemia, 3: Burgundy ancient, 4: Bar, overall Lorraine, Austria and Tuscany, surrounded by the Golden Fleece, a cross of San Stefano behind the shield and a royal crown. The inescutcheon itself bears an archducal crown. It is also used alone, on a cross of San Stefano, as in the illustration which follows. The arms remained unchanged until 1859 (except for 1801-14).

Arms of the grand-dukes of Tuscany, from the base of a statue of Ferdinand III in Arezzo.

Leopold became king of Hungary and Bohemia at the death of his brother Joseph in 1790, whereupon two royal crowns were added to his arms and two griffons as supporters. Then, on Sep 30, 1790 he was elected emperor and his arms placed on the Imperial eagle. In 1791 he ceded Tuscany to his younger son Ferdinand III (1769-1824), who ruled until a Napoleonic interruption: the treaty of Lunéville(Feb 9, 1801) transferred Tuscany to the Bourbon-Parma family.

From 1801 to 1803, Ludovico I of Bourbon-Parma reigned as king of Etruria, styled "by the grace of God infant of Spain, king of Etruria". After his death, his son Ludovico II reigned under the regency of his mother Maria-Luisa of Bourbon, Infanta of Spain, duchess of Lucca. The state arms were: Per pale Farnese and Gonzaga, in base per pale Lorraine and Austria; en surtout Spain (quarterly Castile and Leon), en surtout-du-tout per pale Bourbon-Parma and Medici. The cross of San Stefano (a Maltese cross gules) is placed behind the shield. The crown is either a standard royal crown (on coins) or a closed version of the spiked grand-ducal crown (without the central fleur-de-lys). Ludovico I styles himself "by the grace of God infant of Spain, king of Etruria, prince of Parma and Piacenza". Maria-Luisa herself bore: Quarterly Lucca and Spain, en surtout Anjou.

By the treaty of Fontainebleau of Oct 27, 1807, Etruria was ceded to Napoleon, and it was annexed to France on March 28, 1808. Then, on March 3, 1809, it was conferred to Elisa Bonaparte, princess Bacciochi, sister of Napoleon, who bore: Quarterly, 1. Or six torteaux gules (Tuscany), 2. per fess argent and gules a panther rampant or (Lucca), 3. Gules a bend chequy of three rows argent and azure, on a chief or a double-headed eagle sable, the chief supported by a divise argent bearing a cross gules (Massa), 4. gules two bends between two stars or (Bonaparte), en surtout Azure a French imperial eagle or. She had been made princess of Piombino in March 1805 and her husband prince of Lucca in June 1805.

The treaty of Paris (May 30, 1814) returned Tuscany to Ferdinand III of Austria. He resumed the same style and arms as before 1801. The territory of the Grand-Duchy was defined by article 100 of the Act of the Congress of Vienna of 1815. He was succeeded in 1824 by his son Leopold III (1797-1870), who promulgated in 1848 a constitution suppressed in 1852, and was expelled by his subjects in 1859. The preliminary treaty of Villafranca of July 1859 between France and Austria called for his return, but the city of Florence rejected it. A referendum on March 11, 1860 gave a 95% vote in favor of union with Piedmont-Sardinia, which became effective by a decree of March 22, 1860.

Reference: Arrigo Galeotti: Le Monete del Granducato di Toscana. 1930: Livorno, Belforte & C.. Reprint 1971: Forni Editore, Bologna. [The coins are a good source for arms and styles; the text also provides information on dates and succession settlements.]

Florence used its arms as flag (at sea for the first time in 1362). By the mid-16th century, the Medici white flag with the family arms had replaced it. From 1749 to 1765 the flag was yellow with the Imperial eagle, but in 1765 a new flag was devised, three horizontal stripes red-white-red (reminiscent of the Austrian arms), with or without the grand-ducal arms, which was used until 1859 with two interruptions: from 1801 to 1807 the kingdom of Etruria used a flag with horizontal striped blue and white, 5 stripes for the national flag (with arms: per pale Bourbon and Medici, the shield laid over the cross of San Stefano) and 3 stripes for the merchant marine. Also, from 1848 to 1849 the Italian tricolor with grand-ducal arms was used. The Habsburg-Lorraine flag is presently used by Tuscan independentists (as seen on a poster calling for a referendum on independence in May 1997).

E ciò fatto, sanza contasto sì ordinarono e feciono popolo con certi nuovi ordini e statuti, e elessono capitano di popolo messer Uberto da Lucca; e fu il primo capitano di Firenze; e feciono dodici anziani di popolo, due per ciascuno sesto, i quali guidavano il popolo e consigliavano il detto capitano, e ricoglìensi nelle case della badia sopra la porta che va a santa Margherita, e tornavansi alle loro case a mangiare e a dormire: e ciò fu fatto a dì 20 d' Ottobre, gli anni di Cristo 1250. E in quello dì si diedono per lo detto capitano venti gonfaloni per lo popolo, a certi caporali partiti per compagnie d' arme e per vicinanze, e a più popoli insieme, acciocchè quando bisognasse, ciascuno dovesse trarre armato al gonfalone della sua compagnia, e poi co' detti gonfaloni trarre al detto capitano del popolo. E feciono fare una campana la quale tenea il detto capitano in su la torre del Leone, e 'l gonfalone principale del popolo ch' avea il capitano, era dimezzata bianca e vermiglia. Le 'nsegne de' detti gonfaloni erano queste: nel sesto d' Oltrarno, il primo si era, il campo vermiglio e la scala bianca; il secondo, il campo bianco con una ferza nera; il terzo, il campo azzurro iv' entro una piazza bianca, con nicchi vermigli; il quarto, il campo rosso con uno dragone verde. Nel sesto di san Piero Scheraggio, il primo, fu il campo azzurro e uno carroccio giallo, ovvero a oro; il secondo, il campo giallo con uno toro nero; il terzo, il campo bianco con uno leone rampante nero; il quarto, era pezza gagliarda, cioè a liste a traverso bianche e nere: questa era di san Pulinari. Nel sesto di Borgo, il primo era il campo giallo e una vipera, ovvero serpe verde; il secondo, il campo bianco e una aguglia nera; il terzo, il campo verde con uno cavallo isfrenato covertato a bianco e a croce rossa. Nel sesto di san Brancazio, il primo, il campo verde con uno leone naturale rampante; il secondo, il campo bianco con uno leone rampante rosso; il terzo, il campo azzurro con uno leone rampante bianco. In porte del Duomo, il primo, il campo azzurro con uno leone a oro; il secondo, il campo giallo con uno drago verde; il terzo, il campo bianco con uno leone rampante azzurro incoronato. Nel sesto di porte san Piero, il primo, il campo giallo con due chiavi rosse; il secondo, a ruote accerchiate bianche e nere; il terzo, il di sotto a vai e di sopra rosso. E come ordinò il detto popolo le 'nsegne e gonfaloni in città, così fece in contado a tutti i pivieri il suo, ch' erano novantasei, e ordinargli a leghe acciocchè l' una atasse l' altra, e venissero a città e in oste quando bisognasse.

Lib. VI, cap. 40Poich' avemo detto de' gonfaloni e insegne del popolo, è convenevole che facciamo menzione di quelle de' cavalieri e della guerra, e come i sesti andavano per ordine nell' osti. L' insegna della cavalleria del sesto d' Oltrarno era tutta bianca; quella di san Piero Scheraggio a traverso nera e gialla, e ancora oggi l' usano i cavalieri in loro sopransegne ad armeggiare; quello di Borgo addogato per lungo bianco e azzurro; quello di san Brancazio tutto vermiglio; quello di porte del Duomo era.......; quello di porte san Piero era tutto giallo. L' insegne dell' oste erano le prime del comune dimezzate bianche e vermiglie: queste aveva la podestà. Quelle della posta dell' oste e guardia del carroccio erano due, l' uno campo bianco e croce piccola rossa, l' altro per contrario campo rosso e croce bianca. Quella del mercato era.......; quelle de' balestrieri erano due, l' una il campo bianco, e l' altra vermiglio, in ciascuno il balestro; e per simile modo quello de' pavesari, l' uno gonfalone bianco col pavese vermiglio e 'l giglio bianco, e l' altro rosso col pavese bianco e 'l giglio rosso; e quegli degli arcadori l' uno bianco e l' altro rosso, iv' entro gli archi; quello della salmeria era bianco col mulo nero; e quello de' ribaldi bianco co' ribaldi dipinti in gualdana e giucando. Queste insegne de' cavalieri e dell' oste si davano sempre il dì di Pentecoste nella piazza di Mercato nuovo, e per antico così ordinate; e davansi a' nobili e popolani possenti per la podestà. I sesti quando andavano tre insieme, era ordinato, Oltrarno, Borgo, e san Brancazio, e gli altri tre insieme: e quando andavano a due sesti insieme, andava Oltrarno e san Brancazio, san Piero Scheraggio e Borgo, porte del Duomo e porte san Piero; e questo ordine fu molto antico.

E le 'nsegne delle sette arti maggiori furono queste: i giudici e notari, il campo azzurro e una stella grande ad oro: i mercatanti di Calimala, cioè de' panni franceschi, il campo rosso con una aguglia ad oro in su uno torsello bianco: i cambiatori, il campo vermiglio e fiorini d' oro iv' entro seminati: l' arte della lana, il campo vermiglio iv' entro uno montone bianco: i medici e speziali, il campo vermiglio iv' entro santa Maria col figliuolo Cristo in collo: l' arte de' setaiuoli e merciari, il campo bianco e e una porta rossa iv' entro per lo titolo di porte sante Marie: i pellicciai, l' arme a vai, e nell' uno capo uno agnus Dei in campo azzurro. L' altre cinque seguenti alle maggiori arti s' ordinarono poi quando si criò in Firenze l' uficio de' priori dell' arti, come a tempo più innanzi faremo menzione; e fu loro ordinato, per simile modo delle sette arti, gonfaloni e arme: ciò furono, i baldrigari (ciò sono mercatanti di ritaglio di panni fiorentini, calzaiuoli, e pannilini, e rigattieri) la 'nsegna bianca e vermiglia: i beccari, il campo giallo e un becco nero: i calzolai, attraverso listata bianco e nero chiamata pezza gagliarda: i maestri di pietre e di legname, il campo rosso iv' entro la sega, e la scure, e mannaia, e piccone: i fabbri e' ferraiuoli, il campo bianco e tenaglie grandi nere.