Counter-seal of Louis XIV, 1643.

(Source: Ministère de la Culture, Banques d'images ARCHIM).

The arms of France, since the late 12th century, have been Azure, a semis of fleurs-de-lis or, changed in 1376 to Azure, three fleurs-de-lis or. The medieval crown was open with fleurs-de-lys. The supporters, since about 1423 were two angels (prior to that royal seals show the arms of France surrounded by the emblems of the Evangelists). In the 16th c. the angels are shown each wearing a tabard and holding a banner with the arms of France (and later Navarre). A 1515 frontispice to the translation of Robert Gaguin's Chroniques de France shows a closed crown (hitherto only the Emperor used a closed crown), and the shield is supported by Saint Denis (in whose abbey the kings of France were buried) and Saint Remi (bishop of Reims, who baptized Clovis).

It is occasionally said that the basis for adopting a closed (imperial) crown by the king of France was the cession by Andreas Paleologue (1453-1502, nephew of the last emperor Constantine XI) of his rights to the Byzantine empire to Charles VIII, on 11 Sept. 1494 (see Mémoires de l'Académie des Inscriptions, vol. 17, p. 572; in October 1740 it was reported that the pope had given to the French ambassador to the Holy See the original of the cession, accepted in the name of Charles VIII by the cardinal of Corfu [Courrier d'Avignon, 15 Nov 1740).

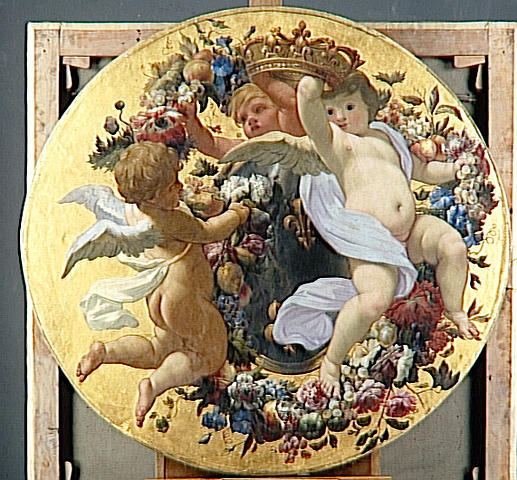

Arms of France, by Michel Dorigny, mid-17th c.

A baroque variation on the theme of angels as supporters.

(Source: Ministère de la Culture,

base de données Joconde.)

In 1469 Louis XI created the Order of Saint-Michel, and after that date the royal arms are usually shown encircled with the collar of that order. That order soon became devalued because it was awarded too easily. In 1578 Henri III created the Ordre du Saint-Esprit with a limit of 100 knights. The two orders were together known as the ordres du Roi and always encircled the royal arms.

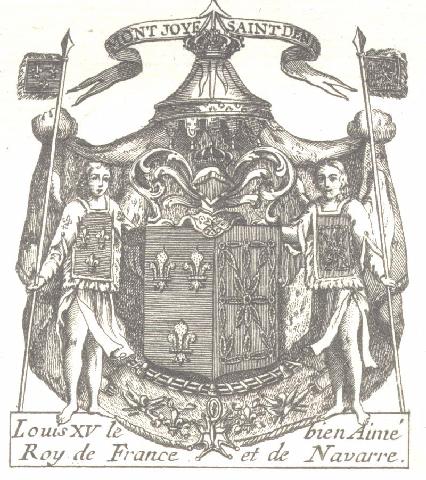

In the grand version, the shield is usually placed beneath a pavilion armoyé, with a royal crown on an open helmet on the shield and another crown on the pavilion. The cri above is Montjoye Saint-Denis (Saint-Denis was the abbey where the oriflamme was kept) and the motto below is lilia neque nent neque laborant (the lillies neither spin nor work, a quote from Luke 12:27). The medieval crest was a fleur-de-lys, but it was not used after the 16th century.

Arms of Louis XV, from Diderot's Encyclopédie (ca. 1760).

.

In 1589, when Henri, king of Navarre, ascended the throne as Henri IV of France, the arms of French kings became per pale France and Navarre, which is Gules, a cross, saltire, (double) orle of chains, all linked, or. (Note that, from 1316 to 1328, the two kingdoms were also united: French royal seals of that time show on the reverse the escutcheon of France laid over the chains of Navarre). These arms were in use until 1789, and again from 1814 to 1830.

There are some variations in the way France and Navarre were combined. French coins in the 17th century always display the arms of France only, except those struck in Navarre itself; in the 18th century, a silver coin, the écu de Navarre of 1718-19 (struck nationwide, in spite of its name) has Quarterly France and Navarre. Most gold coins show the two shields side by side.

The standard regalia of the French king were the crown (open until François Ier, closed afterwards), the scepter and the hand of justice. All three elements appear in the earliest seated figures of kings on the royal seals (11th century). They are visibly displayed in the famous portrait of Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Several kings used badges or devises (combination of a badge and a motto):

Arms of Le Havre (before 1919), with François Ier's badge.

Arms of Le Havre (before 1919), with François Ier's badge.

In February 1790 the title of Louis XVI was changed from Roi de France et de Navarre to Roi des Français. The arms became simply the fleurs-de-lis or on a field azure, and remained in use until 1792 (in spite of the abolition of coats of arms and heraldry in 1790).

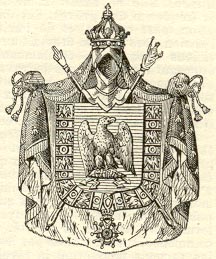

In 1804, Napoleon became emperor and (on July 20) adopted as arms Azure, an Imperial eagle or, wings inverted, guardant sinister, holding a thunderbolt in its claws on a round shield. The shield is surrounded by the Legion of Honor, with the scepter and hand of justice in saltire behind it, and an ermine-lined mantle azure with a semis of bees or around it. The crown is made of eagles as well. I do not know of a motto.

Arms of the First Empire.

Curiously, Napoleon long hesitated in his choice of emblem. After a debate with his advisers in June 1804, he chose a lion, but modified it at the last minute to an eagle. The eagle was reminiscent of Rome and Charlemagne, and strongly associated with empire, but ran the risk of confusion with the German imperial eagle, which is why a different style was adopted for the French imperial eagle. The choice of colors was not uncertain, however, since azure and or were associated with France. (See Alain Boureau: L'aigle : chronique politique d'un emblème. Paris : Éditions du Cerf, 1985.)

The bee was a favorite decorative theme, and the semy of bees used in Napoleonic heraldry, but it was not part of the official emblems. The bees were a metaphor for a Republic of equals under a single leader. It is also thought that the bee stems from ornaments found in great numbers in 1653 in the tomb of the Merovingian king Chilperic in Tournai. As decorative and heraldic elements, the bees (or on a field gules) served the same purpose as the royal fleurs-de-lys: e.g., on a chief for imperial princes, or as decoration on the staff of a maréchal d'Empire.

Napoleon III used the same arms as his uncle from 1852 to 1870.

Reverse of a 20F "napoléon", 1866.

Arms on a chimney, castle of Pierrefonds, France.

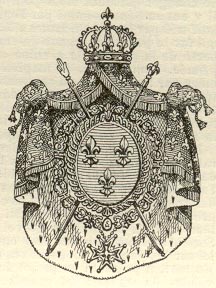

The Bourbons resumed the arms and style of kings of France and Navarre upon their return in 1814: the first official act of Louis XVIII in France, the declaration of Saint-Ouen, begins with the traditional style "Louis, par la grâce de Dieu roi de France et de Navarre." The shield of Navarre is often but not always omitted.

Arms of France, 1814-30.

In 1830, when Louis-Philippe became king of the French, he used the arms of Orléans (France differenced with a label argent) under a royal crown. The ordinance of Aug. 13, 1830 reads: Les anciens sceaux de l'Etat sont supprimés.; A l'avenir, le sceau de l'Etat représentera les armes d'Orléans surmontées de la couronne fermé, avec le sceptre et la main de justice en sautoir, et des drapeaux tricolores derrière l'écusson, et pour exergue, "Louis-Philippe Ier, Roi des Français". (Henceforth the seal of the State shall show the arms of Orleans surmounted with a closed crown, with the scepter and hand of justice in saltire and three-colored flags behind the shield, and the legend: Louis-Philippe I, king of the French").

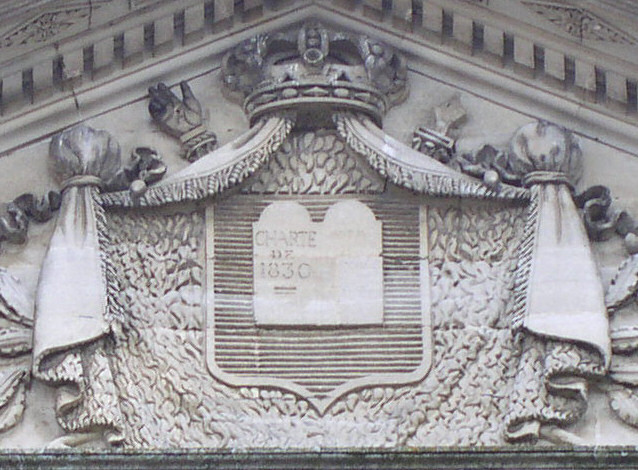

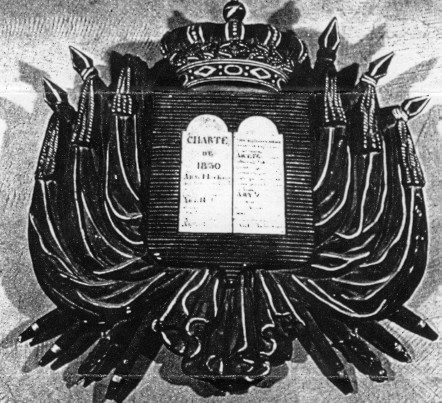

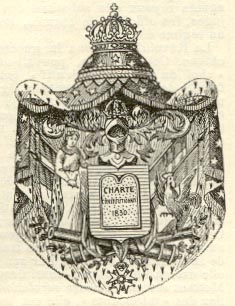

On Feb. 26, 1831, the arms were changed. The Ordonnance of that date reads: A l'avenir, le sceau de l'Etat représentera un livre ouvert portant à l'intérieur ces mots "Charte de 1830", surmonté d'une couronne fermée, avec le sceptre et la main de justice en sautoir, et des drapeaux tricolores derrière l'écusson, et pour exergue "Louis-Philippe Ier, Roi des Français". That is, an open book with the words "Charter of 1830", (the shield) surmounted by a closed crown; behind the shield, in saltire, were the scepter and hand of justice, as well as tricolor flags. Usually, the crown is depicted with leaves instead of fleurs-de-lis and the fleur-de-lis on the scepter is replaced by an orb. These arms were in use until Louis-Philippe's overthrow in 1848.

Arms of France, 1831-48. From the facade of the palais de justice, Poitiers.

Arms of France, 1831-48, as they appear at the top of a frame

surrounding a portrait of Louis-Philippe, workshop of Winterhalter.

The portrait and frame were sent in 1848 to king Kamehameha III of Hawai

and have stayed there since. (Source: Collection of the State of Hawai, The Friends of Iolani Palace. See more information).

Arms of France, 1831-48. Dictionnaire encyclopédique Larousse, 1898.

This depiction shows that the semy of

fleurs-de-lys on the mantle is replaced by stars. The supporter at dexter may

be Liberty, the supporter at sinister is a rooster. Neither seems to be

official. Artistically, this achievement is not a success.

In 1989, a ruling by the Court of Appeals of Paris stated that the arms Azure three fleurs-de-lys or were private arms, not arms of dominion, since 1830; and that no one could dispute the right to bear those arms to Don Luis-Alfonso de Borbon, duke of Anjou and present head of the house of Bourbon.

The Seal of the French Republic is not armorial. In its present form, it dates from 1848. Liberty is seated, crowned with laurel and rays of light around her head, holding a fasces with her right hand and a helm with the left hand. On the rudder, the rooster holds a globe. In front of her an urn with the letters SU recalls universal suffrage (introduced permanently in 1848 for men, in 1944 for women). Behind her, various objects symbolizing the resources and strengths of the Republic: an oak branch, a wheat garb, a plough, a lamp, a capital, a blueprint, an artist's palette. See an official description in French.

In 1905, during a visit of the king of Spain to France, an informal coat of arms for the French Republic was devised: Azure, a fasces on a laurel branch and an oak branch per saltire, bound by a scroll inscribed with the words "liberté égalité fraternité", all or. The phrase (liberty, equality, fraternity) is the motto of the French Republic and dates from the Revolution. The shield is surrounded by the collar of the Legion of Honor. These arms came into semi-official use over time, in particular in embassies (Hervé Pinoteau [3e colloque international d'héraldique, 1983], citing Ottfried Neubecker, mentions a memorandum of the ministry of Foreign Affairs to the German embassy specifying those arms in 1929). This design was adopted for official use on June 3, 1953, when it was chosen to represent the French Republic at the United Nations. But, although it can be described with a blazon, one can question to what extent it represents the coat of arms of the French Republic.

"Arms" of the French Republic since 1953.

The flags of France are discussed elsewhere.

French Presidents have used personal standards since the 2nd Republic (1848-51), which usually consists of a square-shaped tricolor flag whose white field is charged with a design. Under the 3d and 4th Republics (1875-1940, 1946-58) the design was the initials of the president. Under the 5th Republic, each president has used a particular design: the Lorraine (or patriarcal) cross gules for de Gaulle, the initials for Georges Pompidou, the fasces for Giscard d'Estaing, a tree part-oak part-olive for Mitterrand (see also the Flags of the World web-site).

Several French presidents have had to adopt arms on the occasion of their induction into the Order of the Seraphim (Sweden) or the Order of the Danebrog (Denmark). De Gaulle's arms were the French tricolor with the patriarcal cross gules, as was his standard. Giscard d'Estaing's arms were Azure, a fasces between two olive branches or. Mitterrand's arms were Azure a tree or, oak at dexter and olive at sinister. These arms thus simply incorporated the personal emblem chosen by the president. (Source: Hervé Pinoteau's latest book on the French national arms Le chaos français et ses signes : étude sur la symbolique de l'Etat français depuis la Révolution de 1789, La Roche-Rigault, 1998).

This has nothing to do with heraldry, but since I have the information, here it is.

The French monarchy did not have an anthem. (The English anthem only came into use in the mid-18th c.).

There was no anthem in the modern sense, but there was a responsory (versicle

said by the officiating priest and response by the congregation) said or sung

in Catholic churches, called the "domine fac salvum". The text comes from

Psalms 19:10 in the Vulgate:

"Domine salvum fac regem et exaudi nos in die qua invocaverimus te" (Lord save the king and hear us in the day when we shall call you).

Curiously, the King James Version is quite different: "Save, LORD: let the

king hear us when we call." However, in the Anglican liturgy, the following

responsory is used at Matins and at Evensong after the creed and the second

Paternoster and before the collects:

Priest. O Lord, save the Queen.

Answer. And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee.

This was customarily sung on Sunday at Matins in Old Regime France. There was a Gregorian plainchant for that psalm, so it's hard to call it a "royal anthem", a concept which is anachronistic anyway. Many French composers wrote motets for those verses, and there are several settings by Lully for example. The French almanach "Quid" claims that a version of this responsory composed in the late 17th c. for Mme de Maintenon later became God Save the King, but this may be the French mania to claim to have invented everything before the English.

Under Napoleon the responsory was changed to "Domine fac salvum imperatorem", and then back to "regem" in 1814, then in 1830 to "regem Philippum" (lest the Lord be confused about which king to save), then to "rem publicam" in 1848, and back to "imperatorem" in 1852. It's like changing names of streets. Charles Gounod composed a splendid march to the words for Napoleon III, which Harvard still uses, I am told, in its graduation exercises, but with "praesem nostrum" substituted, when the University president arrives.

Under the Restoration a couple tunes from light operas were used by obsequious theater managers to elicit royalist fervor in the public (the air "Ah! qu'il est bon d'etre en famille" from the light opera La Chasse d'Henri IV) but this never reached the status of an official anthem.

Under the French Bourbon monarchy, the feast days with the most dynastic significance were the Assumption (because of Louis XIII's dedication to the Virgin in the 1630s) and the feast day of Saint Louis IX on August 25. By decree of 19 Feb 1806, Napoleon I established two holidays: the feast day of Saint Napoleon on August 15 (coincidentally, the Assumption) which happened to be his birthday as well as the date of signing of the Concordate of 1802, and the anniversary of the coronation as well as the battle of Austerlitz on 2 December. On both occasions, speeches were to be made by priests and Te Deums sung, in the presence of civil and military authorities. Processions were also required on August 15. The date of 2 December is still important for some institutions linked to Napoleon: in particular, in the French Army Academy (Saint-Cyr) where it is called "2S" (each month of the school year being named after a letter in the name of the battle).