The term la Maison du Roi referred generally to the organization

and individuals "serving the king's person"; that is, providing for his

personal needs as opposed to helping him fulfill his monarchical role.

The King's Household had two major components: the civil and the military. Depending on the context, the term Maison du Roi could refer to one or the other, usually the first (the second being more often called la Maison militaire du Roi).

The information in this page comes essentially from Guyot's Traité des Droits (1784) available online at Gallica, in particular on the names and numbers of offices in various departments. I have also used Marcel Marion: Dictionnaire des Institutions de la France aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. Paris, 1923; reprint 1979.

The three forms are distinguished by the mode of tenure, that is, the way in which an individual became delegated and ceased to be delegated. The fief was a permanent form of delegation, establishing a contract between the king and his vassal, with obligations on both sides. The fief was hereditary, and its transmission subject to a body of rules. The fief was a form of property. The fief, as a delegation of royal authority, dated to the very beginnings of the Middle Ages, and by the end of the Old Regime it existed as a delegation of public authority mainly in vestigial form, as a minor aspect of titles of nobility. At the opposite, a commission was an indefinite delegation that lasted only as long as the king's pleasure; it did not create any obligations on the part of the king, and could be revoked at any time; it was not a form of property. It was a modern form of delegation of authority, and was employed for those positions that most resemble modern functions (ministers, ambassadors, administrators of provinces).

The office fell somewhere in between. Originally office-holders served at the king's pleasure, but by the late 15th century their right to serve for life, subject to good behavior, had become established. Whether it was a form of property (and if so, whether it was moveable or immoveable, that is, real or personal property) was still debated by jurists at the end of the Old Regime. It was a dignity, a station in the hierarchy of society, that carried with it the exercise of public authority or power. It was used for the kinds of positions that emerged in the later part of the Middle Ages, more specialized than the earls or dukes of the High Middle Ages: those linked to justice, police, tax collection, and the king's household.

An office was normally created by an edict, that is, a publicly proclaimed law that created the position and defined its powers and prerogatives (a commission, by contrast, was defined only in the document itself). An officer was appointed by the king or, at the lower ranks, by someone duly authorized. The form of appointment was that of letters patent, specifically letters of provision. The letters had to be registered as authentic by an appropriate court or official. The appointee was received by the king (or his delegate), and then had to be "installed", that is, accepted as suitable by the relevant college or body, after his qualifications had been verified. The officer served until death or resignation, unless malfeasance could be established through a judicial proceeding, or until the office was abolished altogether. The office was usually held in trust, meaning that the officer received wages or appointments and was accountable to the king for any income or profit, although the office could have additional fees attached to it which the officer was entitled to collect from those dealing with him.

The officer had a say in the choice of his successor: he could recommend a successor for himself (after his death or resignation). In the course of time this feature made the office seem to be a form of property which the officer could dispose of freely; Loyseau in the 17th c. thought of offices as a third category of property between real and personal, but by the 18th century jurists like Pothier saw it as real property that could be mortgaged and foreclosed. There was an active market for offices, which were advertised for sale in newspapers, and the evolution of the prices of various offices has been studied. Nevertheless, the successor always had to be approved by the king, and the legal status of some offices (whether they were a form of property) remained unclear.

What was undoubtedly the officer's property was not the office, but the finance of the office, the sum of money that the first appointee had given to the king as a form of bond for the office (usually, the wages (gages) were in fact the interest on this initial capital, not wages in the modern sense of compensation for work): this characteristic of offices is called venality and became generalized in the 16th century. Anyone succeeding an officer had to repay his predecessor the finance of the office, and the new officer became the king's creditor in lieu of the previous holder of the office (this is what "purchasing" the office meant in reality). Thus the king always owed the finance of the office as long as that office existed, and if he wanted to abolish the office he had to repay the finance to the current office-holder. In the late Old Regime, the creation of offices became a common means of raising revenue for the king. As Pontchartrain (minister of Louis XIV) put it, each time it pleased the king to create an office, it pleased God to create a dimwit to buy it. By the 1660s, there were over 45,000 offices in France (for a population of no more than 20 million). Efforts were made to reduce these numbers, but they grew again during the wars of Louis XIV, especially the War of Spanish Succession. The venality of offices was abolished in 1789 and most officers were reimbursed. But Napoleon and Louis XVIII after him recreated a few venal offices, some of which existed until very recently (auctioneers, or commissaires-priseurs) and others still exist (huissiers).

The officers and servants of the king who were listed by name on the wage-rolls of the King's Household (rolls registered every year in the Cour des Aides) were generally known as commensaux du roi and as such were entitled to special privileges. There were three classes: the great officers of the crown and great officers of the king formed the first, servants formed the third. The second class was entitled to the rank of écuyer (esquire, the lowest grade of the nobility). Generally, the commensaux were exempt from a number of taxes and obligations, most notably from the taille (a tax levied on commoners), the aides (excise taxes on wines and spirits), the franc fief (frank fee, a transfer tax paid by non-nobles on noble fiefs they bought or sold), various tolls, the obligation of billetting, etc. One important privilege was the right of committimus, which allowed the commensaux to have any civil suit in which they were plaintiffs or defendants tried before the Prévôté de l'Hôtel, a special court attached to the king's household with jurisdiction within a circle of 10 leagues around the king's court (wherever that might be located), instead of the normal courts. These privileges lasted only as long as the position was held and were neither lifelong nor inheritable.

Many offices were exercised by quarter: for the same position, four people were appointed, but only one was on duty at any time. They usually alternated by quarter.

The Grand Aumônier was originally the cleric in charge of administering the king's alms, as his name indicates. Around 1550 he acquired the functions previously held by the arch-chaplain, and became head of the ecclesiastical part of the king's household.

He was the pastor of the king and the bishop of the court, wherever it might be locatged. He could be present for the king's morning and evening prayers, and at the king's meals for saying grace. He gave the king the sacraments, baptized his children, married the royal princes, held the Gospels for the king whenever he took a solemn oath, dispatched the oaths of loyalty to the king of all bishops.

Among his privileges were: membership ex officio in the Order of the Saint-Esprit, administration of the hospital called Quinze-Vingts in Paris (until 1671 he also supervised all leprosy houses and other hospitals), and until 1621 supervision of all abbeys and convents in France. At the king's death he received the silverware of the king's chapel.

He received 1200L in gages, a 1200L pension, 6000L plat et livrée, 6000L as member of the Order of the Saint-Esprit.

The position was held in the 17th and 18th c. by members of the high nobility, oftentimes cardinals. They did not perform the actual tasks of the office except on the most solemn occasions, and were replaced in all duties by the Premier aumônier, the 2d-ranking member of the ecclesiastical household. He received 1200L in gages, 3000L pension, 6000L plate et livrée.

The 3d ranking cleric in the Household was the maître de l'oratoire (Master of the Oratory), although he had no role by the end of the 18th c. The position was created in 1523 by François Ier to head the chaplains of the Oratory (see below). His powers were transferred in 1671 to the Great Almoner, but the position survived. He received 120 livres + 3600 livres pour ses liveries and his bouche à cour (bouche of court, an allowance given to officers required to live at court).

The 4th ranking cleric was the Confesseur du Roi (king's confessor).

Prédicateur du Roi (king's preacher)

The rest of the clerical household consisted of aumôniers, chapelains (chaplains) and clercs de chapelle (chapel clerics).

The aumôniers par quartier, of which two were on duty in any quarter of the year (there were 8 in total), were the ones actually carrying out the duties of the Great Almoner and the First Almoner on a daily basis in the presence of the king, for his prayers, his meals, and at mass. Every fortnight one of the almoners served the king while the other served the Dauphin or some other royal prince.

The chaplains and clerics performed the mass service. They were divided into two bodies:

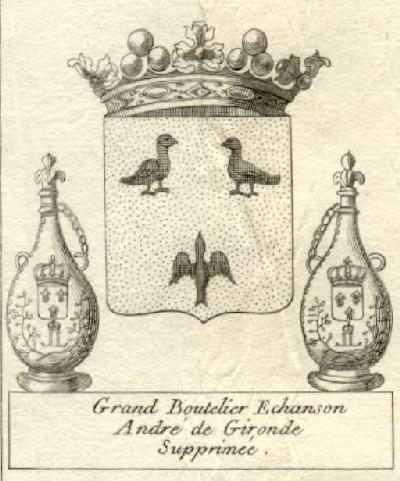

Three offices of the household remained in the 18th century as purely ceremonial, performing only at the banquet following coronations:

At the coronation banquet, once the king gave the order for the meal, the grand maître went to the kitchen and came back to inform the king that the table was set. The panetier went to the gobelet (buttery) and brought back the cadenat (pictured in his coat of arms) containing the king's napkins; the échanson carried the soucoupe, glasses and flasks (pictured in his coat of arms); the tranchant (carver) carried the knife, fork and spoon (knife and fork were shown in saltire behind his coat of arms). During the meal, the three were placed in front of the king's table while the grand maître stood at the king's right. The panetier changed the king's napkins and plates, the échanson served him wine, and the tranchant brought and took away the dishes.

In the Middle Ages, their offices held some jurisdiction over the trades connected to their functions: e.g., the panetier over breadmakers, the échanson over wine-sellers, etc.

The next-ranking officer was the Premier Maître d'hôtel (Master of the Household), who actually ran the seven departments under the grand maître. He brought the king's bouillon in the morning and took the orders relative to meals for the day, handed him his napkin after taking communion at mass. When unavailable, he was replaced by the Maître d'hôtel ordinaire.

The actual work on a daily basis was carried out by the maîtres d'hôtel par quartier and the 36 gentilshommes servants (18 after 1780). Specifically, the officers of the gobelet, preceded by a huissier and accompanied by a guard, brought the king's nef and couvert, which the gentilshommes servants set on the table. The courses were brought by two guards, the huissier, the maître d'hôtel, a contrôleur clerc d'office, the gentilhomme servant-panetier, the écuyer de cuisine, the garde-vaisselle, and two guards. The gentilhommes servants performed exactly the same functions as the panetier, échanson, and tranchant at the coronation banquet.

Lesser-ranking officers (not entitled to the style of "esquire") performed other functions. Flatware was kept by a garde-vaisselle, tables were carried by porte-tables, and serdeaux received the dishes from the gentilhommes servants. At the doors of the dining room stood the huissiers de salle (ushers), who also relayed orders to the kitchens. There were 12, a number reduced to 6 in 1780.

In the kitchens, there were:

In the Middle Ages, the great officers of state had attempted to

turn their office into a hereditary fief, and the chamberlain was the only

one who had succeeded. As a resulty, the function had split between

the chambrier, who held his position as a hereditary fief, including

the jurisdiction (over a number of crafts and trades related to clothing)

and the annual rents attached to it; and the chambellan, who performed

the actual duties, and received the incidental fees owed to the office.

The fief of the grande-chambrerie had become hereditary in the house of

Bourbon since 1397, was confiscated along with the other possessions of

the duc de Bourbon in 1527, and given to the king's younger son the duc

d'Orléans, at whose death in 1545 it was united to the crown.

Thus, only the chambellan remained, but his attempts to regain the jurisdiction

and rights of the chambrier (especially in 1622) were rebuffed by Parlement.

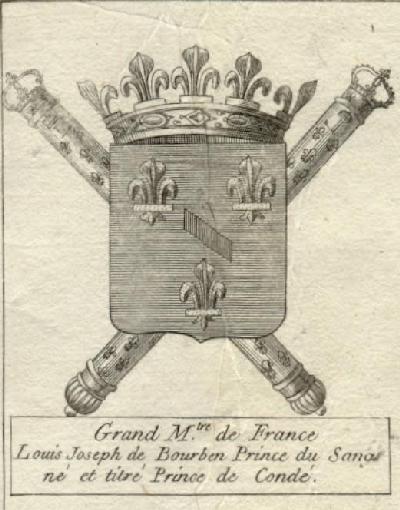

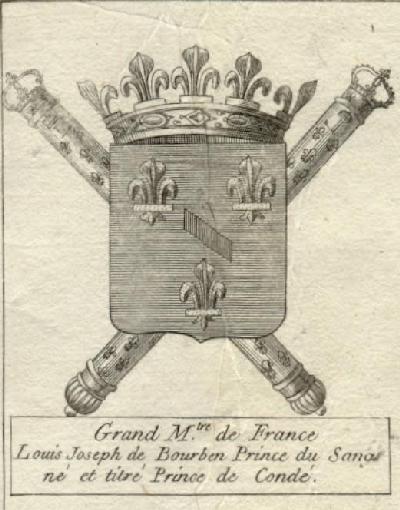

The grand-chambellan was one of the Great Officers of the Crown, along with the constable, the chancelor, the stewart (grand-maître), the admiral and the marshals of France (letters patent of 3 Apr 1582). He played a particular role during the coronation ceremonies and the ensuing banquet. His mark of office was the royal banner, which he deposited in the king's tomb at his master's funeral. His prerogative is to assist in the king's rising every morning and hand him his shirt, an honor otherwise reserved to royal princes; if the king dines in his room, the chambellan serves him. During parliamentary ceremonies such as a lit de justice, he sits at the king's feet. In solemn entrances he rode to the right of the king, the head of his horse level with the king's leg. He took the oath of the officers in his department.

The office of Gentilhomme de la Chambre (gentleman of the bedchamber) was created after the abolition of that of chambrier. There was initially one, increased to two and three by Henri IV, and finally to four by Louis XIII, each serving for a full year. He performs the duties of the grand-chambellan in his absence. He receives the oaths of the officers of the bedchamber, is in charge of funeral ceremonies, oversees the king's entertainments and supervises the two main theater companies in Paris (Comédie française and Comédie italienne). They each receive 3,500L in wages, 4,500L in pension, and 6,000L in other fees.

Under the nominal supervision of the grand chambellan, and the practical control of the gentilhomme de la chambre, came several departments, all related to the king's bed, clothing, health, and entertainment:

The Premiers valets de chambre (there were four) served by quarters. The serving first groom performed the duties of the chamberlain or the gentleman of the bedchamber in their absence. He slept in the king's bedroom and rose one hour before the appointed time for the king's rising, and went out to dress in the antechamber. Shortly before the appointed time he and his servants (garçons de la chambre, 6) went in and opened the shutters, and removed the groom's folding bed, while another servant warns the chamberlain. Once the king is awakened the kitchen is ordered to serve the breakfast, and an usher stands at the door, allowing only authorized persons (those who have the entrées familières). The king then calls the grande entrée, at which point another cast of characters enters: the officers of the household, and those granted the privilege. The chamberlain, or in his absence the gentleman of the bedchamber, or in his absence the first groom, hands the king his robe, and later his shirt. At night, the first groom undoes the king's garters, pulls the drapes of the king's bed, and locks the door of the bedroom from the inside.

The valets de chambre ordinaires (there were 32) served by quarters, helped in dressing and undressing the king, holding his mirror, giving him a chair, etc. During the day, one of them kept the king's bed. They were all deemed noble and thus enjoyed the style of esquire as long as they were in office, or after 25 years in service.

Other valets de chambre included the barbiers (8), tapissiers (4), horlogers (8), all serving by quarters. The barbiers combed and shaved the king, the horlogers took care of the time-pieces, the tapissiers prepared the bed.

The king had pages de la chambre, pages de la grande écurie, pages de la petite écurie. There were two huissiers de l'antichambre (ushers of the antechamber) who took position 30 minutes before the king awakened and the first person they let in was the gentleman of the bedchamber. The huissiers de la chambre numbered 16, serving by quarters. They took charge of the doors of the bedroom and upon orders transmitted by the gentleman, allowed people in. They kept order and quiet in the bedroom, making sure no one covered their heads or sat on the furniture. The huissiers de cabinet (ushers of the cabinet, 2) kept the doors of the king's cabinet where he worked.

Other officers: the porte-manteaux (1 ordinaire, 12 serving by quarters) held the king's hat, gloves and cane, coat, and in certain circumstances his sword; the porte-arquebuses (groom of the crossbows) carried his firearms when he went shooting. The chamberlain's department also included 9 porte-meubles, 2 porte-chaises, 1 menuisier, 1 capitaine des levrettes de la chambre, 1 capitaine de l'équipage des mulets, (in charge of the king's mules which transported furniture when the king moved around); 1 peintre de la chambre et du cabinet, 1 graveur et dessinateur du cabinet du Roi, 1 dessinateur ordinaire de la chambre et du cabinet, 1 imprimeur ordinaire de la chambre et du cabinet.

The two maîtres de la Garde-robe (masters of the robe) existed long before the grand-maître. They hand the king in the morning his cravate (necktie), mouchoir (handkerchief), gants (gloves), chapeau (hat); in the evening they remove the justau-corps, veste, cordon bleu, cravate.

Assisting them were several grades of valets de la garde-robe (groom of the stole). There were 4 premier valets de la garde-robe, serving by quarter. The serving premier valet helps the grand-maître or the maître dress and undress the king, and fulfills their functions of in their absence. The valet de garde-robe ordinaire and 16 quarterly valets de garde-robe brought the king's clothes and helped remove his boots or shoes. All valets were styled écuyer and enjoyed the same privileges as the valets de chambre du Roi.

There are also 4 garçons de garde-robe who take care of the king's clothes, a porte-malle, who carried a suitcase with the king's clothes on horseback whenever the king goes out (except for hunting). The cravatier was in charge of the king's neckties, cuffs and other lace; he also affixed diamonds and cufflinks. These officers also had the style of écuyer and rank of commenseaux.

There were furthermore 1 tailleur ordinaire, 1 garçon tailleur, 1 chapelier ordinaire, and 3 coffretiers-malletiers-gainiers.

The garde-meuble de la Couronne was a department within the garde-robe, in charge of the moveable property and furniture of the king.

The head of this group was the premier médecin du Roi, who took his oath directly from the king. The office conferred hereditary nobility and the personal rank of count. He also had wide supervisory powers over all physicians in the kingdom. Below him were 1 premier médecin ordinaire, 8 médecins ordinaires serving by quarter, 1 médecin du Roi, 8 médecins consultants, 1 médecin oculiste and 1 médecin ordinaire de la Maison du Roi.

The premier médecin entered the king's bedroom at the entrées familières, whereas the premier médecin ordinaire only entered at the so-called première entrée (which was really the third, after the grandes entrées). The physicians' role was obviously important when the king was taken ill.

The king had a number of surgeons: 1 premier chirurgien, 1 premier chirurgien ordinaire, 8 chirurgiens serving by quarters, 4 chirurgiens-renoueurs ordinaires, 1 chirurgien-oculiste, 1 chirurgien-dentiste, 2 opérateurs pour la pierre, 1 chirurgien-pédicure. The surgeons were required to remain close to the king when he went hunting or on a military campaign.

There were 8 apothicaires, 4 of which were called chefs and 4 were called aides; they served by quarters.

The musique du Roi was comprised of 2 surintendants de la musique (6000L), 4 maîtres de la musique (3000L; previous positions of sous-maîtres were abolished). The musicians were still under the authority of the grand-aumonier as far as service of the king's chapel was concerned. There was also 1 maître de ballet, 1 maître de danse (newly created), both officers. All other musicians and performers were appointed by commission, under the authority of the premiers gentilhommes de la Chambre.

surintendants:

The ceremonies organized by him were numerous: marriages, baptisms, oaths, lits de justice (when the king sat in Parliament), arrivals and departures of sovereing and princes, receptions of ambassadors and legates, Te Deum and public rejoicings, processions, coronations, etc. His symbol of authority was a staff topped by an ivory ball and covered in black velvet. The last holder of the position was the marquis de Dreux-Brézé, whose place in history was ensured by being on the receiving end of Mirabeau's oratory, when, on June 20, 1789, he told in vain the newly formed National Assembly to vacate the premises.

The reception of ambassadors by the king, queen and princes was handled by a specialized function, that of conducteur des ambassadeurs, initially subordinated to the grand-maître des cérémonies, but by the reign of Louis XIV the position, now called introducteur des ambassadeurs, had become independent of him. Sainctot held that position under Louis XIV. He was assisted by a secrétaire ordinaire pour la conduite des ambassadeurs. Both were under the grand-maître de France.

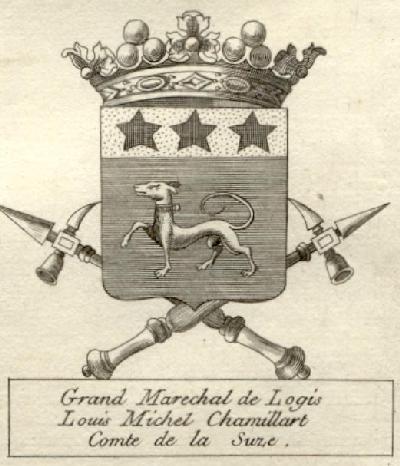

This department handled lodgings for the court and the king's household (civil and military) when travelling. Its head was the grand maréchal des logis, who reported directly to the king and gave his oath directly to him. Under him were 12 maréchaux des logis, serving by quarter. They assigned lodgings to the members of the king's travelling party and decided on the route taken by the troops of the king's household. They were also in charge of the king's quarters when campaigning in wartime. Under them 48 fourriers des logis (harbingers) went out to scout the location and report on the available lodgings to the maréchaux, who then decided the assignments. The fourriers then went back and marked in white chalk the name of the assignee on the door of each lodging. The name was preceded by the word "pour" (e.g., "pour le roi") for the highest-ranking individuals only, such as the king, the queen, royal princes, foreign princes, cardinals, and the chancellor.

The capitaine général des guides des camps et armées du Roi was a military officer who gave his oath to the dean of the maréchaux. He was nominally in charge of the itinerary of the king. The wagmestre des équipages du Roi and his aide wagmestre (offices created in 1667) directed the wagons of the king's retinue. They took their oath from the grand-maître de France.

The stables were divided into the grande écurie and the petite écurie. The former consisted of the riding horses for war and dressing, the latter of horses for drawing carriages. The petite écurie was under the premier écuyer commandant la petite écurie, who had some degree of independence from the grand écuyer. When the king died, the horses and equipment of the grande écurie went to the grand écuyer, while those of the petite écurie went to the premier écuyer.

There was within the grande écurie, under the grand écuyer, a premier écuyer de la grande écurie, a écuyer ordinaire, and 20 écuyers serving by quarter. The écuyer on duty was constantly near the king: he was present at the king's rising to learn if the king would ride, he put the spurs on the king's boots and rode immediately behind him along with the officer of the lifeguards, helping the king whenever necessary. Other officers were the écuyers cavalcadours, the 42 grands valets-de-pied, 4 maîtres palfreniers, 4 palfreniers, 4 cochers du corps du Roi, 1 cocher du Roi en postillon du corps, 4 maréchaux, and a number of chevaucheurs or couriers du Roi.

A number of musicians were part of the stables: 12 trompettes, 12 hautbois, 8 fifres & tambours.

At the very end of the Old Regime, a position of directeur général des haras, postes aux chevaux, relais et messageries (postmaster) was created to supervise both the state-owned horse-farms, the postal service, and the privately run messenger services. An intendant served under him.

The grand fauconnier (grand falconer) had under him several gentilhommes de la fauconnerie (whose numbers were reduced in 1748), a secrétaire, an aumônier, a maréchal des logis and 2 fouriers, and teams for each type of hunt (or vol): milan, heron, corneille (blackbird), rivière (duck and waterfowl), champs (partridge and pheasant), pie (magpie), lièvre (hare). Each vol has its capitaine, lieutenant, maître fauconnier, porteduc,piqueurs.

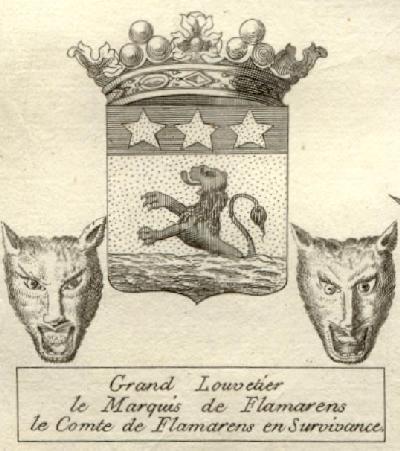

The grand louvetier (wolf-catcher) had under him 2 lieutenants, 1 sous-lieutenant, 4 valets de limiers, 2 valets de chiens courants, 1 garçon de levriers, 1 garçon de limiers, 1 garçon de chiens courants, 2 gardes-laisses des grands levriers, 1 conducteur des charois, etc.

The direction of this administration was entrusted to a surintendant, but the position was abolished in 1708, recreated in 1716 and finally abolished in 1726, replaced by a directeur et ordonnateur général des bâtiments, jardins, arts, académies et manufactures royales who held the office in commission. Under him were, until 1776, a premier architecte du Roi, several intendants et ordonnateurs généraux, and several contrôleurs généraux; after 1776, there were 3 intendants, 1 architecte ordinaire, 1 inspecteur général, and 4 contrôleurs.

Surintendant des bâtiments:

The cavalry consisted of the gardes du corps (dedans),

the gendarmes de la garde du Roi, the chevaux légers,

the mousquetaires, the grenadiers à cheval (dehors).

The infantry consisted of the cent suisses, the gardes de la

porte, the gardes de la prévôté de l'hôtel,

(dedans), the gardes françaises, and the gardes

suisses (dehors).

To be completed.