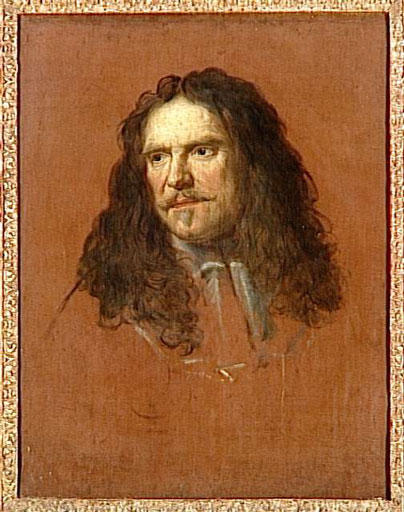

Portrait of Robert III de La Marck, maréchal de France (19th c. copy of a 16th c. original). (Source: Ministère de la Culture, base de données Joconde.)

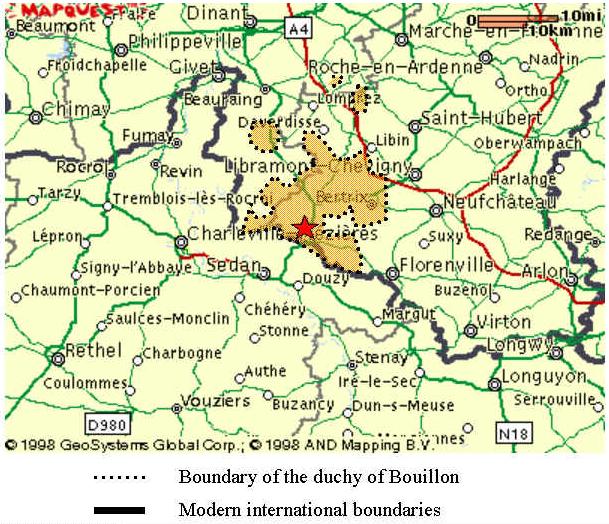

The small town of Bouillon is in Belgium, province of Luxembourg, close to the French border. Its population was 5,577 in 1994.

Built as a fortress in the early 11th c., it was ceded by the famous crusader Godefroy de Bouillon to the bishops of Liége, who owned it until 1678. From 1678 to 1795, it was an independent and sovereign territory under the La Tour family. Annexed by France in 1795, it seemed to be on the verge of reappearing in 1814 with an English admiral as duke, but the congress of Vienna gave it to the Netherlands.

This page tells the story of Bouillon.

It was part of Lotharingia and later (in 959) Lower Lorraine; in one reference it is called an allodial domain in the county of Ardenne. Sometime around 1020, Godefroid, duke of Lower Lotharingia, builds a castle on the site. It was destroyed by the emperor's troops when Godefroid's son Godefroid the Bearded rebelled in 1045. He returned to favor and was made duke of Lower Lotharingia in 1065, and rebuilt the castle. He was succeeded as duke by his son Godefroi the Hunchback. In 1082, Godefroi de Bouillon, son of Eustace de Boulogne and Uida of Ardenne, and nephew of Godefroi the Hunchback, inherited the duchy of Lower Lorraine. When the First Crusade was called, he decided to join it. To finance his participation, he sold Bouillon to Orbert, bishop of Liége, for 1300 marks of silver and 3 marks of gold (1 mark=230g), with the assent of his mother (Gilles d'Orval, vie d'Orbert). He went on to take part in the capture of Jerusalem (1099); he turned down the crown of the newly formed kingdom, preferring the title of Guardian of the Holy Sepulcher, and died in 1100. He left no direct heirs, and his two brothers died in 1118 and 1125 respectively. The contract gave to Godefroy and his next three successors the right to repurchase the duchy at the same price, failing which the duchy would remain in perpetual possession of the bishopric of Liége. The option was apparently not exercised, although a collateral heir, Renaud, count of Bar, seized Bouillon in 1129. The bishop of Liége retook Bouillon by force in 1141, and the emperor confirmed his rights to Bouillon in 1155.

It is not clear when the title of "duke of Bouillon" appears, but it was certainly later than Godefroy. One early instance is an act of 1291 by which the bishop names several of his vassals as peers of Bouillon: The bishop is styled "mon signour l'eveske de Liége, duch de Bouillon et de l'abbeit de Saint-Hubert". The bishops of Liége styled themselves "par la grâce de Dieu évêque de Liége, duc de Bouillon, comte de Looz, etc", starting with Jean de Hinsbergh in 1456, and every bishop did so until 1794 (see for example the first quarter in the arms shown on a gold ducat of 1763). In fact, the present-day arms and flag of the province of Liége include a quarter with the arms of Bouillon.

Most likely, ducal rank was attached to the territory because it had once been part of the duchy of Lower Lorraine; just as Brabant inherited the title of duchy. By the Modern era, it does not appear that Bouillon was considered a part of the Holy Roman Empire: it is not listed in standard 18th century references.

The arms of the duchy of Bouillon were: Gules a fess argent (identical to the arms of Austria).

Meanwhile, the La Marck family, which bought the sovereign lordship of Sedan in 1424, was taking root in France. Robert III (1492-1536) became maréchal de France in 1526, his son Robert IV (d. 1556) was also maréchal de France in 1547. They both styled themselves, and were called in France (e.g., in the letters patent of 1547 appointing him maréchal de France), duc de Bouillon. Robert IV had two sons: Henri-Robert (1529-74) and Charles-Robert (1539-1622), comte de Maulévrier. Henri-Robert married Françoise de Bourbon, daughter of Louis duc de Montpensier (and second cousin of the father of Henri IV). They had Guillaume-Robert (1562-88) who died unmarried, Jean (1564-87) who died unmarried, and Charlotte (1574-94).

In 1588, at the death of her brother, Charlotte became the heir to Sedan and to the claims on Bouillon. She married on October 15, 1591 Henri de La Tour, vicomte de Turenne, maréchal de France in 1592 (1555-1623) a protestant and one of Henri IV's lieutenants in his attempts to enforce the latter's claim on the throne of France. In the marriage contract, each party named the other one as heir. Charlotte's will dated April 8, 1594 and registered in the sovereign Court of Sedan contains the same disposition (France, Archives Nationales, 273 AP 176, dossier 7). When Charlotte died on 8 May 1594 without children, Henri became her heir, and thus prince of Sedan and titular duc de Bouillon Her paternal uncle, the comte de Maulévrier, and her maternal cousin Henri de Bourbon, duc de Montpensier, disputed the validity of the contract, because it violated the entail established by her father in his will. In the end, an agreement was concluded with the comte de Maulévrier on August 5, 1601 (cited by La Chesnaye-Desbois, s.v. Sedan) and with the duc de Montpensier on Oct 24, 1594, whereby the duc relinquished his claims in exchange for an annuity (Archives Nationales, 273 AP 179). The disputes apparently continued because there are letters patent of July 13, 1648 concerning the dispute over the sovereignty of the duchy between the comte de La Marck (Maulévrier), Frédéric-Maurice de La Tour and the duc d'Orléans as tutor of his daughter the duchesse de Montpensier (Archives Nationales, 272 AP 233).

Parenthetically, the line of Maulévrier continued to use the title of duc de Bouillon. Charles-Robert left a daughter without issue and Henri-Robert II (1575-1652), who left only a daughter Louise, married in 1633 to Maximilien Eschalart, seigneur de La Boulaye. Their son took the name and arms of La Marck to assert his claims to his maternal heritage. His only daughter married Jacques-Henri de Durfort, duc de Duras (1670-97), who left two daughters, Jeanne-Henriette (b. 1691) and Henriette-Julie. The former married Louis de Lorraine, prince de Lambesc (d. 1743) by whom she had Louis-Charles de Lorraine, comte de Brionne (1725-61). The latter married Procope Pignatelli, comte d'Egmont, duc de Bisaccia (d. 1743) by whom several children.

Henri

de La Tour was the head of the junior branch of the La Tour ![]() family.

The La Tour had become comtes d'Auvergne

family.

The La Tour had become comtes d'Auvergne![]() and Boulogne

and Boulogne![]() , by the marriage

of Bertrand IV de La Tour in 1389 to Marie d'Auvergne, daughter of Godefroy

of Boulogne, Lord of Montgascon; the eldest son Bertrand V became comte

d'Auvergne, his line ending in 1501; the younger son Godefroi inherited

Montgascon. Earlier, however, a younger son of Bertrand II had received

the seigneurie d'Oliergues. Agne de La Tour, seigneur d'Oliergues (d. 1489),

married Anne de Beaufort, heir to the vicomté de Turenne

, by the marriage

of Bertrand IV de La Tour in 1389 to Marie d'Auvergne, daughter of Godefroy

of Boulogne, Lord of Montgascon; the eldest son Bertrand V became comte

d'Auvergne, his line ending in 1501; the younger son Godefroi inherited

Montgascon. Earlier, however, a younger son of Bertrand II had received

the seigneurie d'Oliergues. Agne de La Tour, seigneur d'Oliergues (d. 1489),

married Anne de Beaufort, heir to the vicomté de Turenne![]() .

His two sons were Antoine and Antoine-Raymond, the latter's posterity continuing

to the 19th century. The former's son François (1497-1532) married

Anne de La Tour de Montgascon, heir of Godefroi cited above. Their grandson

was Henri de La Tour. After they inherited Bouillon

.

His two sons were Antoine and Antoine-Raymond, the latter's posterity continuing

to the 19th century. The former's son François (1497-1532) married

Anne de La Tour de Montgascon, heir of Godefroi cited above. Their grandson

was Henri de La Tour. After they inherited Bouillon ![]() in

1594, the arms of the family became: Quarterly La Tour, Auvergne, Turenne,

Bouillon, over all Boulogne (first appearance on a coin of 1614) and

later still: Quarterly 1 and 4 La Tour, 2 Boulogne, 3 Turenne, over

all Auvergne impaling Bouillon. A map of Clermont-Ferrand dated 1739

and visible at Gallica shows the arms

of the duc de Bouillon supported by two griffins sejeant regardant crowned

and an open ducal coronet.

in

1594, the arms of the family became: Quarterly La Tour, Auvergne, Turenne,

Bouillon, over all Boulogne (first appearance on a coin of 1614) and

later still: Quarterly 1 and 4 La Tour, 2 Boulogne, 3 Turenne, over

all Auvergne impaling Bouillon. A map of Clermont-Ferrand dated 1739

and visible at Gallica shows the arms

of the duc de Bouillon supported by two griffins sejeant regardant crowned

and an open ducal coronet.

Parenthetically, the senior line of La Tour ended with Jean, grandson of Bertrand V, who died in 1501. By Anne de Bourbon he had two daughters: Anne, married in 1505 to John Stuart duke of Albany and died without issue in 1524; and Madeleine, married to Lorenzo de Medici, duke of Urbino. The counties of Auvergne, Boulogne and the baronny of La Tour passed to the daughter of Madeleine, Catherine de Medici, wife of Henri II of France. On her death in 1589, the baronny of La Tour passed to Marguerite de Valois, daughter and only surviving child of Catherine. She gave La Tour to Louis XIII. However, there were other claimants: Jean de La Tour, last comte d'Auvergne, had a sister Louise, who married Claude de Blaisi; their daughter Suzanne married in 1508 Christophe de Rochechouart, seigneur de Chandonnier. Their great-grandson Jean-Louis de Rochechouart pursued the matter in court and won by an arrêt of Sept. 2, 1617 and settlements of January 2, 1620 signed by the king on Feb 2, registered in Parlement on March 18. Jean-Louis de Rochechouart received on October 1, 1621 possession of the baronny (but not the lordship, reserved by the king for himself) disputed since 1501. It was later sold in 1688 to Victor-Maurice de Broglie. The lordship of the baronny was given to the duc de Bouillon in the contract of 1651 discussed below.

Henri de La Tour now called himself duc de Bouillon, prince souverain de Sedan (see, for example, an écu coin struck in Sedan in 1613, bearing the legend "Henricus de La Tour dux Bullionaeus supremus princeps Sedanensis"). Letters Patent of March 1595 were registered in Paris on 9 May 1596, "confirmant au duc de Bouillon marechal de France, prince souverain de Sedan et Jametz, les privilèges, franchises, libertés et exemptions qui lui ont été accordées ainsi qu'à ses sujets par les précédents Rois".

Once widowed, Henri de La Tour married Elisabeth of Nassau, daughter of William the Silent, and the line of the La Tour ducs de Bouillon descend from this marriage. Their two sons were Frédéric-Maurice (1605-52) and Henri de La Tour, vicomte de Turenne, the famous maréchal de France (1611-75, without issue).

Frédéric-Maurice, raised as a Calvinist, was in the service of the Estates-General of the Low Countries, and hoping to succeed his maternal uncle. But he fell in love with Éléonore-Catherine de Bergh, a fervent Catholic whom he married against his family's wishes in 1634. Soon he converted to Catholicism (1636) and started getting involved in French politics, siding at times with Spain and the internal enemies of Louis XIII, and at times receiving military commissions in the French army. On September 3, 1641 he signed a convention with Liége, whereby he renounced a number of his claims, including the claim to the sum promised in the treaty of 1484, against payment of 150,000 guilder of Brabant which took place in 1658. The claim on Bouillon was a consequence of the treaty of 1484, so it was implicitly rendered moot after that payment; but the text of the convention of 1641 does not contain any explicit renunciation to the claims on Bouillon (see text in Polain). In 1641 he was implicated in the Cinq-Mars conspiracy against Louis XIII, arrested and was about to be tried for treason when his wife threatened to open Sedan to the Spanish army. Sedan was a strategic fortress on the Meuse river, opening the way to France from the Ardennes. Richelieu, the prime minister, relented and pardoned Bouillon, but after extracting from him a promise to cede Sedan and Raucourt to France (offer made on 13 Sep 1642, pardon made on 15 Sep, registered in Parlement on 5 Dec; see G. F. von Martens, Cours Diplomatique (1801), 1:220). After Louis XIII's death Bouillon was involved in the Fronde against Mazarin, who finally bought his adherence to the royal party with a sufficient compensation package for Sedan.

A first agreement, or traité, had been signed on March 1647, assenting to the principle of an exchange of the sovereign principality of Sedan and Raucourt, and of the portions of the duchy of Bouillon under the duc's control, located in the recette generale of Sedan. Commissioners were appointed to assess the value of the principality; their first estimate of June 15 and October 4, 1647 was rejected by the duke as too low. Another set of commissioners was appointed on Sept. 30, 1648 and their estimate of a revenue of 104,904 livres, proposed on June 1, 1649, was adopted by Arrêt du conseil of July 20. The procedure for the exchange was to capitalize the revenue of Sedan, Raucourt and the fragments of Bouillon at 100, to reflect the value of sovereignty; to capitalize the estates offered in exchange at 40 up to 70,000 livres of income, and any income above that sum at 25; and to equate the two capitals. Thus, the duc de Bouillon ceded 105,000 livres of annual income in exchange for 378,000 livres in annual income. For purposes of comparison, the daily wage for a laborer in the construction industry in Paris was about 0.7 livre per day, perhaps 150-200 livres per year. Per capita income for France as a whole was about 100 livres. One way to think of the 378,000 livres is that it represented 3780 times per capita income; for the US in 1998, that would be the equivalent of an annual income of $116 millions...

On the basis of the proposed estimation, a contract was signed on 20 March 1651, between the king of France "en foi et parole de Roy" and the duc de Bouillon, prince souverain de Sedan et Raucourt, "en foi et parole de prince." The prince received the duchies of Château-Thierry and Albret with rank of peer, the counties of Évreux, Auvergne, Beaumont-en-Périgord, the châtellenies of Poissy and Gambais. In exchange, the prince gave to the king Sedan and Raucourt, and all portions of the duchy of Bouillon currently in his possession "sans rien excepter ni reserver, sinon les droits qu'il a au chasteau de Bouillon, & les portions dudit duché usurpées sur les predecesseurs dudit seigneur duc de Bouillon & detenues par le roy d'Espagne & par l'évêque de Liege, qui demeurent reservées audit seigneur duc de Bouillon, pour en faire le recouvrement, ou en disposer a son profit, avec le gré & consentement de Sadite Majesté. Et au cas que par l'entremise de Sadite Majesté, ou autrement, ledit seigneur duc de Bouillon rentre en la possession dudit duché, le Roy y pourra mettre à l'instant & entretenir pour seureté dudit chasteau telle garnison que Sa Majesté aura agréable, sans qu'audit cas le seigneur duc de Bouillon puisse demander au Roy aucune recompense pour la non-jouissance de la portion de ladite terre possedée tant par le roy d'Espagne, que par l'évêque de Liege." (Dumont 6:2:3). An arrêt of the Parlement de Paris registered the contract and declared Bouillon to be sovereign and independent (21 Aug 1657; Dumont 6:2:189).

Royal brevets of April 2 1649, October 26 1649 and February 15, 1652 granted to the duc de Bouillon and his brother the maréchal de Turenne rank and precedence of foreign prince (the La Tour enjoyed rank of duke by brevets of June 2, 1607 and February 29, 1612, although the duchy was not in France). Initially, the new duc d'Albret and Chateau-Thierry was to take rank from an earlier creation of the latter duchy in 1526 for Robert III de La Marck but never registered. This, however, met with the opposition of the dukes-peers, and a revised document gave him rank as of February 20, 1652. He died before his reception as peer, and his son was not confirmed as peer until November 27, 1665.

The comte de La Marck, representative of the Maulévrier line,

lodged protests with the Parlements, but his protests were preempted (évoqués)

by the Conseil du Roi on May 20, 1651. Registration of the contract in

the relevant Parlements and the Chambres aux Comptes were made with some

restrictions, mainly placing restrictions on the duc de Bouillon's enjoyment

of certain rights attached to the lands he was receiving, and imposing

on him the obligation of reimbursing certain engagistes and officers in

the domains he was receiving. The king, wanting to have the exchange

concluded swiftly, issued lettres de jussion stating his intention

"que ledit contrat soit exécuté promptement, entièrement

et de bonne foi, comme étant un échange, un contrat du droit

des gens, un traité fait avec un prince souverain, une acquisition

de nouvelle souveraineté très avantageuse au bien de notre

Estat qui est au-dessus de toutes autres considérations; que nous

sommes obligés en foi et parole de Roy envers notre dit cousin le

duc de Bouillon de le faire jouir pleinement, paisiblement, ses hoirs,

successeurs et ayans causes, des terres données en contr'échange

[…]” .

The 2d duke Frédéric-Maurice (1605-52) left:

In 1672 war broke out between France and Spain. The bishop of Liége sided with the Spaniards, and in 1676 the maréchal de Créquy seized Bouillon. An arrêt du conseil of May 1, 1678 carried out the promise of the contract of 1651 and ceded Bouillon to Godefroy-Maurice, to be held etc. French troops were placed in the fortress of Bouillon, but a règlement of April 17, 1717 severely restricted the powers of the commander of the castle of Bouillon: for example, all matters of police in the city of Bouillon itself were left to the duke's officers, the commander had power of arrest only on his soldiers, the commander could not requisition anything himself, but rather had to ask the city for the necessary provisions, etc.

The treaty of Nimeguen of 1679 confirmed Godefroy-Maurice in the possession of Bouillon. The bishops of Liége protested, and renewed their demands for a return of the duchy to them at the peace negotiations of Ryswick and Utrecht (protest of the plenipotentiary of the bishop of Cologne to the congress of Ryswick, 30 Oct 1697; Dumont 7:2:433). A formal protest was also issued in 1757 during a visit of Bouillon by its duke. Until the bishops lost their temporal powers with the French invasion of 1794, they did not cease to assert their claims.

Essentially, the sovereign duchy of Bouillon was under French military protection, in the same way that the principality of Monaco was since the treaty of Peronne in 1641. Vauban called Bouillon "the key of the Ardennes", and the French king had a strong interest in depriving the Spaniards (after 1713, the Austrians) of that key.

In all other respects, Bouillon was a sovereign duchy, albeit a very small one. With an area of 55 square miles (modern-day Liechtenstein is 61 square miles) and a population of about 2,500 in 1789, the duchy of Bouillon included the town itself, lodged in a meander of the Semois river, with the medieval fortress on its ridge; and surrounding villages of the Ardennes (including Sugny, Corbion, Alle, Rochehaut, Ucimont, Botassart, Sensenruth, Noirefontaine, Gros-Fays, Fays-les-Veneurs, Bertrix, Carlsbourg, Paliseul, Jehonville, Beth-les-Abbies, Anloy, Porcheresse; and the enclaves of Gedinne and Sart to the west, Tellin, and Auffe to the north.) There were some disputes with Liége over some territories such as Muno and Bertrix. The duc de Bouillon claimed that the abbey of Saint-Hubert, Hierges, Mirwart were "peerages" of the duchy and subject to his jurisdiction, although in fact controlled by Liége.

The duchy's judicial system included lower courts, upper courts and a Cour Souveraine in Bouillon, where all important edicts and laws were registered. It was governed by its own laws and customs, reformed most recently by the bishop of Liége in 1628. In fact, the hundreds of years under Liegeois sovereignty had not resulted in any absorption of Bouillon. When, in 1646, the city of Liége tried to levy a contribution to military expenses on Bouillon, the Cour souveraine and the officers of the duchy protested that they were "indépendans et de tous temps n'ont eu rien de commun avec les États de Liége pour estre une souverenitéz particulière" (petition of 30 Aug 1646, in Bodard 1977); the bishop sided with them and rescinded the taxes. The duc had vassals (even peers), created nobles and granted titles. He collected taxes and maintained roads and infrastructure. The Bouillonais had their own nationality, and the duc naturalized foreigners on occasion. The duc had his own mint, opened by the bishops in 1611. Minting was one of the most jealously guarded regalian powers at the time, because it could be an important source of revenue, not so much with the gold and silver coinage (which was minted at the standard of France) as with the copper coinage, which circulated at higher value than its intrinsic content. The ducs de Bouillon minted quantities of small copper coins in close imitation of the French coins (with a tower among the fleurs-de-lis on the reverse) to take advantage of the fact. In that, they were following the practices of numerous other principalities (Dombes, Orange, etc). Since Bouillon was a sovereign country, it was in principle out of the reach of the French censors and the French police, which is why it became a haven for the "subversive" publications of the Encyclopédistes after 1760. An international incident took place once when French police entered Bouillon, and the duc protested to the French minister of Foreign Affairs, Choiseul.

As a sovereign principality in or near French territory, Bouillon was not unique (see the page on French principalities). Dombes, Henrichemont, Monaco, Orange, Chateau-Renaud, Arches-Charleville, Monaco were other examples. Several of these (Dombes, Orange) were, like Bouillon, remains of the kingdom of Lorraine which existed in the 9th century between France and Germany. The history of Dombes is particularly instructive, as it shows that, in the 17th and 18th cneturies, the notion that a sovereign principality could be donated or sold was accepted as a matter of course.

The 3d duke Godefroy-Maurice (1641-1721) left:

The terms of the entail came to play an important role after 1815, when several claimants disputed the duchy after the extinction of the male line of the groom.

The content of the donation was the sovereign duchy of Bouillon, the viscountcy of Turenne, the duchy of Albret, the county of Auvergne and baronny of La Tour, and the Paris residence of the Bouillon family. The entail was not perpetual but "for as many degrees as allowed by the law and customs of the region where each estate is located". It excluded all males who were members of religious orders. It was established in the following order:

Substitutions (entails) existed in France under Roman law (mainly the south), which emerged in the Middle Ages (see Augustin 1980 for an introduction; entails were commonly used in Spain and Italy). It allowed a donor or testator to subject the estate he was giving to certain conditions on their transmission. The law on entails was very complex, and varied from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Common law regions were generally hostile to it, while written law or Roman law regions (the south of France) were more receptive.

By the late Middle ages, Romanists (jurists specializing in Roman law) had invoked the Novella 159 (one of Justinian's Novellae) to limit entails to four degrees beyond the initial recipient or grantee. This principle was accepted by all jurisdictions that allowed entails, but there was some dispute as to what constituted a "degree": was there a new degree each time the estate was inherited, or did a degree require a change of generation? The latter interpretation allowed for longer-lived entails, and it is the one to which the parlement of Toulouse clung tenaciously. The French kings, on the other hand, tried several times to limit entails to two degrees, and to interpret degrees as individuals, not generations. The Ordonnances of Orléans (1560), Moulins (1566) and 1629 all restricted entails to two degrees interpreted as individuals, but some parlements (mainly Toulouse) resisted and refused to register the relevant clauses. Toulouse thus allowed for four degrees counted as generations, Bordeaux allowed for four degrees counted as individuals, and most other parlements received the royal law and allowed two degrees counted as individuals. It is noteworthy that several common laws outlawed or severely restricted entails, including the customs of Sedan and Auvergne (cited in Augustin 1980). I have been unable to determine if the custom of Bouillon allowed entails. The feudal laws printed in Polain (1868) make no reference to entails.

The edict of 1711 on duchies-peerages allowed holders of a peerage to establish a perpetual entail on the "chef-lieu" or capital of the duchy and estates up to an annual income of 15,000 livres, notwithstanding the ordonnances of Orléans and Moulins and any other laws or customs (article VI). Article X made the dispositions of the edict applicable to duchies which were not peerages. Of course, Bouillon was not a French duchy, and the substitution of 1696 was established before 1711 (nothing in the edict of 1711 makes it retroactive).

Finally, an edict of 1747 made the law on entails uniform across France, and henceforth limited them to two degrees counted as individuals. Existing entails were to be executed under the regime in force locally prior to 1747. Toulouse and all other parlements accepted the edict. The Napoleon Civil Code prohibited entails (article 896), a disposition which remains in force, with very limited exceptions allowing for one degree-entails.

The creator of a entail could place conditions on the transmission, typically restricting to the male line, or placing females after males, in a variety of fashion. As long as the instructions were clear the enforcement was not a problem, but ambiguities arose often. In case of extinction of males, the jurisprudence did not clearly opt in favor of the closest female kin, and often found in favor of the lines representing the donor's daughters.

The 4th duc de Bouillon was Emmanuel-Théodose (1668-1730). None of his siblings left issue. Emmanuel-Théodose married several times: in 1696 Marie-Armande-Victoire de La Trémoille (1677-1717), in 1718 Louise-Angelique Le Tellier (1699-1719), in 1720 Anne-Marie-Christine de Simiane (1698-1722), in 1725 Louise-Henriette-Francoise de Lorraine (1707-37). He had by them:

,

of whom Louis-Henri-Joseph (1756-1830) duc de Bourbon and Louise-Adélaïde

(1757-1824), who both died without issue;

,

of whom Louis-Henri-Joseph (1756-1830) duc de Bourbon and Louise-Adélaïde

(1757-1824), who both died without issue;

The 4th duke may have regretted his father's profligacy, but he was not much better. After his death in 1730, his estate comprised 2.8 millions in assets and 6 millions in liabilities. The viscountcy of Turenne was sold for 4.2 millions to the king of France to balance the books in 1738.

The only thing remarkable about the 5th duke Charles-Godefroy is that he was the only duke ever to visit Bouillon, in 1757. On that occasion the king of France issued an order (Apr 7, 1755) on the honors to be given by the French garrison in Bouillon to the sovereign duke. On that same occasion the bishop of Liége issued a protest (29 December 1757) reaffirming his claims to Bouillon (Ordonnances, p. 129). In his will of October 30, 1771, the 5th duke left Bouillon to his male posterity, with reversion to the king of France in case of extinction (Archives Nationales, 273 AP 206).

Charles-Godefroy, 5th duke, married in 1724 Marie-Charlotte Sobieska (1697-1740, widow of his older brother) and had two children:

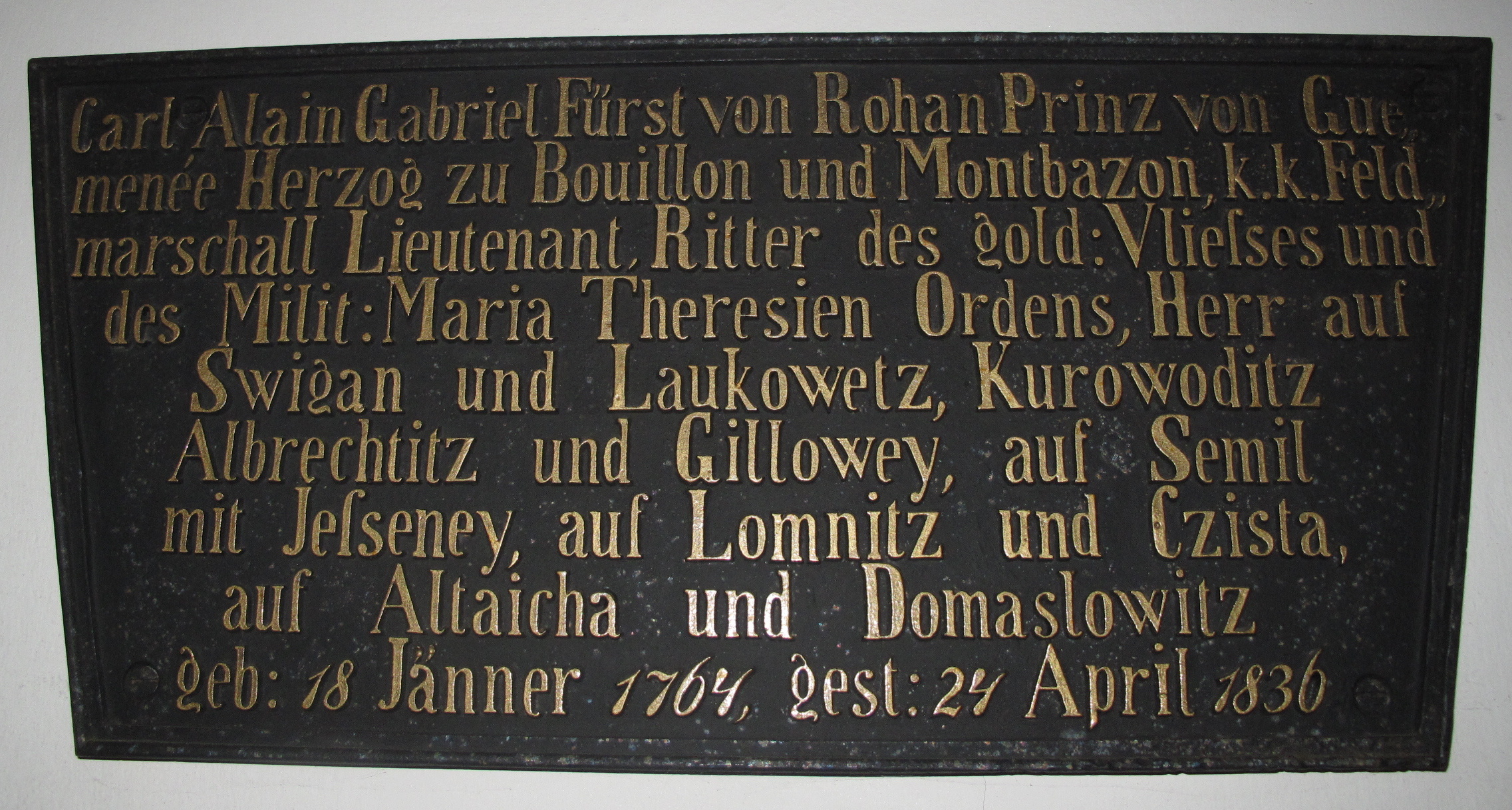

, prince de Guéméné,

duc de Montbazon, maréchal de France (1726-88). They had only one son,

Henri-Louis-Marie de Rohan prince de Guéméné (1745-1809),

who left three sons and one daughter by his cousin Victoire-Armande de

Rohan-Soubise. The eldest son was Charles-Alain-Gabriel (1764-1836), of whom a daughter

Berthe (1782-1841), followed by Louis Victor Meriadec (1766-1846), without issue

by his niece Berthe; and Jules Armand Louis (1768-1836) without issue. The daughter

Marie Louise (1765-1839) married her cousin Charles Louis Gaspard de Rohan-Rochefort,

from whom is descended the present head of the house of Rohan.

, prince de Guéméné,

duc de Montbazon, maréchal de France (1726-88). They had only one son,

Henri-Louis-Marie de Rohan prince de Guéméné (1745-1809),

who left three sons and one daughter by his cousin Victoire-Armande de

Rohan-Soubise. The eldest son was Charles-Alain-Gabriel (1764-1836), of whom a daughter

Berthe (1782-1841), followed by Louis Victor Meriadec (1766-1846), without issue

by his niece Berthe; and Jules Armand Louis (1768-1836) without issue. The daughter

Marie Louise (1765-1839) married her cousin Charles Louis Gaspard de Rohan-Rochefort,

from whom is descended the present head of the house of Rohan.

Godefroy-Charles-Henry married Louise-Henriette-Gabrielle de Lorraine (1718-88) and had two sons:

The 6th duke was an unusual character. As prince de Turenne, he served in the cavalry and reached the rank of maréchal de camp in 1748; he served again in the Seven Years War until 1759. He was a patron of the arts, and was elected to the Royal Academy of sculpture and painting in 1777; he was also a patron of artists, and was known to have spent 800,000 livres in three months on the Opera singer Marie-Josèphe Laguerre (the occasion for a song whose lyrics began: "Bouillon est preux et vaillant, il aime La Guerre..."). He created an order of chivalry for women, called La Félicité. In 1789, he married the fourteen-year old daughter of his mistress, over the objections of the bishop of Évreux. When the Revolution came, he embraced it: he submitted his own proposals (cahiers de doléances) to the Estates General, was elected commander of the national guard of Évreux on July 20, 1789, took part in the Fête de la Fédération on July 14, 1790, and was generally well-liked by his subjects in Bouillon and his tenants in Évreux. When the Bouillonais decided to form an Assemblée générale on the model of the French National Assembly and write a constitution for the duchy, he endorsed their project whole-heartedly, and ratified the Constitution they wrote in 1792.

The 6th duke was conscious of being near the end of his lineage, after the accident of 1767 left him with one physically unfit son. It is said that he commissioned archivists to research other possible branches of the family, particularly long-lost branches of the counts of Auvergne, from which he descended in female line. This research, begun in 1776, led to the discovery (or alleged discovery) of a younger son of Robert IV, comte d'Auvergne, who had moved to England in the early 13th century; his son Thiébaut had obtained in 1232 a grant land on the island of Jersey, and the lineage still existed in the late 18th century, with by Charles Dauvergne, esq., his brother major-general James Dauvergne (1726-99, s.p.), and his youngest son Philip Dauvergne, first lieutenant in the British Royal Navy, born in 1754 of his first marriage to Elisabeth Le Geyt. At the time, Philip Dauvergne, serving on the frigate the Arethusa, had been taken prisoner in March 1779, in the course of the Franco-British War of 1778-83 (also known as the War of American Independence), and was held in Brest. The French minister of the Navy, acquainted with the duke, informed him of the presence of the lieutenant on French soil, and had the lieutenant pay a visit to the duke at his castle of Navarre, on his way to Ostende where he was to embark for England. The duke and the English lieutenant got along well. (In another, more plausible version of the story, the genealogical researches were started only after this first meeting and miraculously found the connection between the families...). Philip Dauvergne was released and returned to duty, spending a miserable year on a failed attempt to colonize the islet of Trinidade (off the coast of Brazil). When he returned to London in 1784, promoted captain, he found the duke waiting for him. Dauvergne, free of his time, visited the duke in Navarre twice more, and finally the duke decided to adopt Philip Dauvergne. This was done by letters patent of May 4 and August 30, 1786. Philip's father gave his consent on September 1, 1786, and the adoption was registered in the College of Arms in London, by royal license, on January 1, 1787. Philip Dauvergne returned to service to command the frigate Narcissus, but resigned in 1790 because of ill-health due to his time on Trinidade.

On February 18, 1791, the General Assembly of Bouillon passed a decree asserting that the sovereignty of the duchy could not be mortgaged, alienated, exchanged or sold without express consent of the nation of Bouillon, and asking the duke to provide for the succession to his house in case (as everyone expected) his son died without heirs. The duke assented to all the clauses of the decree, except for one which required approval of the decree by the French National Assembly; at his request, the General Assembly of Bouillon removed that clause, and only asked that the duke petition for continued French protection.

Consequently, on June 25, 1791, the 6th duke issued a Declaration which called on Philip Dauvergne and his male issue to succeed his son if he died without male issue. The declaration was approved by his son on July 5, 1791. The declaration, the approval by the heir, the act of adoption, the approval by Charles Dauvergne, the registration by the College of Arms were all sent to the General assembly of Bouillon. On August 4, 1791, the General Assembly approved the decision, ordered that the declaration be registered by the Council of the duke in Paris and by the Cour Souveraine in Bouillon, sent to all lower courts, published in all townships and read in all parish churches; and it voided all prior dispositions, testaments, codicils, donations, cessions, sales, mortgages that could have been done by any prince of the reigning house. The dispositions were included in the Constitution of March 23, 1792, approved by the duke. Philip Dauvergne secured the royal license of George III to accept these honors on Feb 27, 1792.

In case of death of Philip Dauvergne without issue, an order of succession was fixed by the 6th duke, in a codicil to his will dated May 4, 1791. the codicil, locked in a box, was sent along with the other documents to the General Assembly, which deposited the box in the archives of the duchy and agreed to abide to the terms contained as long as they did not contradict any other decree (mention of the codicil is also made in the Constitution). The box was opened after the death of the 6th duke. According to Burke's Vicissitudes of Families, it contained the following order: Jacques Léopold and his male heirs; Philip Dauvergne and his male heirs; the heirs male of the Nicolas-François comte de La Tour d'Auvergne d'Apchier (b. 1710), a very distant relative and the only other line of La Tour still extant; the heirs male of Jean-Bretagne-Charles-Godefroi de La Trémoille; the heirs male of the house of Rohan-Rohan (G. R. Balleine, p. 55, gives the same order, without source).

When the 6th duke died on December 3, 1792 at Navarre, his son immediately proclaimed his adherence to the Constitution, by declaration of December 12. Later, when he was imprisoned during the Terror, the General Assembly of Bouillon decided that the institutions could not function any more since it was impossible to communicate with the chief executive. It called an Extraordinary General Assembly on Feb 7, 1794; the new assembly organized government by a decree of April 24, 1794 which did not explicitly abolish the "ducauté", but stated that the government was "essentially popular and democratic", and entrusted the executive to a committee. From then on, official documents ceased to make mention of the duke. The duchy was finally annexed by France on 4 brumaire IV (October 25, 1795), although the Assembly never assented and, rather daringly, publicly expressed its lack of consent.

Meanwhile, the Revolution in France was bringing trouble to the family of La Tour. The Assemblée Constituante saw as its mission the complete overhaul of French institutions and laws, reforming centuries of mistakes and abuses. Nothing in the past was safe from re-examination. One of the many areas ripe for reform was the management of the crown's domain, now called the national domain. Kings had imposed on themselves the discipline that the domain could not be alienated; but budgetary needs had often led them to enter in indefinite or perpetual leases, the engagements. Kings had also used portions of the domain for exchanges of territories, which was deemed allowable under the theory that an exchange did not diminish the total domain, merely replacing some estates by others of no lesser value. Whether the king was receiving anything real in exchange, or in fair proportion rather than as a favor, was often doubtful. The Guéméné exchanges of 1786 were a case in point, denounced as typical of Old Regime cronyism and corruption.

A complete reform of the management of the domain was proposed to the Assembly by its committee on the domain in November 1790, and a law passed (December 1, 1790). The section dealing with exchanges prescribed that exchanges which had not been completed, that is, for which the required procedures had not been entirely followed and final ratification obtained from the courts, were to be examined individually and decided upon by decree of the legislature (articles 18 and 19). The committee's report mentioned the fact that research into incomplete exchanges had already been carried out under the Old Regime, and a 800-page manuscript listing 102 questionable exchanges from 1647 to 1786 had already been compiled. The first date in all likelihood corresponds to the 1647 agreement over Sedan, the last to the Guéméné bail-out (Archives Parlementaires, 20:316-22, 653-6).

This new law probably worried the duc de Bouillon. Although the contract of exchange of 1651 had been preceded by two estimates of the value of Sedan and Raucourt (one in 1647, rejected as too low by Bouillon, and one in 1648), the contract had been only the beginning of a long process. Letters patent of March 1651 had been sent to the Parlements and the Chambres des Comptes for endorsement of the contraact and the appointment of commissioners to carry out detailed assessments of the estates; but the courts raised objections and amended the the terms of the contract. Louis XIV ordered his commissioners to proceed without the endorsement of the contract. After twenty years of work, the commissioners returned their assessments in 1674, but Bouillon objected that the commissioners had neglected certain expenses which should have been incurred by the king. New commissioners were appointed in 1676 to revise the assessments. A hundred years later, no progress had been made, and at Bouillon's request Louis XV appointed a new commission to examine the duc's complaints in 1770. By the time of the Revolution, the issues were still unresolved, and formally, the exchange had not been completed. In fact, an arrêt of April 2, 1776 from the Chambre des Comptes prohibited the duc de Bouillon from being done homage by the vassals of the domains he had received in the exchange, as long as letters of ratification had not been registered by the courts (Details are found in several petitions by La Tour d'Auvergne in AN AF/IV/32, as well as in the report on the law of 8 floréal II, see infra).

The Constituent Assembly had only opened uncompleted exchanges to examination. The committee had shied away from outright cancellation: "a general repeal would have created great disturbances in society, giving rise suddenly to a multitude of claims and suits capable of overturning the most secure estates." Its report, indeed, demonstrates how much thinking went into the bill, drawing on history and public law textbooks.

As the Revolution unfolded, attitudes changed. Soon after Léopold succeeded his father as sovereign duc de Bouillon in 1792, he took an oath to the constitution of Bouillon, and continued to reside at Navarre, near Évreux. A foreign war had begun, civil war had erupted, and fiscal revenues collapsed even as spending was exploding. The Convention was looking for any way to increase its resources, and Cambon, head of the finance committee, proposed to drastically revise the law of December 1790. It had not worked, he contended, and 18,000 lawsuits were clogging the courts. The Convention agreed, and the law of 10 frimaire II (December 10, 1793) that incomplete exchanges were immediately cancelled, all estates were to be taken over at once and the original counterparts of the exchanges returned (Archives Parlementaires, 1e Série, 79:104-10).

Léopold thus lost the vast majority of the estates which provided his income. He petitioned the Convention, arguing that these laws were not applicable to the contract of 1651 which, being a treaty between sovereigns, was only subject to international law and could not be revoked unilaterally. The committees of the Convention rejected his claim and upheld the cancelation in pure Jacobine language. Sovereignty belongs to the people, Bouillon's sovereignty was usurped and no claim could be based on it: "let him stop exaggerating the importance of the cession made by his ancestor to the tyrant of the French; it was void from the beginning in regard to the things he values so much; it was itself a political crime, because the policy of free nations knows no laws but those of nature." Obviously, sovereignty over Sedan could not be returned to Léopold, nor could. He could not claim the fortifications or any indemnity for them, since, "built for the people, their expense had been paid for with the people's sweat." nor could he claim any real estate that was of public use. "La Tour d'Auvergne, having become a French citizen, must have the character of one; and when everyone is rushing to make voluntary sacrifices, he will see without complaint the sacrifice which the laws of nature and reason demand from him." A law of 8 floréal II (April 27, 1794) rescinded the exchange of 1651 (Archives Parlementaires, 1e Série, 89:421-3).

The citoyen La Tour d'Auvergne was now deprived of most of his estates. The duchy of Bouillon was conquered in 1794 and annexed by France on October 25, 1795. One can imagine that the ci-devant duc's creditors were not getting paid much anymore. But the Terror came to an end, a less hostile regime replaced it, and La Tour d'Auvergne managed to get a law passed on 7 nivôse V (December 27, 1796) restoring all his estates to him. But after the coups of 18 fructidor V and 22 prairial VI, an arrêté is passed which sequesters all the estates of Bouillon related to the 1651 exchange (9 fructidor VI, August 26, 1798).

Then, a new law of 14 ventôse VII (March 4, 1799) offers a modicum of hope to La Tour d'Auvergne. It allows parties to incomplete exchanges to secure permanent ownership of the disputed estates on condition that they pay in cash 25% of the assessed value. La Tour d'Auvergne somehow finds the werewithal to make a submission for his estates, and to buy back in this manner his estates in Auvergne.

For him as for many others, Bonaparte's accession to power in November 1799 offered hope of a final resolution to the chain of events of the Revolution. He quickly obtained a decree of 1 germinal VIII (March 22, 1800) which ended the sequester of his estates and allowed him to regain possession. However, he was still obliged to pay the 25% of assessed value he had offered to pay, and woods larger than 150 hectares were returned to him only on a provisional basis. He continued to lobby for a permanent repeal of the law of 8 floréal II and a validation of the exchange of 1651, sending petitions to Bonaparte.

Meanwhile, he had to pay the bills, and his situation was grim. The loss of his income during five years had left him with 3 millions in debts, he was hounded by the tax collectors and his creditors, and his expenses exceeded current revenues by 200,000 F every year. In January 1801, he agreed to lease all of his estates to a syndicate of farmers who offered to pay his creditors themselves, pay his taxes, and leave him 100,000 F per year.

The citoyen Léopold La Tour d'Auvergne died in February 1802, the last of his name. Some of his relatives and heirs being émigrés (in particular his first cousin the prince de Guéméné, he of the bankruptcy), and because of the remaining uncertainty over the status of the 1651 exchange, his estates were once again placed under sequester on December 20, 1802.

When the forests in the Bouillon succession were united to the national

domain on 15 floréal XII (May 5, 1804), payment of the creditors

was allowed out of the revenues of these forests and by the Caisse de l'Administration

de l'Enregistrement et des Domaines, as a favor to the creditors, until

final resolution. Debates on what to do with the sequestered estates continued

within the French administration from 1807 to 1809. Heirs had presented

themselves, all of them collateral, and some quite distant (for the paternal

line, la dame de Rohan-Rochefort, la demoiselle de Rohan-Montbazon, daughter

and grand-daughter of the émigré Rohan-Guéméné;

for the maternal line, Colbert-Seignelay, Fernan-Nunez, Madame Veuve Montmorency,

and Bourbon-Busset).

It was found that the assets amounted to 5.93 million francs and the liabilities to 8.46 million francs, before even counting the State's claims under the cancellation of the exchange of 1651, valued at 10 million francs. Thus the heirs and the hundreds of creditors could expect little from more years of legal quagmire. The Conseil d'État advised that it would be worthy of His Majesty's generosity to confiscate all sequestered estates and add the creditors' claims to the public debt. The heirs would actually profit from the arrangement, since the chattel and a few estates had not been sequestered, and would be free from liens. The State would make a net loss, but it gained some handsome properties, including the hôtel de Bouillon on quai Malaquais, in Paris, and the castle at Navarre; and there is reason to suspect that the castle was wilfully underestimated by the State. This opinion was endorsed by Napoleon and approved by a decree of January 3, 1809. The domains were added to the domaine extraordinaire, and partly served to endow Napoleon's family. The castle and estate of Navarre was created as a duchy for Joséphine after the divorce, in April 1810 (it passed after her death to her son Eugène de Beauharnais; the castle was destroyed in the the 1840s; the estate returned to the State in 1853). The Paris hôtel was given to her cousin, Stéphanie, duchess of Bade (it is now part of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts).

On 27 April 1825, a law was passed (le Milliard des Émigrés) by which the State provided compensation to the victims of expropriations and confiscations during the Revolutionary period under laws against émigrés or counter-revolutionaries. The heirs to the Bouillon estate (Grammont, Bourbon-Busset and Seignelay) tried to obtain compensation under that law for the confiscation of 1809, but a decision of the Conseil d'État of Aug 1, 1834 rejected their claim.

Meanwhile, Philip Dauvergne was serving again in the British Royal Navy. He was stationed at Jersey in 1793 and given command of the defense of the islands, with the mission of helping the insurgency in Brittany and Normandy, running spies, infiltrating counterfeit currency to ruin the French economy. When the last duke died in 1802, the peace of Amiens soon followed, and Dauvergne went to Paris in August to try and assert his claims. But his activities in Jersey were known to the police, and he was thrown in jail, creating a diplomatic incident. The ambassador secured his release after seven days and he was expelled. War broke out again in May 1803, and he resumed his activities in Jersey, particularly heading a network of spies in France. He became Rear-Admiral of the Blue in November 1805, Vice-Admiral of the White in November 1813. In April 1814, after the defeat of Napoleon and his abdication, the Treaty of Paris returned France to its borders of January 1792, with some exceptions. By this treaty, almost all the former territory of the duchy of Bouillon was removed from France (the canton of Gedinne, to the west of Bouillon, remained French territory). Would the former duchy be reformed, and under whose sovereignty?

The retreating British troups left Admiral Dauvergne in command of Bouillon. There, he was recognized by the citizenry as the legitimate duc, in accordance with the law of the duchy before it was overtaken by the French revolutionaries and annexed. He adopted the prince of La Trémoïlle-Tarente, a general-major in the army of Baden, as his heir presumptive; La Trémoïlle obtained on January 22, 1815 the oath of loyalty of the inhabitants on behalf of the admiral. With the support of the officials of Bouillon, he sent a representative to the Congress of Vienna where the new map of Europe was being drawn.

But, at the Congress, another competitor presented himself: Charles-Alain-Gabriel de Rohan-Guéméné (1764-1836), eldest son of the only first cousin to the last duke, an Austrian citizen since 1808, general-major in the Austrian army (and entitled to the style of Durchlaucht). The prince de Rohan was undoubtedly the closest relative of the last duke on the paternal side. He argued of his right based on this relationship, and on the terms of a perpetual entail instituted by the 3d duke in 1696. The 6th duke himself had received the duchy by the terms of that entail, and therefore could not alter it but was subject to it. He also argued that the admiral's claims were based on "the anti-social principles of the French revolution" (see his Mémoire in Klüber: Acten des Wiener Congresses, vol. 4, pp.62-78).

It was agreed on February 12, 1815 that the duchy of Bouillon would be returned to the claimant whose rights had been established. On March 6, a commission was formed to examine the claims, with representatives of France, Austria, Prussia and the Netherlands. The Dutch plenipotentiaries expressed the opinion that the king of the Netherlands could not present himself as heir of the bishops of Liége, and thus would lay no claim to the duchy. They expressed the opinion, however, that it would be difficult to determine the rightful claimant, and that a special commission would be needed. The French and Dutch commissioners also expressed the view that it was dangerous to recreate such a small state in a boundary situation. Nevertheless, in article 4 of the treaty of May 31, 1815 between the Netherlands, Austria, Russia, Great Britain and Prussia, which defined the boundaries of the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, was the clause: "Des contestations s'étant élevées sur la propriété du duché de Bouillon, S.M. le Roi des Pays-Bas, Grand-Duc de Luxembourg, s'engage de restituer la partie dudit duché qui est comprise dans la démarcation ci-dessus indiquée, à celle des parties dont les droits seront légitimement constatés".

However, the commission presented a report on June 7, which was endorsed after deliberation, and the final act of June 9, 1815 proceeded differently. The sovereignty of the former duchy was attributed to the king of Netherlands as grand duke of Luxemburg, and Bouillon was united to the grand duchy. The property of the duchy (i.e., real estate belonging personally to the duke), as it was owned by the last duke, was to be owned by the claimant whose rights would be established, under the sovereignty of the grand duke of Luxemburg. An arbitral commission was established, composed of three members appointed by Austria, Sardinia and Prussia, and two members appointed by each claimant, Dauvergne and Rohan. In the meantime, the grand duke was to hold the said property in trust and turn it over to the victorious claimant. He was also to indemnify the claimant for the loss of sovereignty (the revenues from taxes and fees which the sovereign duke collected, but which the new owner of the property of the duchy would not). Finally, should the victorious claimant be Rohan, the estates would be subjected to the terms of the entail under which he claimed them. The grand duke of Luxemburg took possession of the duchy on July 22, 1815. After Napoleon's return and defeat at Waterloo, the Treaty of Paris was revised, and the new treaty in November 1815 included all of the former territory of Bouillon in the grand duchy (see the proceedings of the commission in Klüber, op. cit., vol. 9, pp. 208-230).

The arbitral commission finally met in June 1816 in Aachen. The vote was 4 to 1 in favor of Rohan, Dauvergne's commissioner Sir John Sewell (the only jurist on the panel) voting against. It is to be noted, however, that the Prussian delegate proposed that a légitime of 6 years' worth of the duchy's income be paid by Rohan to Dauvergne. A légitime, in French law, is that part of an estate which is reserved for the rightful claimant independently of the testamentary dispositions of the deceased. It is therefore apparent that the Prussian delegate recognized some legitimacy to Dauvergne's claim. The proposal was rejected by 3 to 2. The decision was handed down on July 1, 1816.

On September 18, Philip Dauvergne, ruined by the cost of the litigation, committed suicide at Holmes' Hotel, London; he was buried in St. Margaret's Church, Westminster. It is said that he made an "unfortunate marriage in India with a French woman named Damfrecourt, by whom he had a son", though I can't see when in his career he was ever in India. He also had three illegitimate children by Mary Hepburn of St. Helier, Jersey, to whom he gave his name: Anne Elizabeth (b. 1800), married to admiral John Aplin; Mary Ann Charlotte (b. 1794) married in 1815 to Sir Henry Prescott, later admiral; and Philip, who died a midshipman in Colombo in 1815 (presumably without issue.)

He also left a half-brother Corbet James Dauvergne (d. 1825), who married in 1823 a woman named Marie Victoire de Rohan. She was the illegitimate daughter of Ferdinand de Rohan, archbishop of Cambrai and great-uncle of Charles-Alain-Gabriel de Rohan, and of Charlotte Stuart, herself the illegitimate daughter of Charles Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie). No issue came of this curious marriage (see more details).

The property of the duchy was turned over to Rohan on September 17 and October 14, 1816. The resolution of the indemnity due to Rohan, which was left to be negotiated by the Congress of Vienna, took much longer, because of strong disagreements. Finally, on October 24, 1821, an indemnity was created by Arrêté royal. In the amount of 200,000 fl (about 400,000F), it took the form of a perpetual annuity at 2.5% in the name of Rohan. The interest accrued during the period since Bouillon was taken over by the grand duke was paid as a lump sum. A clause specified that the annuity and the property turned over in 1816, together formed a perpetual entail "in the order of succession existing in the former duchy of Bouillon"; but the arrêté did not say what that order was. Rohan accepted the terms on Dec. 8, 1821.

Rohan was not to enjoy freely the estate and the annuity. Other competitors presented themselves. The first challenge came in November 1816, when Godefroy-Maurice-Marie-Joseph de La Tour d'Auvergne d'Apchier (1770-1844), son of Nicolas-François-Julie who was named in the 6th duke's codicil of 1791, presented a memorandum to the diet of the German Confederation (of which Luxemburg was a member) asking to be given the possession of the duchy, but the Diet ruled itself incompetent. Despite this failure, he continued to press his claims in France. In 1821, he sued members of the La Tour d'Auvergne-Lauragais family (whose connection was, in fact, more than doubtful) to forbid them to use that name; they demanded in return that he be forbidden from using the title of prince and duc de Bouillon. On July 2, 1823 the court of the Seine departement ruled that they had no more claim than he did to the title, since it became extinct in 1802 and would remain extinct until such time as the king decided to grant it again; they thus had no legal standing. On appeal, the Paris court ruled in January 1824 that neither party had the right to use the name "Auvergne". On 3 Apr 1826, the Court of Cassation annulled the latter ruling as having been made ultra vires (Recueil Sirey 1826, 1.310; also Arrêts de la Cour de Cassation, partie civile, 1826, p. 132-145.) His only son Maurice-César died without issue in 1896, thus ending the line of La Tour d'Auvergne d'Apchier. In the 1890s editions of the Almanach de Gotha, Maurice-César is titled duc de Bouillon (but the Gotha, in all fairness, gave the same title at the same time to the prince de Rohan!).

Then, in 1817, several heirs presented themselves and sued in the court of Saint-Hubert (then part of the Netherlands, and seat of the district where Bouillon was situated). They were Charles-Bretagne-Marie-Joseph, duc de La Trémoïlle (1764-1839), Louis-Henri-Joseph, duc de Bourbon (1756-1830) and Louise-Adélaïde de Bourbon-Condé (1757-1824), and Anne-Marguerite-Louise de Beauvau, princesse de Poix (b. 1750). They were the representatives of the sisters of the 5th duke, while Rohan was the representative of the sibling of the 6th duke (neither the 4th duke's or the 7th duke's siblings had any issue).

Initially, the king of the Netherlands was reluctant to let the case proceed, as it might be seen as an attempt by his courts to reopen the act of the Congress of Vienna. Consequently, he issued an arrêté on May 4, 1817 sending the claimants to the signatories of the final act and declaring his courts incompetent. The prince de Rohan did not even bother to appear, and the court of Saint-Hubert declared itself incompetent by a judgment of March 28, 1818. The claimants appealed to the Appeals Court of Liege.

But, at the Congress of Aachen where the four Allied Powers were assembled, it was decided that, since the question of sovereignty had been settled, the dispute bore only on private matters which were within the purview of the local courts. This was entered in the minutes of the congress, and a written communication was sent to the king., who, on the basis of this decision by the signatories of the Congress of Vienna, revoked his earlier arrêté on June 19, 1819 and let the case proceed. The prince de Rohan filed a motion with the Appeals Court of Liége, arguing that the court was not competent to rule because the matter was essentially the determination of the rightful claimant to a sovereignty, a matter which was well above the competence of judicial courts. In an amazing twist of bad faith, the same prince who had dismissed the admiral's recognition by the people of Bouillon as "anti-social" and argued of his rights on the basis of a contract in private law, now argued that the rights to a sovereignty was well-above private law and could only be decided by the Bouillonais nation or the congress of Vienna which took over that power from the Bouillonais!

By a judgment of July 24, 1824, the Appeals Court of Liége awarded both the property of the duchy and the indemnity to the duc de Bourbon and his co-claimants. The estates and the indemnity were given without condition, "divisés entre eux, de libre disposition dans leur chef". The court first argued that it was indeed competent to rule, because only the matter of sovereignty had been arbitrarily decided by the Congress of Vienna, whose intentions to leave the matter of property to a fair judicial process were clear. Matters of property, by a universal principle, were in the cognizance of the courts in whose territorial jurisdiction the property was situated. The arbitration panel had only decided which of the two claimants had a better claim, but their judgment could not bind the other claimants. The Congress of Vienna had never proclaimed any obligation on the part of anyone to present its claims to it, and those who hadn't done so had not forfeited their rights. Then the court decided on the case itself against the prince de Rohan.

Unfortunately, the printed source omits the second part of the judgment. But the decision is not surprising, given the exact terms of the entail of 1696. Assuming that the entail was still applicable in 1802 (which, incidentally, was the fourth succession since the initial recipient), then, turning to the order of the entail:

Rohan appealed the decision to the Court of Cassation of Liége, on the grounds that the Appeals Court had acted ultra vires and violated the arrêté of 1821, by depriving him of the indemnity, and by freeing the indemnity from the entail indicated therein. The Court of Cassation, which is the highest court, handed down on November 16, 1825 a ruling upholding the appellate decision. In this ruling, the Court of Cassation upheld the reasoning of the Appeals Court, and also stated that the arrêté of 1821 did not represent a sovereign decision attributing property to Rohan, and therefore the decision of 1824 was not ultra vires. The prince de Rohan formally protested and "reserved his rights."

With the Revolution of 1830, the territory of the former duchy of Bouillon, along with most of the grand duchy, rebelled and joined with Belgium. The fortress of Bouillon was besieged on that occasion, for the last time in its history. Bouillon is now a part of Belgium.

Under construction.

A start (*) marks the books I have not consulted myself.