- See also an extraordinary collection of papal arms by Roberto Piperno, taken from various monuments in Rome

- Arnaud Bunel has produced a complete illustrated armory of the Popes.

Arms of the Papacy

A number of distinctions need to be made:

- the Pope, as an individual invested with a certain function.

- The Papacy, or the Holy See, that is, the institution which stands at the head of the Catholic Church.

- The Church, as a body.

- The Papal States, as a political entity, now consisting of the City State of the Vatican.

As an individual, the Pope usually has his own arms, either family arms or arms assumed at some point in his career. Since the Church uses heraldry abundantly, it is certain that anyone reaching the rank of bishop has arms already. Popes have had arms since the 14th c. at least. Boniface VIII (1294-1303) is the first pope for which we have contemporary evidence of his bearing arms; most 13th century popes had arms, but as they did not use tiaras or keys, it is difficult to attribute shields to them. Until 2005, a pope's arms were surmounted by the keys of St. Peter in saltire and above them a tiara with three crowns. This form dates back the the mid-14th century. See for example Benedetto Buglioni (1461-1521) : Wreath, with coat of arms of Pope Innocent VIII (1484-92) (48K) from the Musei Vaticani exhibit of the Christus Rex et Redemptor Mundi site. Notice the conical shape of the tiara, which is typical of medieval papal arms.

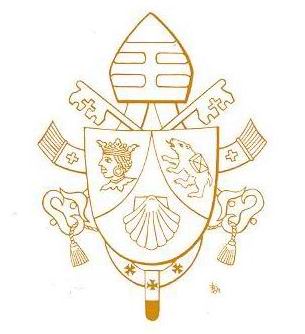

Elected in 2005, Benedict XVI has made important changes to the

external ornaments of the pope's arms. The tiara has been

replaced with a mitre decorated with three horizontal stripes and one

vertical stripe. Moreover, the arms are now surrounded by the

pallium, a white band of woollen cloth decorated with crosses patty

gules, which is the distinguishing marks of archbishops.

Arms of Benedict XVI

The arms are a little awkward to blazon in

English. In French, I would say "de gueules à la coquille d'or,

chapé ployé d'or, chargé à dextre d'une tête

de Maure au naturel couronnée et colletée de gueules, et à

senestre d'un ours au naturel lampassé de gueules et portant un fardeau de gueules

lié de sable".

Here is a picture of the arms seen from space (in the Vatican gardens).

The elements already appeared in his arms as archbishop of

that see (1977-82) and then as cardinal in Rome (except the escallop

was counterchanged on a field per fess wavy). The crowned Moor's

head is known in the arms of the bishops of Freising since 1316, and

was used after the secularization of Freising in 1803 by the

archbishops of Munich.

The backpacking bear, the so-called bear of Corbinian, recalls a legend

associated with this bishop who preached in Bavaria in the 8th c.

On a trip to Rome, the saint stopped somewhere in Tirol, and while no

one was guarding the animals a bear killed his mule; so the bishop told

one of his servants to take a whip, scold the bear and put the mule's

burden on the bear's back, which he did. Once arrived in Rome,

the bishop let the bear go free. In the legend, the bear

symbolizes the domestication of the heathens by Christianity.

The escallop is associated with the medieval pilgrims who walked to the

tomb of the Apostle James in Spain, and also appears in the arms of the

Schottenkloster (convent of the Scots) in Regensburg which is now the

diocesan seminary; Joseph Ratzinger taught in Regensburg from 1969 to

1977.

In an autobiographical work published in 1977, the present pope

explained the meaning of these charges for him. The Moor's head

represents the universality of the Church, accepting all without

distinction of race or class. The escallop denotes the pilgrim,

but also recalls a story about St. Augustine pondering the mystery of

the Trinity as he walked along a beach, and coming upon a child who was

playing with a shell and trying to fill a hole with the ocean's

water. And when he told the child that what he was doing

was pointless, the child told him: no more than you trying to

understand the Trinity. The pope has a particular attachment to

St. Augustine, on whom he wrote his dissertation in 1953. The

earlier version of the arms appealed more explicitly to the Augustinian

seaside encounter. As for the bear, the pope identifies with the

Bavarian animal who became a beast of burden against himself, and still

labors in Rome under the burden, not knowing when he will be free to go

home.

Here is the story of the bear, from the Acta Sanctorum (s.v. 8 Sep, Corbinianus):

In ipso autem itinere Romano pergendo, cum in Breones pervenit, juxta silvam quandam in castris manebat. Sed dum custodes equorum incaute obdormierunt, ita ut nullus vigilaret, ursus e silva egrediens sagmarium m Viri Dei excerpens comedit. Mane autem facto, dum expergiscebant custodes, invenerunt eundem ursum super ipsum sagmarium jacentem, & comedentem illum. Quod dum Ansericus prædictus Viri Dei minister agnovit, beato Corbiniano dixit. Hoc autem Vir Dei patienter serens, dixit eidem Anserico: Tolle flagellum istum, & vade ad eum, & viriliter illum verbera, & castiga pro delicto suo, quo nobis nocuit. Quod dum ille agere formidavit, dixit ei Vir Dei: Vade & noli timere, sed ut dixi tibi fac, ac postea mitte super eum sellam sagmarionam, & sterne illum, & illam sagmam super illum impone, & mina cum aliis cavallis in viam nostram. Ipse vero Ansericus fecit, sicut præceperat ei Vir Dei, & appositam super se sagmam ipse ursus quasi domesticus equus eandem sagmam usque ad Romam perduxit, ibique a Viro Dei dimissus abiit viam suam.

Arms of previous popes

Here are some coats of arms of popes from contemporary monuments:

Arms of Paul II (1464-71), Viterbo.

Arms of Gregory XIII (1572-85), he of the calendar: pavement of St. Peter.

Arms of Urban VIII (1623-44), S. Peter.

Arms of Innocent X (1644-55) on the Porta Portese.

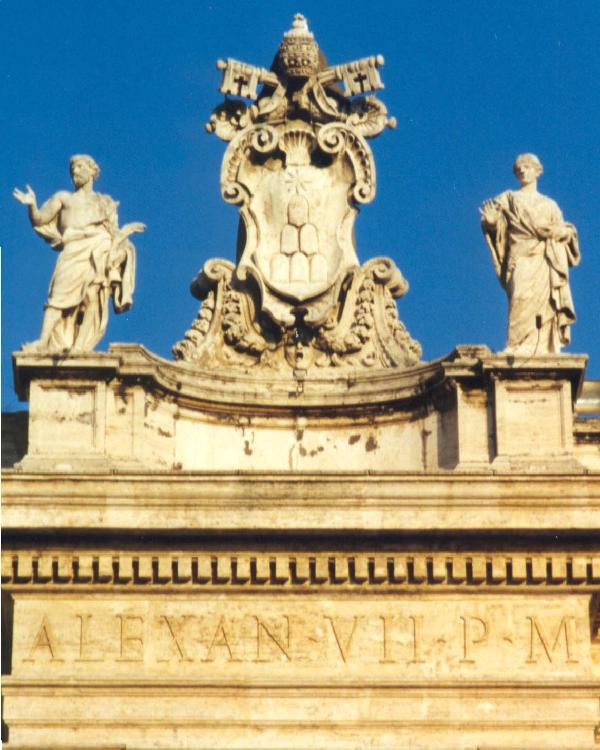

Arms of Alexander VII (1655-67) on the Colonnade of Bernini, Saint Peter.

Arms of Clement XII (1722-40), palazzo della Consulta, Rome.

Arms of Pius VI (1775-99), reverse of a 1780 silver scudo. Courtesy Compagnie Générale de Bourse.

John Paul II, elected in 1978, bore the following arms.

The Holy See, as governing body of the Church, has the following arms, since the 16th century: Gules, two keys in saltire or and argent, interlaced in the rings or, beneath a tiara argent, crowned or. The difference is here that the tiara is a charge, not a timbre.

Flag of the Papacy

From: esn4616@ACFcluster.NYU.EDU (Elliot Nesterman)

Prior to the modern 19th century flag, there existed something called the papal banner, which has a very long and confused history. According to Galbreath, Leo III (pope from 795 to 816) gave Charlemagne a banner which is represented in a contemporary mosaic of the Lateran triclinium: "it is a green flag of the gonfalon type with three tails, with numerous gold dots and with 6 disks coloured red, black and gold, which doubtless are meant to represent embroidery." This banner was the vexillum of the Roman militia, not really the papal banner, and in any event disappears from history until the mid-11th c., when popes take the habit of giving specially blessed flags for specific military campaigns; one of which was that of William the conqueror. Parallel with this flag of the gonfalon type we find the persistence of the classical signum, a staff tipped by a cross with a short oblong of red cloth fastened to a transverse bar below. Of the various banners given out in that period (1044, 1059, three around 1065, 1087, 1098, 1106, 1114) nothing is known except from the tapestry of Bayeux. In the tapestry, William the Conqueror (to whom we know from elsewhere that a papal banner was given) is shown with a banner of Argent, a cross or between four objects (cots? crosslets?) sable.

- Donald L. Galbreath: Papal Heraldry. Cambridge, 1930; Heffer and Sons.

- Bruno Heim: Heraldry in the Catholic Church: Its Origins, Customs and Laws. Gerrards Cross: Van Duren, 1978.

- Baron du Roure de Paulin: L'Héraldique Ecclésiastique. Paris, 1911; H. Daragon.