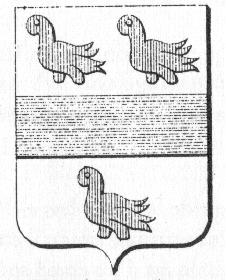

Various martlets: French, late 19th c. (left); English (A. C. Fox-Davies);

French, mid-18th c. (Diderot Encyclopédie plates)

There is some dispute as to what kind of bird it is. In English heraldry, it is a swallow; in French heraldry, it looks very much like a duckling. In German heraldry, it is said to be a lark. It was originally a small blackbird, then became a generic small bird, then a bird without feet and even later without beak, the species of the bird interpreted variously depending on the country.

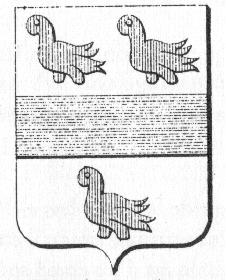

Various martlets: French, late 19th c. (left); English (A. C. Fox-Davies);

French, mid-18th c. (Diderot Encyclopédie plates)

According to Pastoureau: Traité d'Héraldique (2d ed., p. 150-1), the charge makes its first appearance c. 1185 in the arms of Mello in Normandy, and is at first confined to similarly canting arms (Merlot, Merloz, etc). Therefore, it is initially thought of as a small blackbird, called merle in French. From the mid-14th c., however, it appears as a canting device for families named Oisery, Oisy, Loiseau, which indicates that it is now seen as a generic bird rather than any specific species. Its depiction is still quite variable (with or without feet), and in any case it does not lose its beak before the late 15th c. As the Oxford ENglish Dictionary says (s.v. martlet): " It seems possible that the heraldic bird may originally have been intended for a `little blackbird', represented without feet by accident or caprice, or with symbolical intention." Most likely, the need to save space led artists to skip the feet of the small birds that were often used as filler or bordure elements (the orle of martlets is common in early heraldry). Also, in the late 15th c.,, some confusion or competition arises with the canette or duckling, and modern French heraldic textbooks state that a martlet is a duckling without beak and feet.

The evolution in England was different, leading to a swallow. The reason is undoubtedly folk etymology. The Oxford English Dictionary continues: "The English heralds of the 16th c. or earlier identified the bird so depicted with the `martlet' or swift, which has short legs, whence its mod. specific name apus = Gr. apous footless. It is noteworthy that the `martlets' (so called in the 16th c.) in the pretended arms of Edward the Confessor were at an early period portrayed with feet. The anglicized form of merlete, marlet, does not occur in heraldic use, but appears in several 16th c. instances with the sense of martlet, i.e. a swift or a martin. According to English heraldic writers, the use of the footless bird as a mark of cadency for younger sons was meant to symbolize their position as having no footing in the ancestral lands." Woodward and Burnett (A Treatise on Heraldry, p. 266) confirm that: "[t]here are early examples of the martlet properly furnished with legs, but about the close of the 13th c. the custom arose by which the bird is represented without feet, and sometimes without a beak." Gerard Brault (Early Blazon, p. 242) says that "The elimination of the feet (and later the beak) in depictions of the martlet may have been purely conventional". He cites examples attesting to the variety of early depcitions: Mathew Paris shows the martlets of John de Bassingbourne without legs, those of Furnival with legs; the sparrow-hawks of Robert Muschet without feet; a 13th c. panel of Edward the Confessor's arms in Westminster abbey shows the martlets as doves (with feet).

The fact is that Latin blazon always uses the same word no matter the country: merula, or blackbird (cf. Gibbon's Introductio ad Latinam Blasonam, 1682, p. 45 for an English example). I think that the French word merlette, in the form of marlet, was confused with the word martlet (which exists independently in English as the name of a swift, derived from "martin") and the charge was interpreted in accordance; aided by the frequently missing feet and the vague notion that swifts never walk on ground because of their short legs.

In the coat of arms of Cadillac,

used by General Motors for the car of that name, are French martlets, i.e.

ducklings.