The French royal arms were Azure a semy-de-lys

or and (from about 1375) Azure three fleurs-de-lys or.

Younger sons of the king were given titles and apanages, and also differenced their arms so as to distinguish them from the royal arms.

The Genealogy of the French Royal Family

includes the various titles given to junior lines as well as the coats

of arms, when available; more details on titles

and apanages are also available. This page summarizes the practices in the French royal family.

Differencing was performed by all sons of the sovereign. The eldest son and heir apparent sometimes used a bordure (Philippe IV, Jean II, Charles V). In 1349, the last Dauphin (=comte) du Viennois ceded his lands to the king of France on condition that the title be born by the heir apparent only, and that the arms be quarterly France and Dauphiné (or a dolphin azure), a custom which was followed until 1830 (and to this day in the house of Orléans).

The first known mark of difference was the label gules of Philippe, comte de Clermont (†1233). The first systematic attempt at differencing was made for the next generation, among the children of Louis VIII and Blanche de Castille, in the 1240s. The Spanish method of using the Castile castle as mark of difference was used: on a label gules (Robert), on a field gules dimidiating (Alphonse), on a bordure gules (Charles).

This must not have been deemed a success, as Charles himself changed his arms, and the next generation initiated a much simpler system, which was maintained for several centuries.

The system was as follows: The younger sons of the sovereign differenced always by addition of a charge. The charges were:

The use of the label, bordure, bend gules begins in the second half of the 13th century. When these three charges are taken up, there is some hesitation as to the next step: a bordure gules bezanty is used, then a bordure engrailed. The idea of making the mark of difference gobony first appears with the comte d'Évreux around 1300. By the mid-14th century the system is in place.

Within a junior line, whose family name was derived from the main apanage of the founder, various modes of differencing were used, either addition of further charges (three lions argent added to the Bourbon bend, crescent gules added to the Orléans label), a change of tincture (less common: Évreux gobony bend changed to ermine and gules), or quartering with the maternal arms when the mother was an heiress (used by the younger son who inherited the title: Bourbon-Saint-Pol, Bourbon-Vendôme, Bourbon-Enghien).

Initially, the difference was attributed to the son, and he would keep it even if his titles changed, as when Philippe switched from Touraine to Bourgogne in 1363 (which he inherited and quartered with the arms first given to him) and Louis switched from Touraine to Orléans in 1392, retaining the label argent. By the 17th century, however, marks of difference became associated with titles. Thus the label argent became associated with Orléans and the bordure gules with Anjou, and both Gaston and Philippe switched from the bordure to the label when the courtesy title of Anjou was replaced by the apanage of Orléans (1626, 1660). (Note, however, that Charles kept his bordure ingrailed when he became duc d'Alençon et d'Angoulême in 1710). Thus the choice of title determined the choice of the mark of difference, and the simplicity of the older system was lost.

The case of Philippe de France, grandson of Louis XIV is peculiar. He was given the courtesy title of duc d'Anjou but, in 1700, before marrying and receiving an apanage, he became king of Spain. Initially Louis XIV decided that his grandson would bear an escutcheon of France plain en-surtout of the arms of Spain, but a few days later changed his mind and decided to difference the escutcheon with a bordure gules (Dangeau, Journal, 29 nov 1700, 1 Dec 1700; vol. 7 pp. 439, 442 of the 1856 edition).

As said above, the sovereign's eldest son seems to have used a bordure

argent; then, after 1349, he always quartered France with Dauphiné.

If he happened to receive a sovereign title as well, he would grand-quarter

(Brittany in 1532, 1539, Scotland in 1558). In the Middle Ages kings rarely

had grandsons in their lifetime, but this became frequent in the 16th and

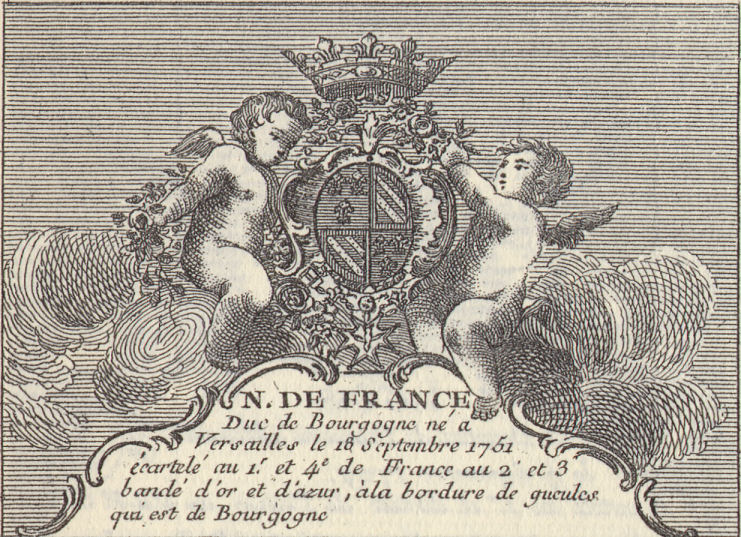

17th c. The king's eldest grandson was duke of Burgundy (1682, 1751) and

quartered France and Burgundy, just as the Dauphin quartered France and Dauphiné.

The eldest great-grandson (1707) was duke of Brittany and quartered France

and Brittany.

Unfortunately, in the 1750s this habit of quartering France with the

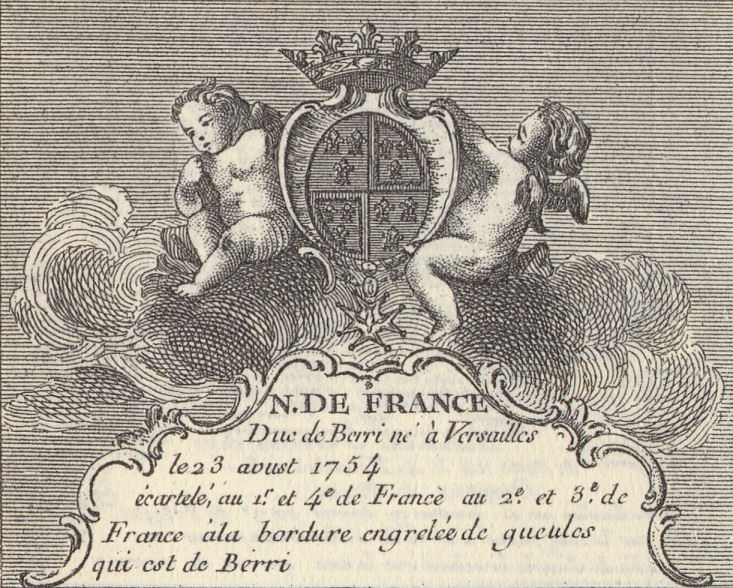

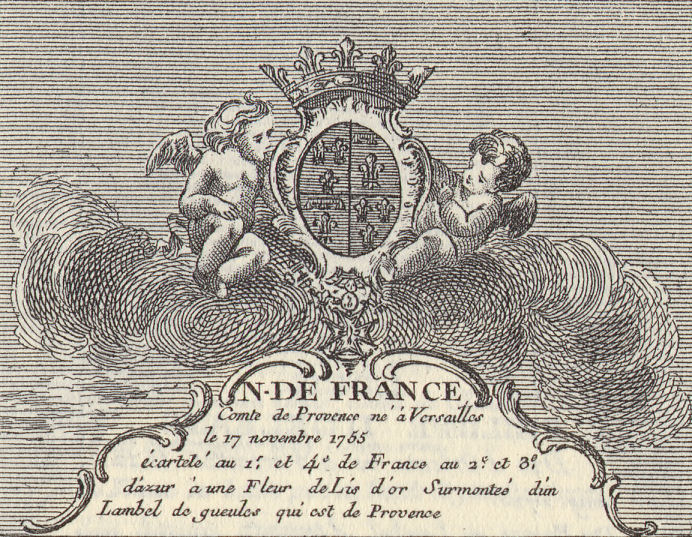

arms of a title, which made sense for eldest sons of eldest sons, was extended to the

younger brothers (duc de Berry, comte de Provence, comte d'Artois), who

should have received marks of difference instead. Since these titles were

all former apanages, their arms were differenced versions of France. The

result was France quartered with differenced France, which was rather unseemly.

In the end, heraldic good sense prevailed, and these quartered arms were replaced by 1771 at the latest with differenced arms: a bordure indented for Provence, and in 1773 by a bordure embattled for Artois (but note that Louis XVI's second son quartered France and Normandie until he became Dauphin in 1789).

The following is the text of a note by Chérin, accompanying a

memorandum on marks of difference in the French royal family, dated

1773 (Source: Archives nationales, O/1/281, n. 91).

Monseigneur

Monseigneur j’ai l’honeur de vous envoyer un mémoire sur les brisures des armes des Princes puisnés de la maison royale depuis plus de 500 ans. Les brisures sont au nombre de 6 sçavoir le lambel, la bordure simple, la bande, la bordure engreslée, la bordure componée et la bordure chargée de besans. Le lambel est attribué à la branche d’Orléans, la bordure simple au roy d’Espagne, la bande à la maison de Condé, et la bordure engreslée à Monseigneur le comte de Provence. Il ne reste que la bordure componée et la bordure chargée de besans. Celle-cy ne paroit pas convenir à monseigneur le comte d’Artois, n’ayant été portee que par Charles comte de Valois petit-fils de France ; mais ne après la mort du roy Philippe le Hardy son aieul. La première semble plus convenable mais au cas qu’il y ait de l’inconvénient à la prendre à cause qu’elle se retrouve dans les quartiers de la maison d’Autriche on peut lui préférer une bordure crénelée de gueules couleur usitée depuis longtemps pour la brisure des princes puisnés de l’auguste maison de France.

Je joins à ce mémoire, monseigneur, des desseins [sic] de ces deux écussons. Lorsque vous aurez opté je vous demanderai vos ordres pour les ornements extérieurs. Je suis avec le plus profond respect, monseigneur, votre très humble et très obéissant serviteur

Cherin

In general, the junior branches such as Condé, Conti, Orléans seemed to practice differencing fairly systematically, by adding charges to the main difference (label, bend couped). But all of Henri IV's as well as Louis XIV's illegitimate sons initially had the same arms (although the Vendômes managed to hijack the arms of Bourbon-Vendôme for themselves).

Daughters did not difference. The daughters of the sovereign all bore France on a lozenge with a princely crown. Daughters of a dauphin bore France quartered with Dauphiné, the arms of their father, until such time as he became sovereign himself. There is a case of the eldest daughter of Louis XV bearing a Dauphin's arms on a lozenge until the birth of Louis XV's son, but I do not know what practice this corresponds to.